I first saw Tanmoy’s artworks in Mumbai in 2014 at TARQ, Colaba. The works stood in sharp contrast to the world – their muted colours, the fragility of the material, themes almost absent at first glance. But the works nudged you to reconsider, to deliberate, to look deeper into their seeming simplicity. As the years passed, I followed Tanmoy’s works, turning to them for their quiet, their stillness, and their negotiation of unmoving time. Over the years some of these early themes have crossed over into later works, new ones have emerged, while others seemed present even in their absence.

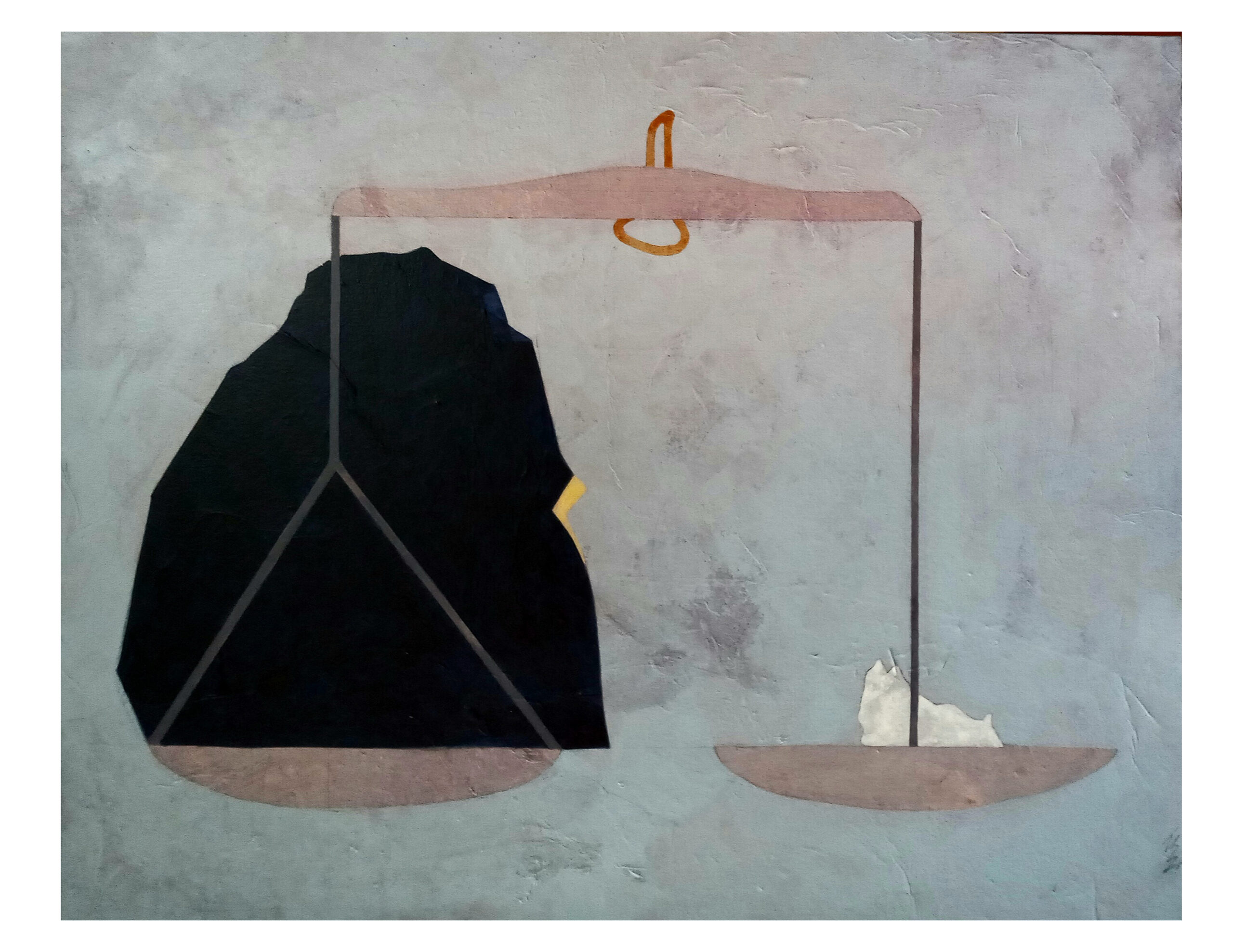

So much of Tanmoy’s work seems to reflect on the notions of home and belonging, an engagement with the domestic and the mundane. Tanmoy returns consistently to a kind of ‘home’ – the simple outline of the roof as it bends to meet the shuttered window, or other structures that seem more makeshift. The weight of “home” bears down heavily on us as we come to reconsider what it means to belong, especially as we are caught in the heartless destruction that punctures the time we live in. Silhouettes are made to emerge subtly through the layered technique of his hand. We piece together the past layer by layer and an opaque stillness gives way to forms that throw clues at us, like fossils. In “Weigh up” a more recent work shown at the Gallery Espace (New Delhi) Tanmoy returns to the theme of object.

A scale balances a large boulder-like form, jagged, angular, like a beast folded up, seemingly unforgiving as it sits against a fragment of itself. The scale does not move. It does not bend. It does not measure. It stays in Tanmoy’s characteristic stillness. I have often thought about this work, the distance it draws from us – who want to reach in and tip the scales, to make right, to measure, to judge and demand.

Perhaps Tanmoy, as artist, does not yield. Perhaps, instead, he references back to old texts and Zen stories, where monks in moonlight trace over sand gardens considering the moment as it arrives, only to be replaced by another. Perhaps Tanmoy just wants to leave the work there for us to encounter. What the works seem to offer is, in many ways a primordial origin myth, stories at the very beginning of time, before they are heard and retold, made anew with every teller.

The almost monk-like fascination with the object – a refusal to make ‘right’ invokes Tanmoy’s years at Shantiniketan in the 90s. Tanmoy remembers the years as being in flux, for the institute that had begun to look towards other centers of artistic expression and learning. But for him, everything was already there, the barren landscapes of the Santhal villages that surrounded the institute became his solitude where he could introspect. In an interview Tanmoy observes, “The rich legacy of Kala Bhavan was vividly present but in different scenarios, there was a vacuum as one was faced with a challenge to reinvent and move. I chose to dwell in the vacuum, I did not want to lose the essence of what made this institution unique yet significant and bring back my life and time at Kala Bhavan into my work.”

It is this tension that best represents Tanmoy’s ‘struggle’ as an artist. His works often suggest a tense dialogue between the natural world and domestic tools, the environment in collision with the effects of mechanisation and industry. The tense, even predatory effect of industry doesn’t become apparent when you first engage with his works. But Tanmoy works layer upon layer of both paint and paper, creating an opacity for the works and even as he makes objects into gestures, the tensions begin to reveal themselves. As we come to encounter his works, the artist encourages us to contemplate the complexity of being, to dissolve, disperse and become deeply intertwined. It is also the textural quality of these works that lend themselves to a sense of the fragile – where rice paper is pasted to board before colours are added through a process of layering. These layers, that are added and taken away, objects rendered in a colour palette that meanders between the palest pink and shadows of green, heighten the sense of things forgotten and things remembered. It seems almost like a universe that cannot be disturbed but instead chooses to throw us headfirst into the encounter.

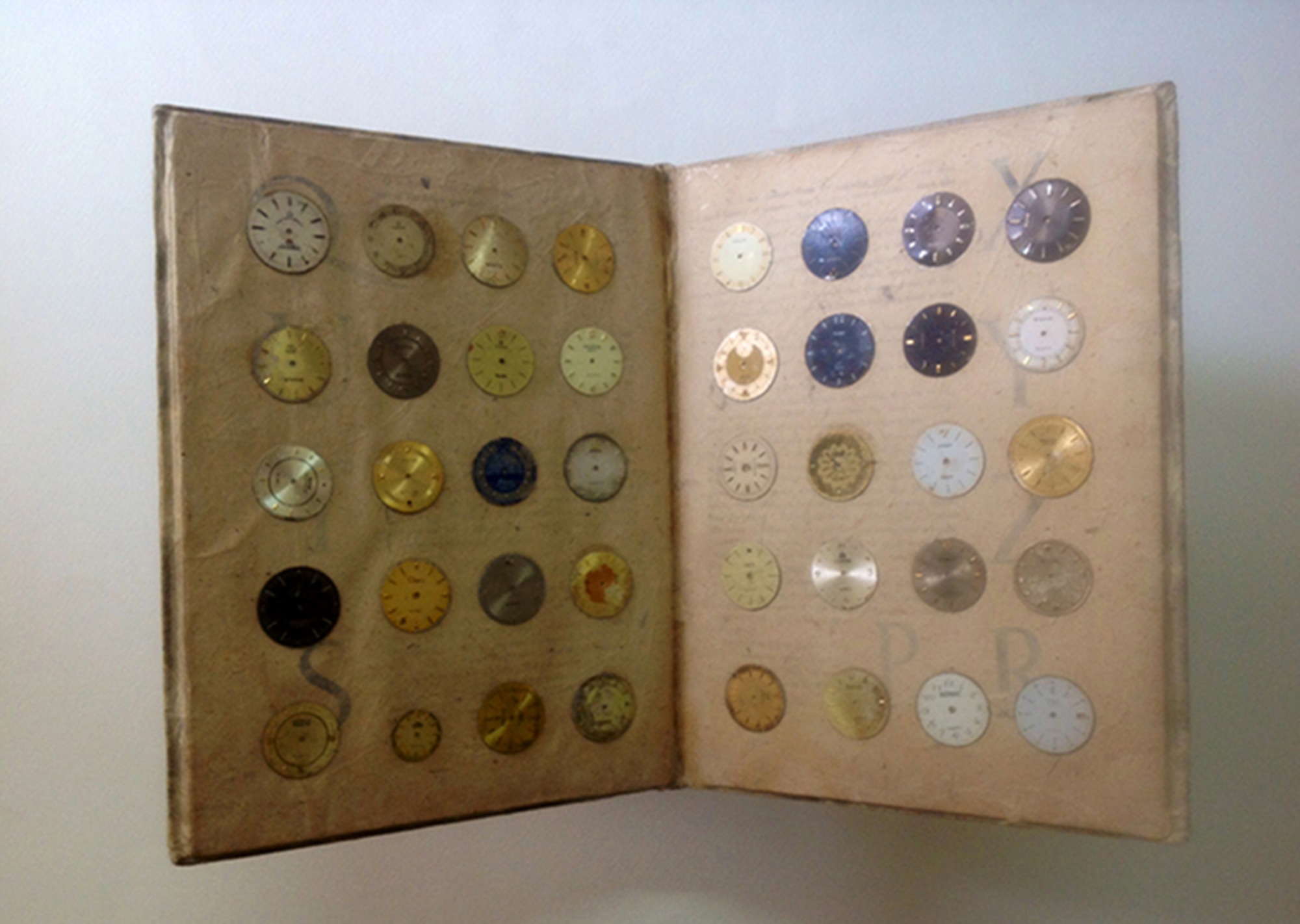

A work entitled ‘The Time Keeper’s Manual’ (2014) bears the same loss of time, and the recall of memory where forgotten objects metamorphosise into a landscape of the remembered.

In this work the artist crafts a found book, moulding it with rice paper, until the book itself, the repository of knowledge, no longer comes to bear upon its original meaning but instead takes on a different subjectivity. The unusable watch dials in gold, black, white, and grey fill the pages. They no longer embody Time. Instead, they create their own sense of rhythm and space – move along the page as if they were an exploding constellation searching for new meaning, fresh purpose. They begin by dripping on to the page, settling into a formation, reaching out like Orion’s belt, and finally coming to bear as sight. Watch dials without arms negotiate an abstract temporality, grasping for new meaning even as their function is lost.

In a study that came to be known as the ‘Phantom Limb’, neuroscientist V S Ramachandran found that by placing a mirror where the limb had been amputated patients claimed to ‘feel’ sensations in the missing limb. If we were to extend this theory to include and encompass larger themes, and in this case we notice that the form and the body, both emerging from the same moments of memory begin to morph, melding to create an image that does, in many ways, complete itself. As the mind begins to re-member the absent, it pieces together fragments, sometimes as far back as an ancient memory beyond time and loss.

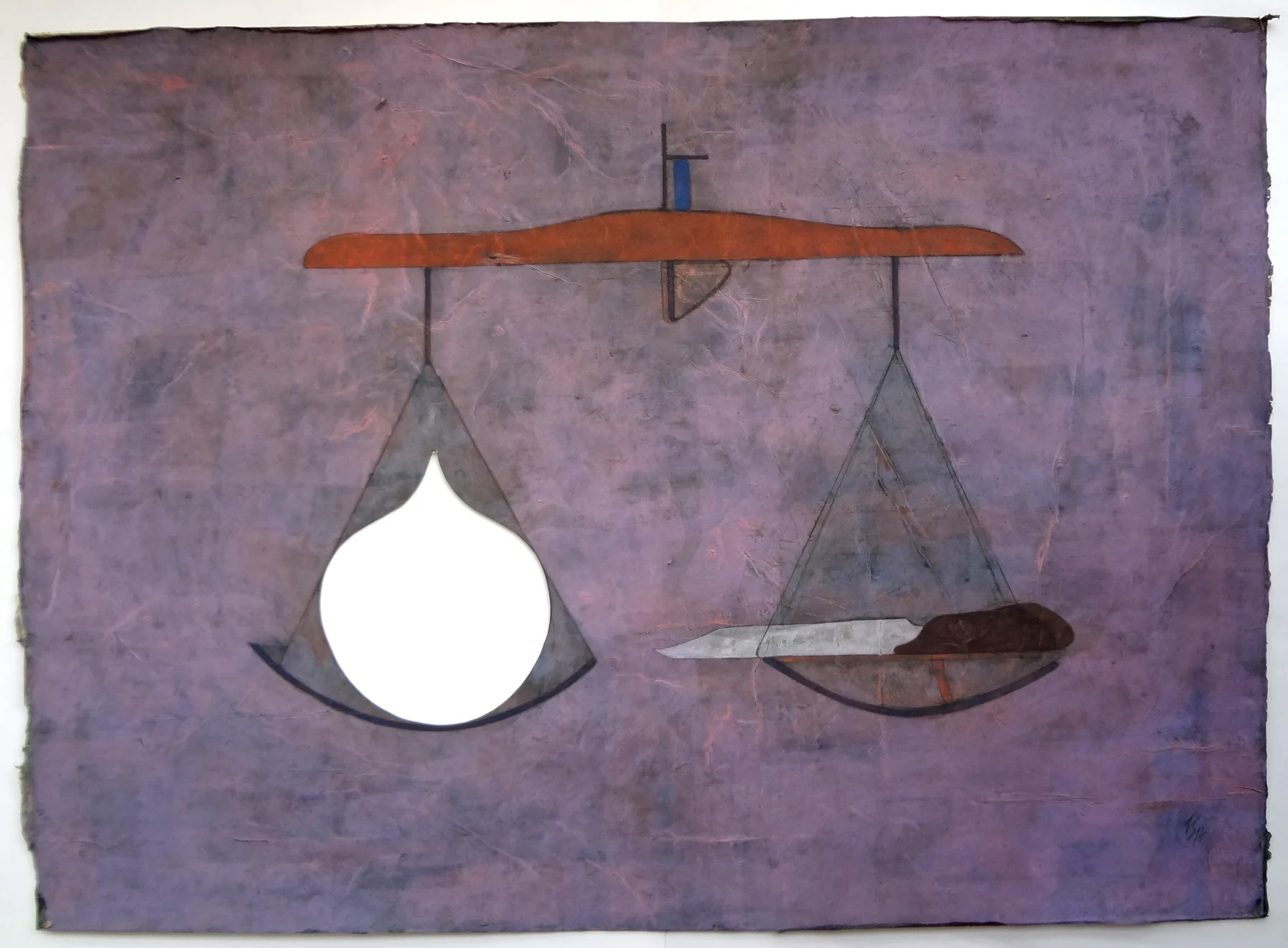

A work from his earlier show, ‘The Persimmon and The Knife’ emerges, in many ways, like the Phantom Limb, where we access memory through the missing fruit.

The viewer is confronted by the loss of the object, which is cut out of the work but draws on the memory of its existence; the negative spaces that the fruit comes to occupy in our mind. While language draws us back to the meaning of both the subject and the object, the play of the loss of the object creates new meaning. The question that Samanta poses then is whether the meaning of the object is created by language or does it take on new meaning by its ‘absence’.

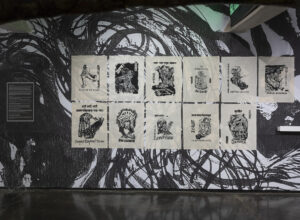

Among Tanmoy’s latest works, there is a work that I have looked at again and again while writing this piece. In the untitled work (24” x 32”) shapes collide, giving way to pragmatic forms carrying with them the stories of our times.

I begin to understand Tanmoy a little more as he leans ever so slightly into the role of cartographer. Buried to the left are the famous watch dials – a recurring theme in Tanmoy’s work. The artist contemplates time but time without movement, perhaps even without Time itself. Serrated edges, like borders, cut through the work – those connected are now lost and separated. The work seems to pulsate with an ongoing conversation of power and politics, of lands ravaged and borders changed.

Tanmoy sits still in this conversation; his words hang midair as we try to catch a missing phrase to make sense of the loss. The very center of the work reads like an ancient map, the sort of map that we have encountered in the works of Piri Reis (1470-1553). A city of streets and domes, alleyways, and riversides, seen from every angle. Perhaps a city that sits at the very edge of time, trying to make its way into the larger canvas, the fragile city. Is Tanmoy offering us a glimpse into the edge of time, at the threshold of change, against the abyss of destruction? As our eyes move across the canvas, we are drawn to the only deep red that sits along the right, a shape so familiar in our times. Perhaps it is the present, looming large. A fragile world teetering at the edge. But Tanmoy is no prophet, he does not choose to instruct, he is instead the Shakespearean ‘Fool’, the storyteller with a palette, he only wants to leave you with a story, make of it what you will, because you will.