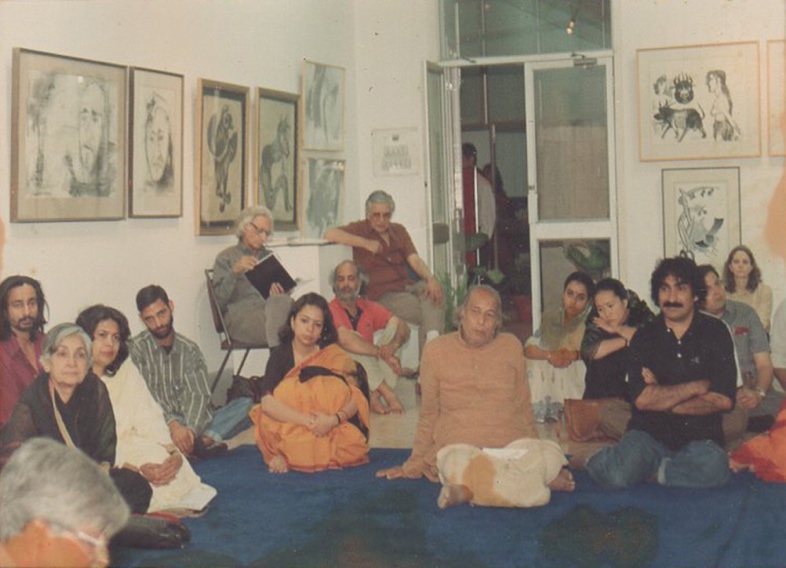

The journey of Art in its modern, contemporary avatar in the subcontinent is not tied to the emergence and spread of institutions alone. This story is as much about relationships, improvisations, and friendships, as it is about exhibitions and collections. In fact, the history of galleries in India can be thought of as an “invisible” network—a web of ties between entrepreneurs and patrons, artists and critics, collectors and institutions. These ties may not always be visible, but they shape how art is made, circulated, and remembered.

The genealogy of modern Indian art galleries can be traced to humble printing and framing businesses. One of the pioneers was Dhoomimal Art Gallery, whose roots lay in Dhoomimal Dharamdas, a stationery and printing business in Old Delhi’s Chawri Bazaar. In 1936, Ram Babu, a member of the family, relocated the framing business to Connaught Place, the newly built commercial hub of New Delhi. The intermediate floor above the shop was converted into a modest exhibition space. It was here, almost quietly, that Delhi’s modern art scene began to take shape.

A similar story unfolded in Bombay. Kekoo Gandhy, who established Chemould Frames, a frame manufacturing business in 1941, doubled as a patron and connector in the city’s art world. Alongside him, the Austrian-born painter, critic, and dealer Walter Langhammer, who had escaped Nazi Germany in the 1930s to come to Bombay in India, subsequently became an influential figure, opening his home to young artists and helping them secure platforms for their work. These early initiatives were modest in scale, but they provided the scaffolding on which larger networks of galleries and collectors would later build their visions.

The decades following Independence saw the state step in to institutionalise art. The Lalit Kala Akademi was established in 1954, followed closely by the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi. The government’s acquisition of ninety-six paintings by Amrita Sher-Gil in 1948—just seven years after her death—formed the NGMA’s founding collection. With these institutions came exhibitions, acquisitions, representation abroad, and public commissions.

Yet the state was never the sole player. Private galleries like Kumar Gallery, opened in 1955 by collector Virender Jain, offered a parallel platform. Moreover, for decades after the British moved India’s capital to Delhi in 1911, Calcutta remained the center of the art world, building on the legacy of the influential Bengal School of Art. For the first time now in the mid-20th century, Delhi and Bombay began to eclipse Calcutta as a nucleus of the Indian art world. These galleries provided not just walls for exhibitions but also crucial financial and moral support to artists struggling in uncertain times. The Progressive Artists’ Group—M. F. Husain, F. N. Souza, Ram Kumar, and Krishen Khanna among them—benefited enormously from these spaces, which allowed them to refine their practice and reach new audiences.

But the relationship between government bodies and private galleries was often uneasy. Artists complained of bureaucratic red tape and restrictive selection processes. The conflict came to a head during the Fourth Indian Triennale in 1978, when leading artists—including Husain, Tyeb Mehta, Bikas Bhattacharjee, and Vivan Sundaram—boycotted the event. With support from private galleries such as Dhoomimal, Kumar, and later Art Heritage, founded by Ebrahim and Roshan Alkazi in the late 1970s, they staged independent exhibitions that asserted the vibrancy of contemporary Indian art outside the shadow of state control. Husain’s Portrait of an Umbrella was one of Art Heritage’s early landmark shows where he explored the everyday object as a motif rich in layered associations. The bold brushwork evoked Husain’s early days as a billboard painter in Bombay. The exhibition was more than a show—it was an act of reclaiming artistic agency from official institutions.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the state’s monopoly over art and culture began to weaken. Private collectors and corporate houses stepped into this space, transforming the art world into a more independent marketplace. Companies such as the Tata Group and ITC Limited had already amassed substantial collections of modern and contemporary art. Now, they sought to display them more prominently. Hotels and corporate offices became sites of exhibition. Tata Consultancy Services and the Taj Group of Hotels hung works by Husain, Souza, and Mehta in their lobbies and boardrooms. ITC’s luxury hotels integrated art directly into their architecture. A striking example is Krishen Khanna’s mural The Great Procession, commissioned for ITC Maurya in Delhi. Initiated in 1979 and completed in 1983, the work combined imagery of India’s Mauryan past with scenes of skyscrapers, city streets, and natural landscapes, presenting a kaleidoscopic vision of a modernising India. This moment marked a decisive shift: art was no longer confined to galleries or museums but began to occupy everyday public and semi-public spaces, subtly altering how audiences encountered it.

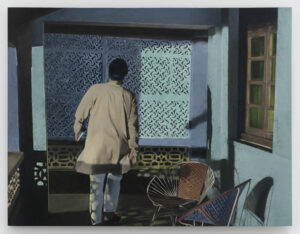

By the 1980s, Delhi had become a hive of artistic activity. Journalist Madhu Jain noted that the city hosted no fewer than seventeen galleries by this time. In October 1989 alone, six galleries opened, including the Centre for Contemporary Arts, Habiart (a collaboration between HUDCO and Rekha Mody), Display Gallery (run by Hema Bawa), Dolly Narang’s Village Gallery in Hauz Khas, and Gallery Espace, founded by Renu Modi and Rasha Siddiqui. The inaugural show at Gallery Espace featured autobiographical sketches by Husain, recalling his early fascination with calligraphy, and his childhood days until 14, when he lived in Indore.

Modi, then a newcomer to the art world, leaned heavily on the support of artists like Husain, Tyeb Mehta, and J. Swaminathan, who guided her through logistics, networks, and introductions. Artists’ bonds with the Modi family extended beyond exhibitions. In the mid-1980s, Husain designed their Delhi residence, envisioning a Keerti Stambh clad in bronze and inscribed with verses from the Bhagavad Gita at its heart. In a poetic note titled Genesis of a “House”, he described the building as a living artwork, comparing reflections on its glass panels to scenes from a Manet painting. It was during those days that Husain had encouraged Modi to set up an art gallery, which became Gallery Espace. The logo done by Husain featured a galloping horse, a recurring symbol in his work, representing his raw energy and vitality for the arts. Art galleries were thus formed not merely as impersonal spaces but deeply embedded in personal relationships.

Another transformation came with the rise of auctions. In 1989, the Times of India and Sotheby’s organized the Timeless Art auction in Mumbai. Widely regarded as a milestone, it marked the birth of India’s modern auction market. Around the same time, Delhi saw the Artist Alert Auction, organized by Sahmat in memory of playwright and activist Safdar Hashmi, who had been killed earlier that year. Both events demonstrated how art could straddle market value and political urgency. At Timeless Art, Husain’s canvas Freedom: A Tribute to Hashmi fetched over ten lakh rupees—a first for the artist—signaling the soaring financial value of contemporary Indian art. From then on, Sotheby’s and Christie’s would regularly feature Indian works, linking local practices to global circuits of capital and taste.

The 1990s were a period of experimentation. At Gallery Espace, Renu Modi and Husain’s shared fascination with the line culminated in Drawing ’94, a landmark exhibition featuring 150 black-and-white drawings by 80 artists. Veterans like Souza, Raza, Gujral, Padamsee, and Khanna were shown alongside younger figures such as Bhupen Khakhar, G. M. Sheikh, and Arpita Singh. Curator Prayag Shukla remarked that many young artists tended to neglect drawing after early successes. The exhibition was a call to re-examine the foundations of practice.

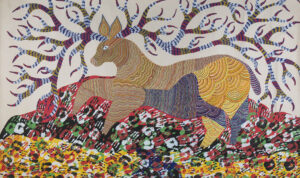

Three years later, Espace partnered with NGMA for The Self and the World (1997), curated by Gayatri Sinha. Bringing together fifteen artists including Amrita Sher-Gil, Nasreen Mohamedi, Anjolie Ela Menon, Nilima Sheikh, the show consolidated for the first time a historiography of ‘women’ artists in modern Indian art. “Until then, it was all scattered,” Modi recalls in a conversation. This intervention was followed in 1999 by Khorshed and Kekoo Gandhy’s exhibition of Sohrai and Kohvar paintings by adivasi women from Hazaribagh, presented in collaboration with the Tribal Women Artists’ Cooperative founded by Bulu Imam. By spotlighting indigenous women artists at a time when they were protesting against the rampant mining industry in Jharkhand, the show aimed to expand the very definition of what counted as “contemporary.”

In the new millennium, galleries have come to embrace new roles. The Vadhera Art Gallery, founded in 1987, established the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art in 2007 as a non-profit platform for grants, residencies, and international exchanges. In 2010, Bhavna Kakar established Latitude 28 in Delhi, extending her engagement with contemporary art that had begun a year earlier with the launch of TAKE on Art. Published biannually since 2009, the magazine responded to a perceived lack of printed discourse on contemporary art in India to create a space for documentation, critique, and expanded conversation around artistic practices. Financially, the art market has boomed. From less than 10 million US dollars in the 1990s, it is estimated today to be over 400 million dollars. A new generation of younger collectors has emerged, with growth rates of more than 25 percent among first-time buyers. “Curation” has become a buzzword, shaping gallery programming and reflecting both sophistication of art as an industry and its evolving aesthetic engagement.

Despite the market’s dramatic expansion, some things appear to have been lost. Looking back on her early years, Renu Modi recalls the “human quotient” that underpinned the art world. Recalling her last phone conversation with Husain just before he passed away in London in 2011, Modi remembers Husain’s description of himself as an artist “जो थोड़ी-बहुत लकीरें खींच

लेता है”—one who knows just enough to draw a few lines. Those few lines connect not just artists and their work but also the invisible relationships with collectors and patrons that make and shape this industry. Yet few accounts have tried to trace this network in a comprehensive manner.

As the art world becomes more ‘sophisticated’, the challenge is to remember that its foundations were laid not in “readymade institutions” or big auctions alone, but in a network of unique personal ties and varied circumstances—gallerists who started humbly, artists who shared homes, collectors who doubled as confidants. To visibilise this “invisible” network is not merely to historicise modern and contemporary art in India. It is to recognise that art’s survival has always depended on more than markets, museums and disciplines. It has depended on relationships—lines drawn and redrawn between artists, collectors, and galleries, each sustaining the other in a fragile but enduring balance.