When I met her online, Paula Sengupta was in her study, winding down from her busy stint at a printmaking residency. It was a Thursday morning in the month of September, and the only time I could catch Paula before she became swamped with academic duties and other commitments. As the Head of the ‘Graphics- Printmaking’ Department at Rabindra Bharti University in Calcutta, Paula was busy preparing for the new academic session. She was zealous from the two-month-long residency, evidently overjoyed to have been doing what she described as her ‘first love’– the art of printmaking.

Although Paula dabbles with a variety of mediums and techniques, printmaking is her instinctive choice, especially when she is at the conception stage of an artwork, installation, or exhibition. She brainstorms her way into bigger projects through drawings, etchings, and collages.

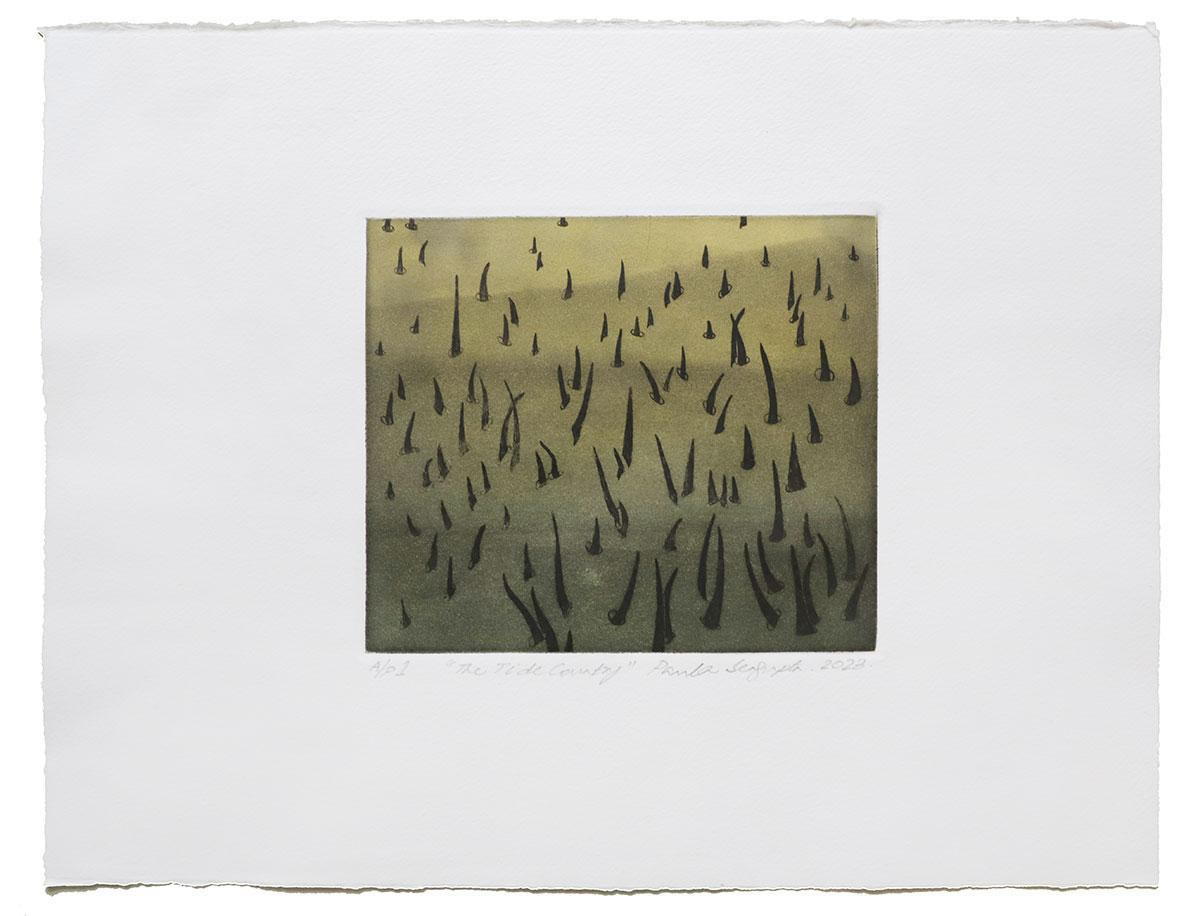

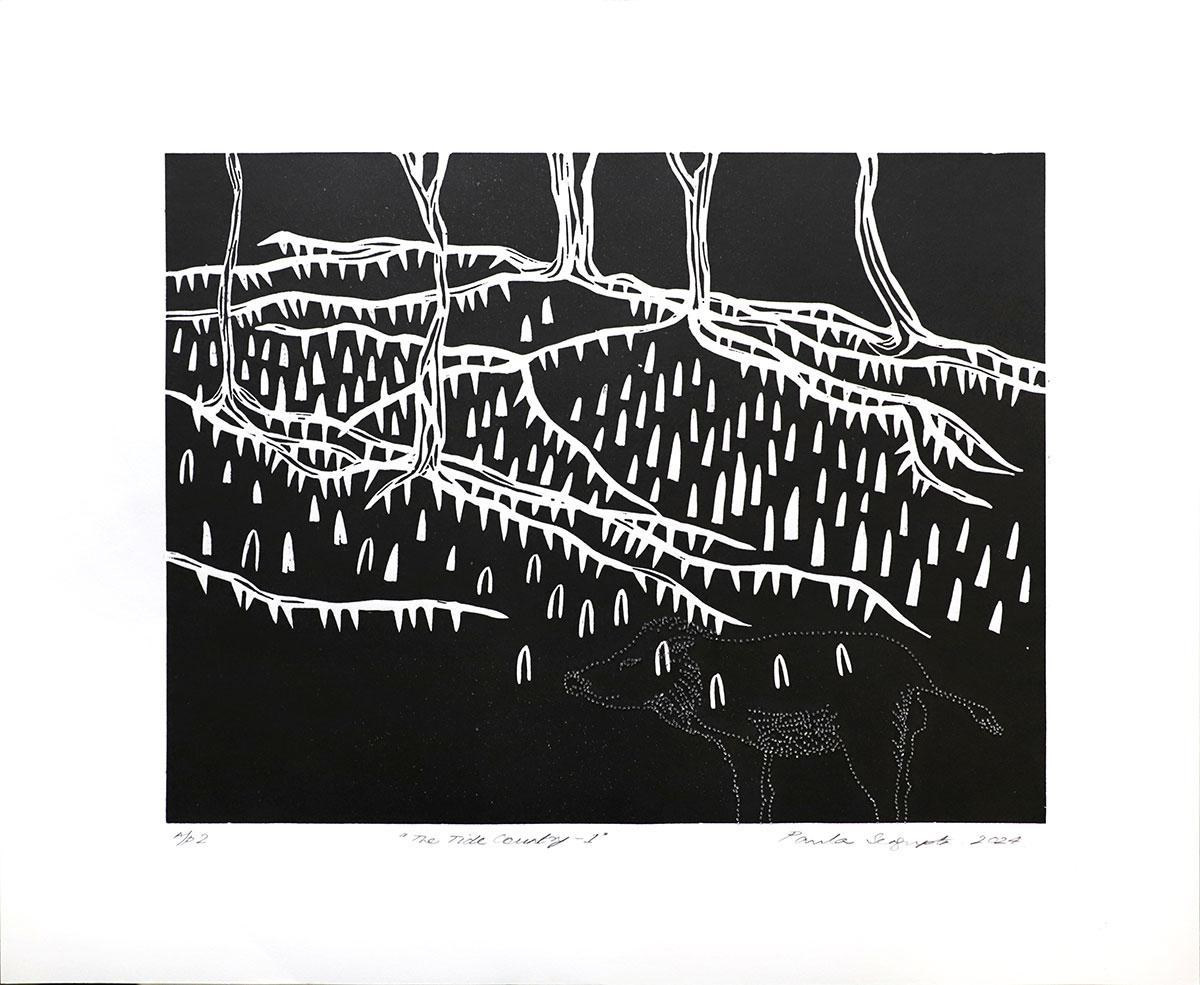

The Tide Country (2023)

Etching and Aquatint on Paper

During the pandemic, Paula made a visit to the Indian Botanical Garden (hereafter, The Botanics) in the industrial town of Howrah. It was here that she learned the story of the last king of India, who meticulously maintained an assortment of exotic wildlife. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (1822- 1887) was stripped of his sovereignty when the British East India Company annexed his beloved kingdom of Awadh in 1856. To add insult to injury, the Company auctioned off his prized possession– his vast menagerie of animals and birds. He set sail to Calcutta, where he would, in time, rebuild his collection.

In the eerie silence afforded by a COVID-stricken world, Paula Sengupta apprehended the tale of two tigers who escaped from the Nawab’s enclosure, with one of them crossing the Hooghly River to reach the Botanics. “ You know, swimming the Hooghly is no joke”, she says with a hint of playfulness.

Besides the story of the unruly tigers which escaped the captivity of their master, the Botanics also directed Paula’s attention to The Great Banyan Tree, which, according to the artist, has been a keeper of time for centuries– a witness to the release of the tigers once, and now, to the humdrum of industrial development. Paula considers the tree to be a ‘signifier’.

“The Great Banyan had to be amputated because it had become diseased. Yet, the tree continued to survive through its proper roots. So, the authorities at the botanics have tried twice to fence the tree in. But the attempts failed because the tree had exceeded the fence. It drops roots outside the fence. And it’s moving towards the river…”, explains the artist.

The escape of the tigers and the defiance of the banyan tree both encapsulate a story of nature’s fundamental quality of being irreverent to human hubris. Paula’s practice embodies this irreverence, this resistance. At a time when artists are moved to a state of urgency at the narrative of impending climate catastrophe, Paula remains unfazed. Her art, instead, imagines a world where the Anthropos has never really been at the proscenium of the linear play that starts with evolution and ends with the erasure of humankind.

1. The history of the city is hinged on the river

Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was an Awadhi Royal considered to be the ‘Last King’ of India. He was exiled from his homeland in Lucknow in 1856. Heartbroken, he spent the rest of his life cloistered within a palace of mud that rose from the swampy soil of the Bengal delta, Matiya Burj. In an artwork from the eponymous series, Matiya Burj is embroidered into a square piece of Muslin cloth that forms the centrepiece of the compilation. The tower, bordered by the wilderness of pneumatophores, stands guarded by the tiger figurines. We see the Nawab’s final fortress– the tower of mud.

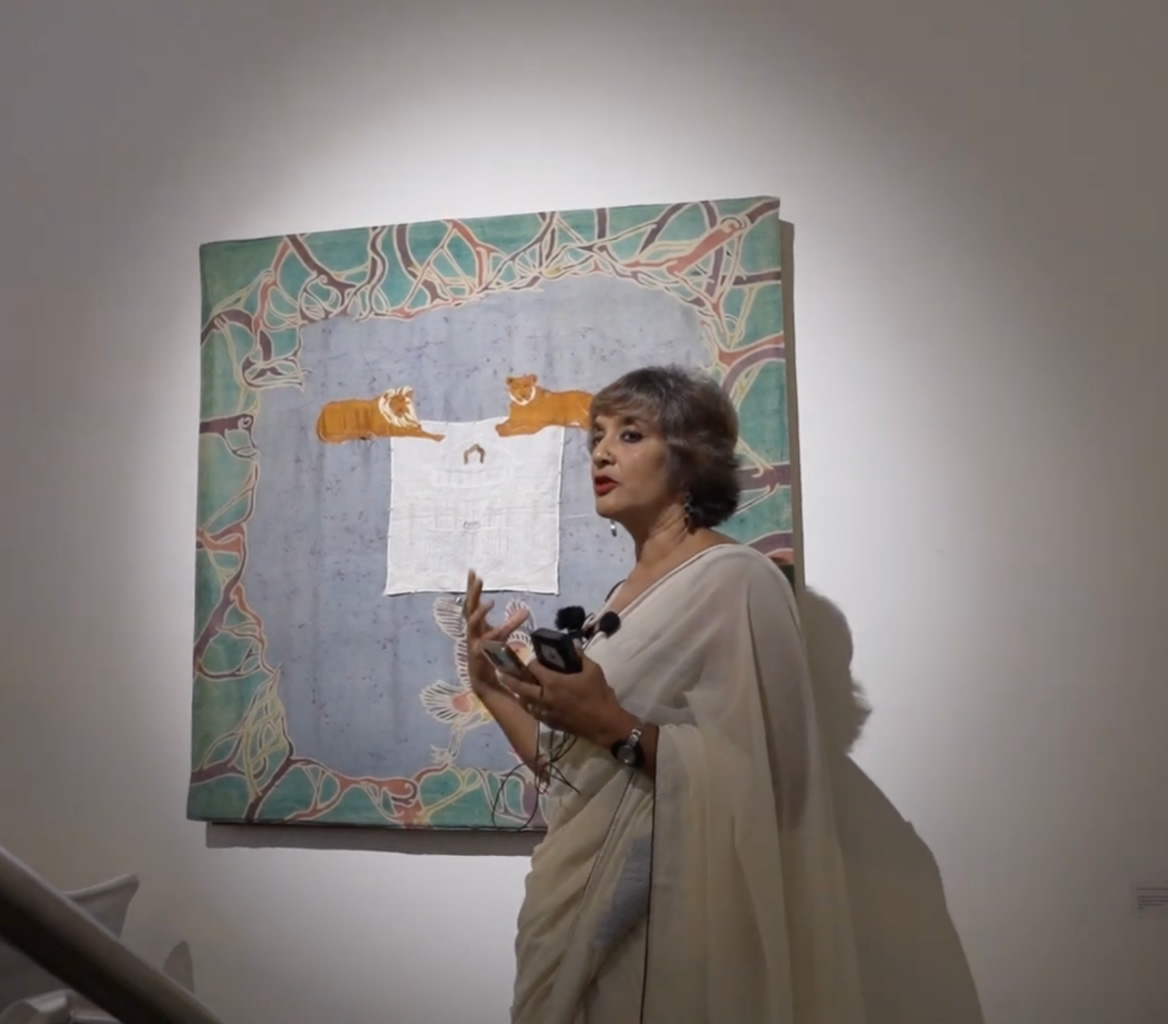

Paula’s practice is a hybrid one – she is an artist, writer, curator and printmaker, whose diverse body of work explores the vibrant, more- than- human entanglements that constitute riverine landscapes. In her Matiya Burj collection, Sengupta vividly captures the amphibious ecology of the delta.

“What interested me about Wajid Ali was his menagerie”, explains Paula. The Nawab deposed from Lunckow, passionately continued to curate an extensive menagerie of animals. This activity was perhaps his only way to sustain affinity to the lineage from which he was sutured by geography. It was a convention among the royals of Lucknow to carry out beautification projects. As the British rule tightened its leash on the sovereigns of Awadh and undermined their authority, the Nawabs became more indulgent in their pursuits of leisure– ornate walled gardens, architectural enclaves, summer houses and other decadent projects of landscape modification housed the fluvial sensuality and hedonism of the last heirs of Awadh.

In 1856, after the complete annexation of Lucknow city by the British, Wajid Ali Shah relocated to Calcutta, where he would spend the next three decades of his life. Upon arriving at the Bichali Ghat, the Nawab occupied himself with rebuilding the menagerie from scratch. The menagerie at the Garden Reach Palace was “stocked” with serpents and Bengal Tigers, to name a few eclectic inhabitants of the Nawab’s court.

‘The king himself was a prisoner of destiny; there was no escape for him, ’ says Paula, contrasting his dire state of imprisonment with the tigers’ escape.

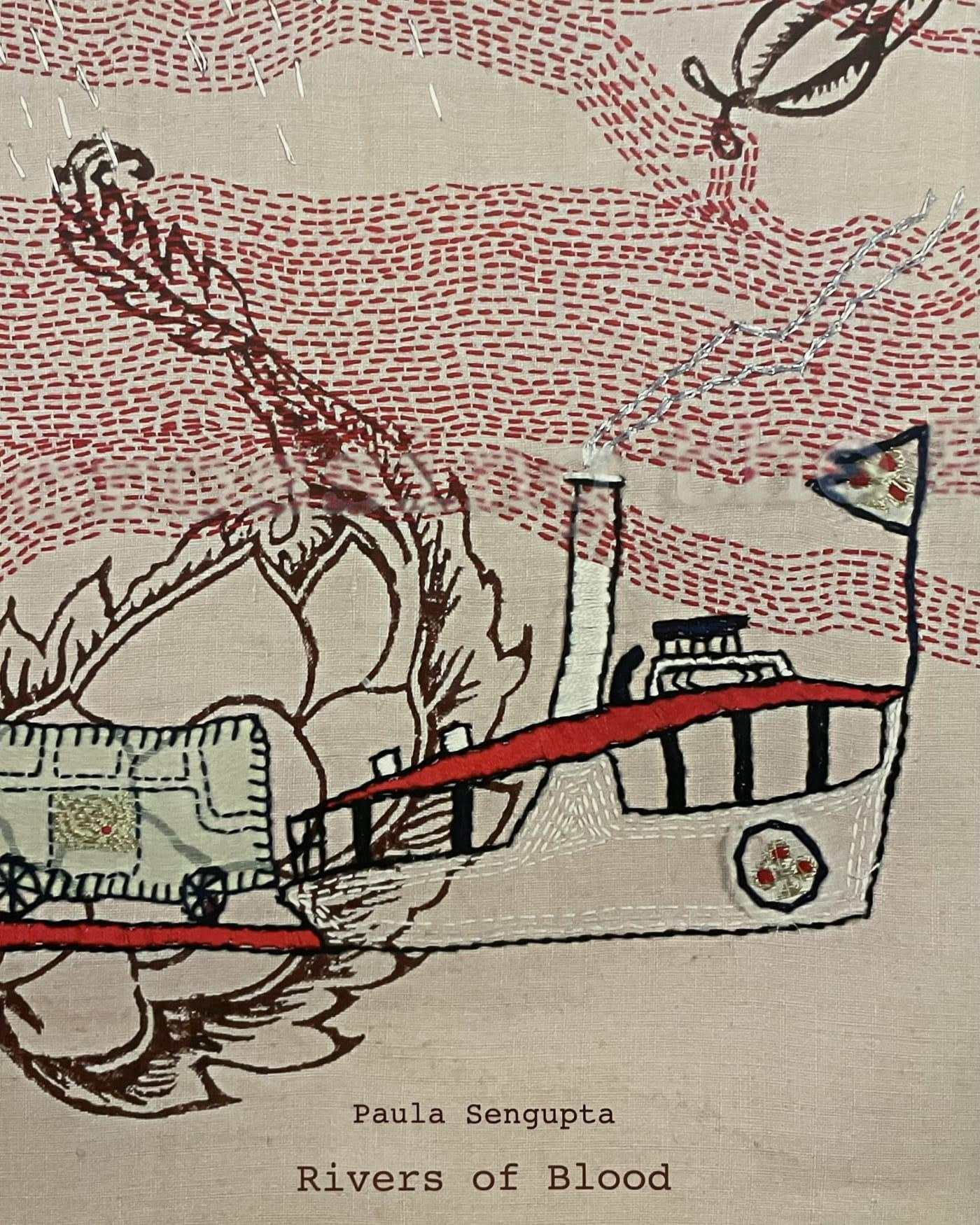

In her work, ‘A river of unrest… a delta of dreams’, Sengupta recapitulates the atmosphere into which the Nawab arrives in Calcutta. Wajid Ali Shah’s journey of exile which began at the Gomti river in present-day Uttar Pradesh, culminated at the shore of Bichali Ghat in Calcutta’s Matiyaburj. In the panel above, Sengupta fabricates the pallu of a red Bengal Tangail Saree the artist inherited from her mother to render alive the image of Wajid Ali’s Mayurpankhi vessel drifting afloat the delta.

Using a variety of deliberate mediums and techniques, Sengupta relies on an approach of layering, by which she adds a profound depth to whatever she creates: “Found textiles have histories embedded onto them. What I am doing here is layering my own history, leaving my own imprint upon the textile”. Like the saree fabric that is the artist’s heirloom, the traditional techniques of batik and shibori dyeing also transform into a kind of inheritance in her hands. Paula’s canvas becomes a kind of palimpsest, sedimented with narratives which are both biographical and historical.

Traditions tend to exert a disproportionate weight upon the people bearing them. As textile art was perceived as the preserve of female artists, it also risked being undervalued. An artist coming of age in the 1980s, Paula found it imperative to hold on to the rich tradition of textile art in the subcontinent, without being pigeonholed into the restrictive category of the ‘woman artist’. “ I think I represent a generation of artists, or I hail from a generation of artists who had to confront a lot of rigidity in Indian art, when we started in the 80s.. And essentially, you know, a print maker was a print maker, a sculptor was a sculptor, and a painter was a painter”, comments Paula.

Paula remarks that textiles possess great mobility when compared to other materials. She says, “ I like to think that these textile works may someday travel with somebody somewhere, and be adorned by them once again”.

Paula’s inclination for textile work emerged organically from her experimentation. Implicit in her flexibility to work with various media and her dynamism, was the resistance against gendered artistic labour. In the case of the eight-panelled ‘A river of unrest… a delta of dreams’, Sengupta uses silk as the base fabric. The bright red Mayurpankhi boat was made from the loose end or pallu of her mother’s saree.

“ It was only when the saree began to fall apart that I decided to recycle it into this work. For some time, I stitched the piece to another fabric and continued to don the saree. But the pallu started to disintegrate as well. So, I repurposed it for my work. Now, it feels like a little piece of my mother and me have been woven into the artwork… it continues life in a different avatar, and you know, it interacts with other elements in the piece.”

2. An Overwhelming Vastness

Paula was captivated by art formats that could sew together “continuous narratives”. The frescoes on the walls of various monasteries in the Himalayas and Trans-Himalayas are an enduring source of inspiration for her. A visit to Bangladesh ignited her interest in textile arts. It was here that she learned more about nakshi kantha, a popular quilting tradition practised and perfected by Bengali women. A form of hand embroidery, kantha was produced by layering fraying sarees and old dhotis together, to eventually create a moving canvas of patterns and semiotic elements that represented sacred texts, lore or banalities of domestic life.

Paula understands kantha as a “running narrative field”. Her decision to pursue it in her praxis was also a way of staking a claim to her maternal lineage. Paula’s grandmother hailed from a province in Bangladesh where kantha making was popular. The artist was taught to weave Kantha by her mother.

“Were I born in your generation, I could have been a Kantha artist’ ” – Paula recounts her mother’s words as she trained her to become adept at the artisanal form.

In 2010, Paula released her first textile art project titled ‘River of Blood’.

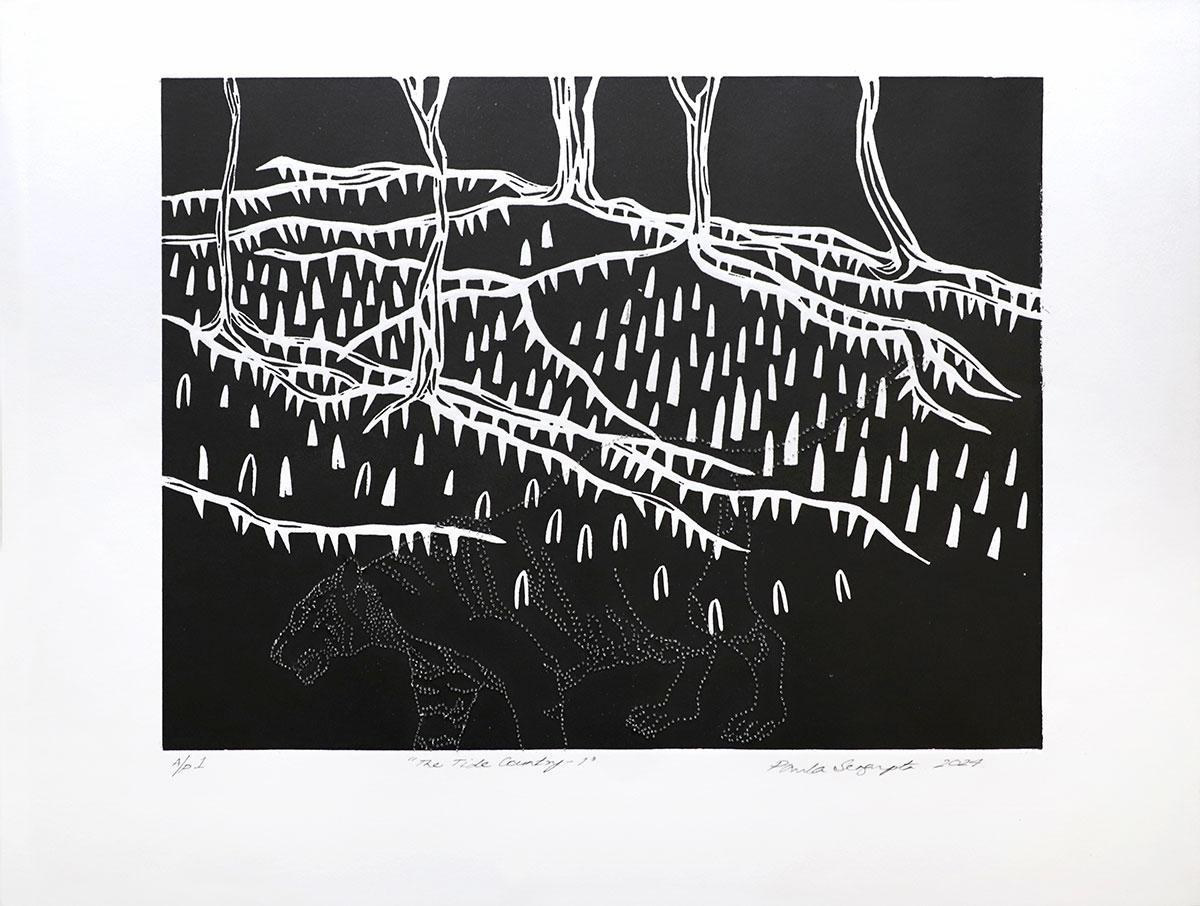

In Paula’s extended body of work, the Nawab’s tale has extended beyond the eight panels of the ‘river of unrest…’. The story has morphed to contain the force of a multitude of lifeworlds in the delta. After her visit to the Botanics in the middle of the pandemic, Paula’s expeditions have taken her to faraway realms, and sometimes, landscapes that are nearby, yet dense and impenetrable– like the Sunderbans.

When she ventured into the Sundarbans for the first time, which was a two-hour drive from the town, Paula was awed by the proximity of the delta to central Calcutta and intrigued by the fact that this closeness did not really translate into familiarity. “It’s actually so surprising… It’s so close to the city; the city is right at the fringes of the delta. But as soon as you enter the Sunderbans, it feels like another world. I couldn’t help wondering that the vast expanse of waterscape before me was part of the same river which I experienced in Calcutta… in the banks of the settlement”.

As the eye wanders over the chiaroscuro prints, mapping intimacy and distance, ecology and history, it confronts the muted appearance of the animals from Wajid Ali Shah’s pack. The animals continue to lurk behind the blackness of the delta, looking on, as the artworks slip quietly into a collective imaginary.