Philippe Calia (b. 1985, Paris) first arrived in Mumbai in 2011. The photographer’s earliest encounters with the metropolis were on the local train – the view from its compartments shaping his understanding of the urban fabric. Over a decade later, his solo exhibition The Second Law (2025) at Tarq, Mumbai brought together “years of observations of the city’s visual grammar”: photographs, ‘happenings’, and writings. This narrative profile explores the relationship between photographic practice and urban life, asking what it means to create a portrait of the city.

Part I: Text

It is 1980. A man stands a thousand feet in the air, at the summit of a monumental building. At this height, the viewer is transformed: “an Icarus flying above these waters, he can ignore the devices of Daedalus in mobile and endless labyrinths far below. His elevation transfigures him into a voyeur. It puts him at a distance. It transforms the bewitching world by which one was ‘possessed’ into a text that lies before one’s eyes”. The man is Michel de Certeau, the city New York.

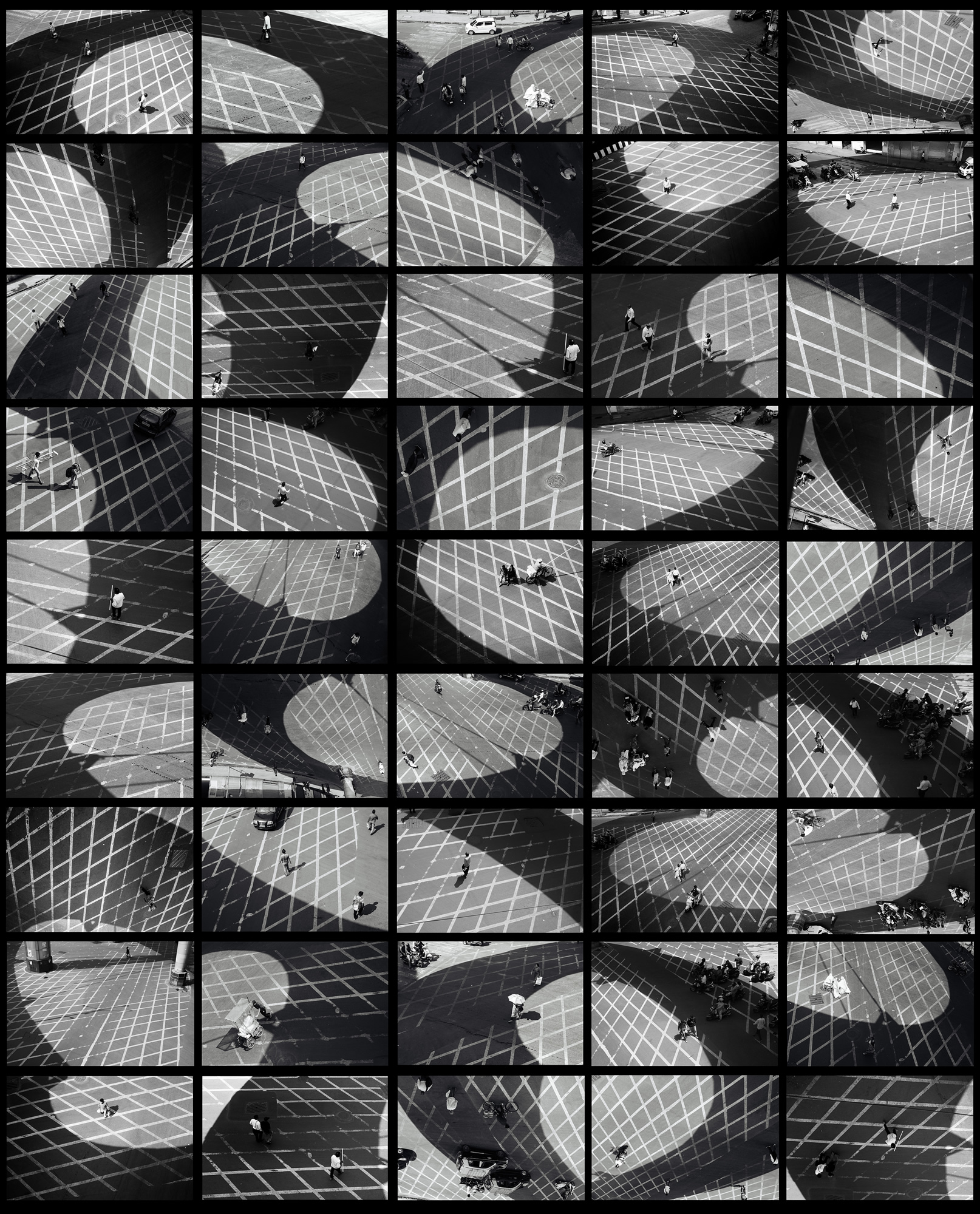

It is 2025. A photographer stands atop a skywalk in south Mumbai, taking pictures of commuters as they traverse a lattice of road markings. With each photograph, he records a new permutation of the labyrinthine city: now a set of pilgrims, now a handyman with a ladder, now a schoolchild on her way home. The photographer is Philippe Calia, the city Mumbai.

Perhaps we can start here. When I saw your work, Philippe, one thing that was apparent was the relationship between photographing the city and reading the city. As an artist who has engaged with writing as methodology, how do you respond to de Certeau’s idea of the city as text?

There’s so much to say about the city. The first thing I can think of is the photograph in The Second Law that says “Vile Parle”. In a very literal sense, there is text in the city, there are words everywhere. I find that these are landmarks that help me forge a relationship with it. What is interesting in Bombay is the coexistence of multiple languages, how sometimes words in a certain language are not necessarily translated, but transcribed. In the process, there is gain, there is loss, there is poetry that happens by accident, like in the case of Vile Parlé, which was spelled with two Ls and became this French statement.

Photography allows you to take note of these words, to possibly have a moment where you bring them together and build sentences. Then there’s the text that emerges in the morphology of urban space. With de Certeau, what struck me most in his approach to the city is the idea that you practice it. The writer Jean-Christophe Bailly has a beautiful book called La Phrase Urbaine, urban sentence. His argument is that you write the city, and that walking is an act of writing. For me, the act of walking was fundamental to this whole project.

What this passage also evokes is the way the city’s morphology makes us see things differently. The density of the city, the way different elements coexist – shop windows, restaurants, street sellers – also creates its own ecosystem, and builds its own language.

Part II: Pattern

It is 1970. A young poet wanders the streets – from bookshop to bar to home – both documentor of the city and participant in its rhythms. Everywhere, there is repetition: “same red bus”,“same stumbling old Parsi woman”,“same winding road”,“same train halting at same stations same minute”. The young poet is Arvind Mehrotra, the city Bombay.

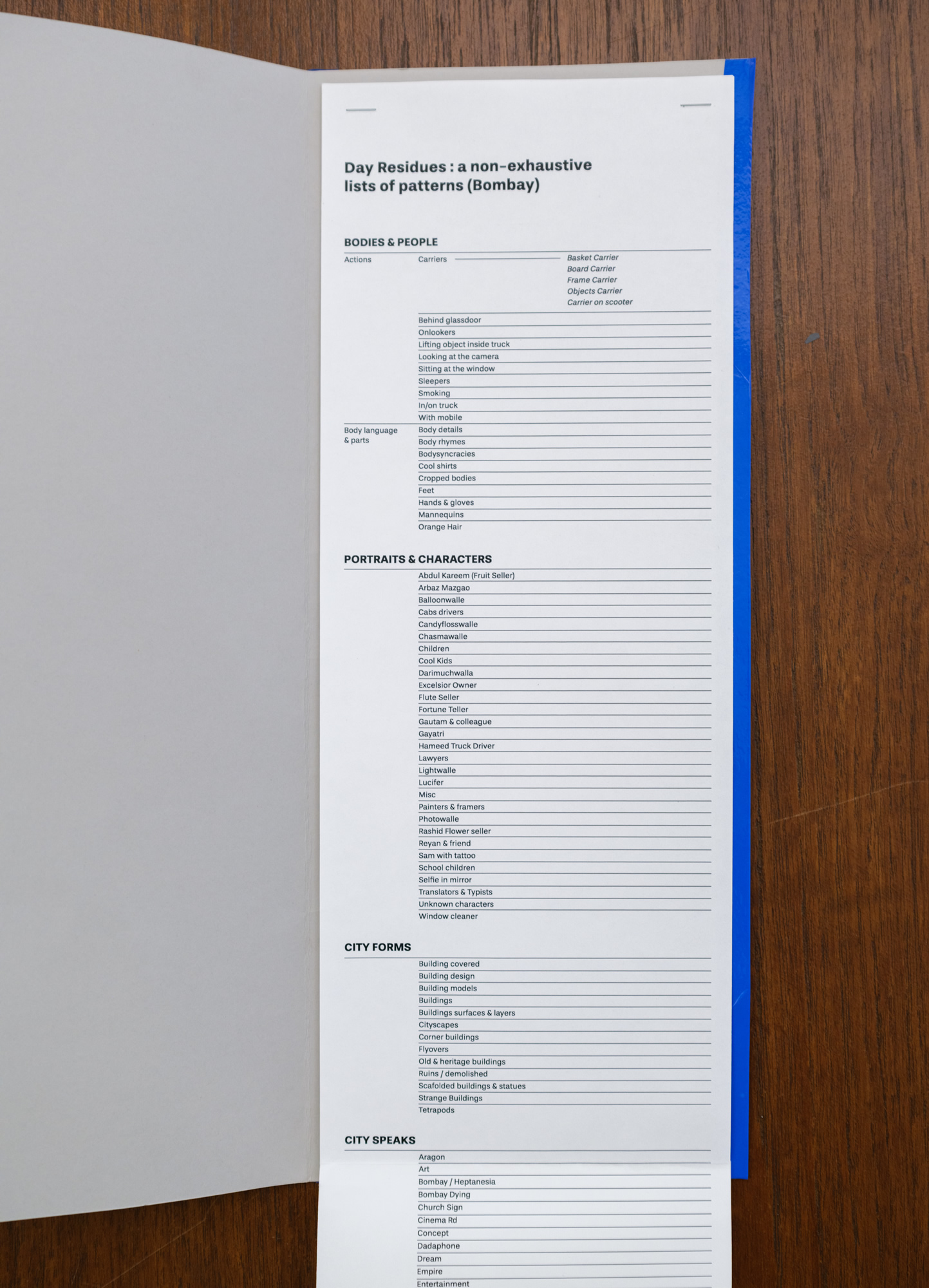

It is 2012. A man begins keeping a list of urban patterns. “Antics/Balloons/Bisleri bottles/Boats” reads one. “Asiatic Library/Banganga Tank/Chor Bazar/Coastal Road” reads another. The list is non-exhaustive. The documentor is Philippe Calia, the city Mumbai.

There are two things that stand out to me in how you articulate your practice: 1) the notion of a morphology of urban space and 2) that of rhythms. Patterns recur in your work. Most obviously with Arun Kolatkar’s poem “The Pattern” that runs through The Second Law, but also visually. Could you tell me about the pattern language of your practice?

Sometimes I wonder if I have a sort of obsessive mania about drawing lists of the various ingredients that make the city. By noticing these things and recording them, I can absorb the fundamental structure of repetition and difference. I guess this is also how the subconscious functions: you fixate on certain elements, they penetrate your subconscious and resurface in the form of a dreamscape. That’s what I employed, quite literally, by walking and practicing the city and recording patterns. For me, photography is unavoidably a potential artwork and a potential document, process and product are not distinct. Walter Benjamin spoke about the optical subconscious: something that happens with photography that sometimes we are not aware of. And so I purposely wanted to mobilise images that had taken over my entire life in Bombay. It’s not a survey or a mapping. I’m not talking about topography or geography. There’s this tension between these grand histories of the city and the small, everyday patterns that we observe and that allow us to forge a relationship with it.

I’m reminded of the poem that I sent you by Arvind Mehrotra, “A song of the Rolling Earth,” because it’s essentially a list of repetitions, and a very idiosyncratic one. Repetition can be banal and exhausting, but there’s also tremendous color and specificity within it.

Each city will have, in that way, its own glossary, that’s what makes its own language. Patterns can also be seen as the coordinates of your grid. To quote Aveek Sen, “the grid becomes a potentially totalising system with which reality […] another totalising system, must endlessly play its games of elusiveness and containment, chaos and order, freedom and necessity”. Here’s an image from my studio when preparing for The Second Law. Here the thread turns into a square, a grid.

Part III: Homage

It is 1913. A writer dreams of humble encounters. “I can’t be too disappointed”, he writes, “over not having become a Roman emperor, but I can sorely regret never once having spoken to the seamstress who at the street corner turns right at about nine o’clock every morning”. The man is Fernando Pessoa, the city Lisbon.

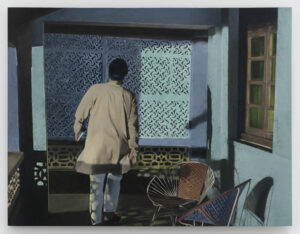

It is 2025. A french photographer leads a reading of an Indian poet’s work. One by one, people read lines. In them, they encounter clocktowers and sweepers, stray dogs and food stalls. On the walls around them: sign painters, vegetable vendors, sea birds, store fronts. The photographer is Philippe Calia, the poet Arun Kolatkar. The City is Mumbai, the city is Bombay.

I see a resonance between your attention to the granular and the work of Kolatkar. What does he do or say about the city that drew you to him?

In a city I first function as a “ragpicker”, a collector of ready mades (like Kolatkar in his poem Three Cups of Chai). Then with these various elements I can experiment with collages. The difference between photography and other found materials like, say, newspaper clippings, is that you add a layer of mediation and “produce” these, and they produce you in turn.

The poem that acted as an epiphany was “Meera”, and the acknowledgement of the coalescence of waste and found objects, of the street as readymade. What touched me, also, is that there is metaphysical depth in Kolatkar’s poetry, but all through a tremendous amount of humour and tenderness for the everyday. One could say it’s also like street photography. It’s not necessarily a wide angle, it’s more of a tight lens that lingers on certain details. It’s the exact opposite of the World Trade Centre point of view that de Certeau talks about. When I speak of epiphany, that’s what I mean: when you feel that your intuition is not a complete delusion, that people who have preceded you felt the same thing about a particular reality. I think of a certain complicity, in the French sense, with other artists who have engaged with the city. I always try to leave some space for homage in the work.

What does it mean, then, as Kolatkar perhaps does, and as you do, to create a portrait of a city?

My immediate thought is that you’re placing yourself, as I said, in a lineage with people who have preceded you. Portraits of cities are like mini-monuments that artists leave behind. Like testimonies addressed to the larger human community.

To properly engage with the city, you need to take a step away from it. You need to see it from different angles and think of another place. You need to displace yourself. It can be walking, or a displacement of objects, or a geographical displacement to another city, but you need that translation moment. If you are in a labyrinth, you’re bound to move to find the exit.