Long before elaborate exhibitions of artworks inspired by “miniature” painting became the ‘in’ thing, Waswo X. Waswo and his small team of collaborators broke into the art scene, reframing the idea and visual power of the “miniature” in a contemporary context. Now, almost two decades down the road, their language has evolved and become stronger, embracing varied influences, navigating internal and external shifts, and responding with fresh perspectives to the living, transforming world.

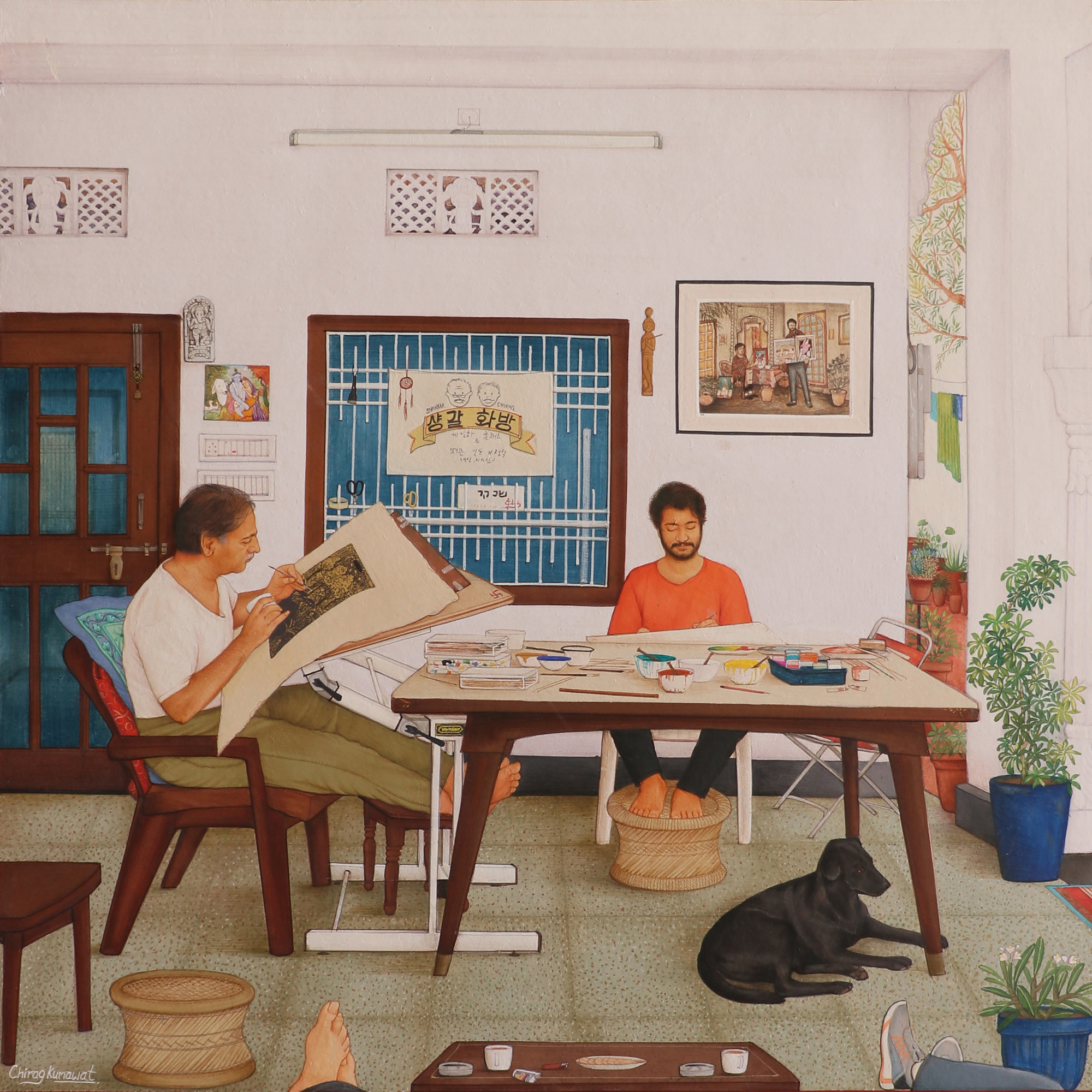

Udaipur, as the place where all this has unfolded, is as important to the “miniatures” as it is to the life of the team. The conferences and discussions that feed the making of the works take place in the homes/working-spaces of each of the current partners – Waswo X. Waswo, Shankar Kumawat and his son Chirag, Dalpat Jeengar and his brother Banti. Map the city of Udaipur across these spaces of conversation and you have a triangle between Moti Magri on the hill overlooking Fateh Sagar Lake, Outside Chandpol near Hanuman Ghat, and Kasaro ki ol in the old city near the Palace, forming the foundation for many beautiful exchanges and birth of ideas.

Waswo recalls his initial reaction to the painting scene when he came to Udaipur many years ago; the act of copy-paste seemed to be deeply ingrained in the artists’ method of visualising, following continuous reproduction of the same subjects and motifs without creative departures or any kind of individual innovation. Driven by tourism, this sort of traditional art market in various Indian cities often conforms to a quick demand and supply chain, almost like a factory. Government initiatives to “uplift” artisans often focus on production and numbers rather than intuitive art-making. Passed on through generations by practice within the karkhana or workshop, there is no school of miniature painting that can safeguard both the historical relevance of the artform and the livelihoods of the practitioners. Then again, the formal Indian art industry is still grappling with the discourse on contemporary indigenous practices and how they fit into the mainstream artistically and economically.

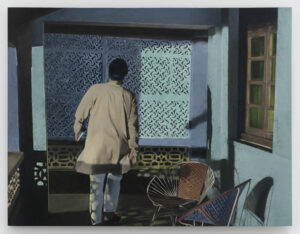

Having explored Indian subjects through photography since the early 2000s, it was within this space that Waswo entered, exploring the language of miniatures and its capacity to tell stories. While encouraging them to break away from rigid pictorial structures, he transformed the artists’ skills by gently leading them in new directions. Two distinct visual forms, interconnected through inspiration and content, came about at this point – the contemporary experimental miniatures and the hand painted photographs, in collaboration with Rakesh Vijayvargiya (R. Vijay) and Rajesh Soni, respectively, with whom the Studio in Rajasthan began (R. Vijay and Rajesh Soni currently pursue independent careers as artists, and are not members of Waswo X. Waswo’s team).

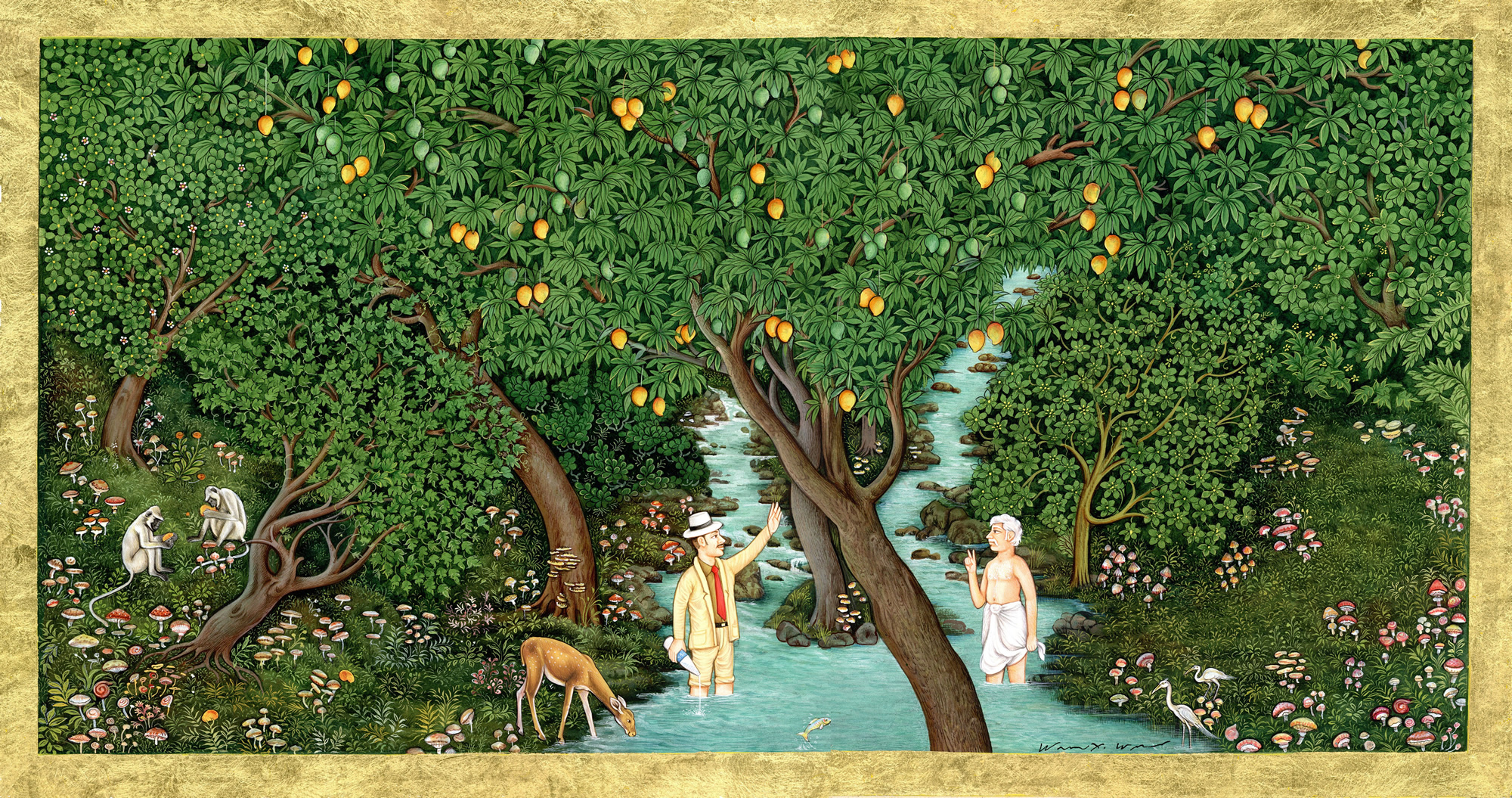

Over the years, the paintings followed the adventures and foibles of the character in the fedora hat, surmised as a stand-in, alter-ego or fictional counterpart of Waswo. The narratives are layered, with complex commentaries combined with mundanity and humour, bringing the personal and the universal together in a deeply poetic manner. All this, set against the dramatic and beautiful landscape of Udaipur.

Teamwork

The paintings may be called miniatures after the visual tradition, but in scale they have grown to large panels, with diptychs, triptychs and suites exploring a variety of themes. Creating the miniatures is a slow, shared process, and while the team prepares intensely for their upcoming exhibition at the end of 2025, the mapped triangle in Udaipur becomes busier, as the ideas have taken physical shape and the works move from studio to studio, from brush to brush, with Waswo’s right-hand-man Ganpat Mali often ferrying the precious cargo around town.

Waswo, or ‘chacha’ as he is fondly known, usually develops the ideas with rough sketches, which are then discussed with the core team – Shankar and Chirag, Dalpat and Banti. With a certain amount of back-and-forth and newer suggestions from the others, the original idea may change shape and direction; sometimes one of the team may come up with a new plan altogether, that is taken forward with enthusiasm. Each artist has a distinct role to play, with the many parts coming together seamlessly in the finished paintings.

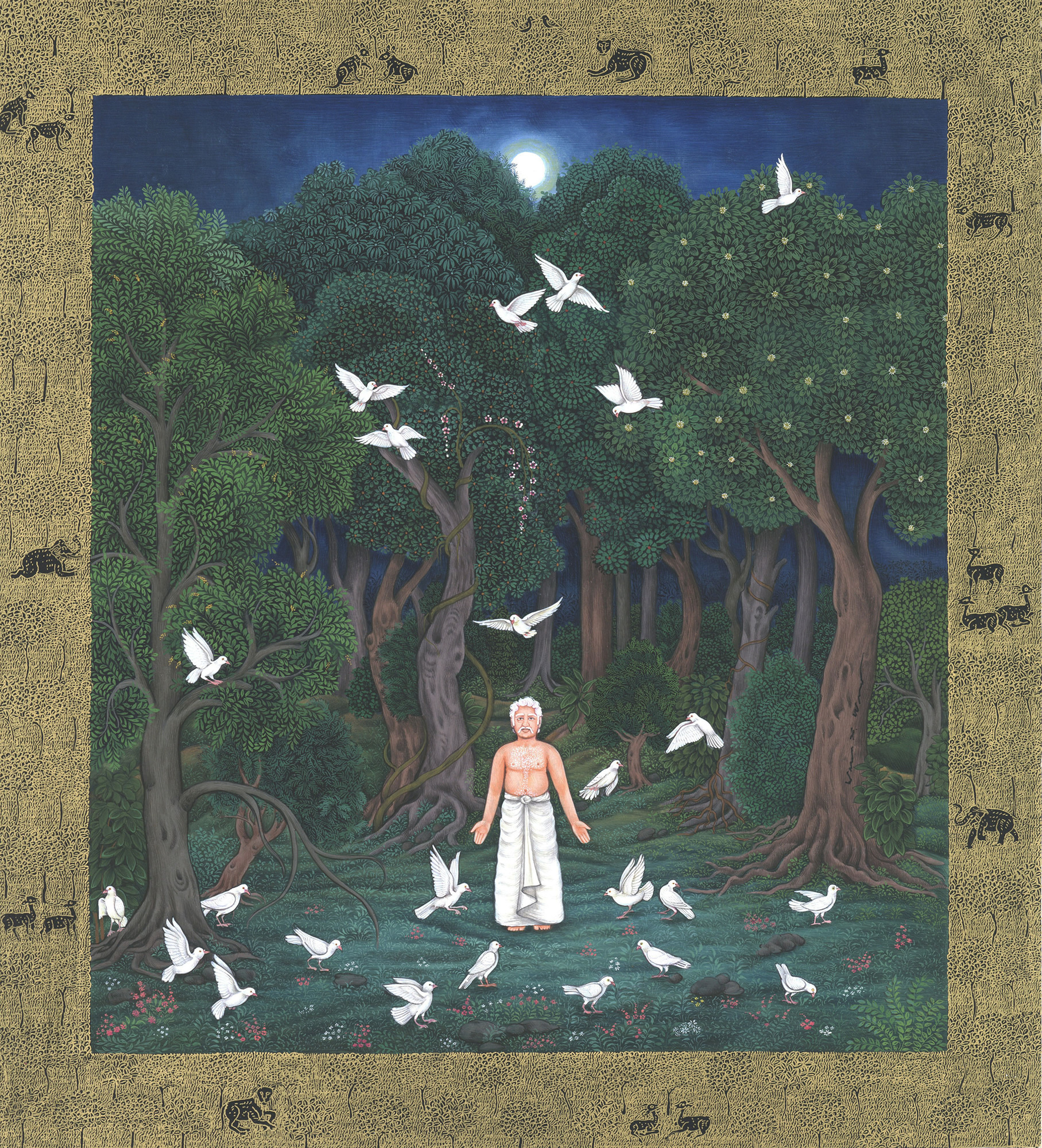

Shankar Kumawat has been a master border-painter for two decades, and considering his meticulous and intricately detailed gold work he also paints large sections of the compositions when required. Once a background is glossy and complete, the artwork is handed over to Dalpat to work on. A miniaturist skilled in painting realistic landscapes, flora and fauna, he builds the world and atmosphere of the scene, along with Banti, who works on elements in the background – mountains, trees, clouds – rather than the foreground. Previously, the brothers used to paint large backdrops for the photographs that Waswo made in his Varda studio, a task now handled by another artist. The final station of the painting’s journey is with Chirag Kumawat, the youngest in the team, who brings in the figures, the quintessential protagonists of the narrative. He enjoys painting naturalistic expressions and gestures that command attention in the richly constructed sceneries, also adding (scientifically accurate) forms of birds and other creatures inhabiting the land and sky. There is a cohesive wholeness in the imagery that reflects the unity, balance and mutual respect within the group.

Fitting in

Once viewed with doubt, the genre of contemporary “miniature reinterpretations” has now garnered a strong following among (select) galleries and collectors, allowing space for multiple experimental inroads into the form and aesthetics of the practice. Waswo’s own contested outsider-insider status, brought satirically into the public eye through his ‘Confessions of an Evil Orientalist’ series, has moved into the background. While the story of the foreigner in India continues to guide the work – the narrative focus has moved into wider contexts, chronicling contemporary mythologies, and often referring to and including visual histories that offer space for research and debate. Looked at in retrospect, the intertwined presence of both the miniatures and the photographs from Waswo’s studio provide a complex narrative, one that curators and writers have sometimes found hard to place.

“Miniatures” have been discussed in several important volumes including most recently ‘Alchemy: Contemporary Indian Painting and Miniature Traditions, Geeti Sen (Mapin Publishers, 2024), ‘Karkhana: A Studio in Rajasthan’, (Mapin, 2022) and an earlier book about the collaborative practice, The Artful Life of R. Vijay, written by Annapurna Garimella with a preface by Kavita Singh (Serindia Contemporary, 2015).

His upcoming exhibition titled ‘The Darkness and the Star’ is an homage to Waswo’s partner of 35 years, Thomas Livieri affectionately called ‘Kaka’, who passed on in late 2024. It is a poetic and emotional tribute coming together in a stellar collection of artworks, with not only paintings but also sculpture and moving image. The theme of death, afterlife and spirituality seems to continue the discussions brought into their previous showcase at Gallery Isa in Mumbai ‘Heaven and that other Place”, 2024.

Waswo X. Waswo, photographer, artist and curator, has also been a collector of Indian printmaking as well as traditional miniatures – the majority of which he has now donated to premiere museums in India and abroad. Sitting in his home-office in Moti Magri, he feels embraced, accepted and happy with the work he is creating along with his team. Over the years he has mastered a choice few phrases (and important cuss words) in Hindi, and as he dreams up his next assignment, his one complaint is about the apartment getting overrun with artworks and frames. But then, that’s what happens when they are always working…