Artist Anupam Roy’s solo exhibition is a culmination of his many years of intense engagement with multiple systemic distortions. A survey of his career-path suggests an evolving body of work that variously explores ruptures and fault-lines in the relationships between the body, land, ecology, nation/state, and self: For his final thesis at Ambedkar University New Delhi in 2016, he studied the spectacle of collectivity through a show titled Excess which launched in Ambedkar University New Delhi. In 2018, his exhibition A Beautiful Contract at Banipur, West Bengal, explored the fraught politics between a land and its fragile inhabitants along with filmmakers, performance artists, and other creatives who were invited during his residency program at BASIC. At Project 88 (the site of the show “Ing…”), in 2019 his show titled De-notified Lands explored the relationships between more-than-human lifeforms and their migratory identities on land, and a 2024 exhibition Time is Sloshing followed the nonlinear, zigzagging nature of time. These diverse, and eclectic creative tributaries surge seamlessly toward this flowing river of an exhibition, nestled in the heart of Colaba’s pasta lanes and fire brigade.

View from the Gallery – Project 88. Exhibition: “…ing: Sceneries Without Sovereignty” by Anupam Roy. Picture courtesy: Mr Rane

In Anupam’s own words, the nomenclature of the exhibition – “…ing: Sceneries Without Sovereignty” (Oct./Nov. 2025) – embodies his journey of “trying to understand the present continuous tense”. Various collaborative artworks explore different forms like zines, posters, paintings, poems, film, and sculpture. Even the title of every piece is a continuation of the present: “…ing_1”, “…ing_2”, and so on, and each work seems to be pulsating with a heartbeat, telling us ‘we are here, we are alive, in the present, in the now’.

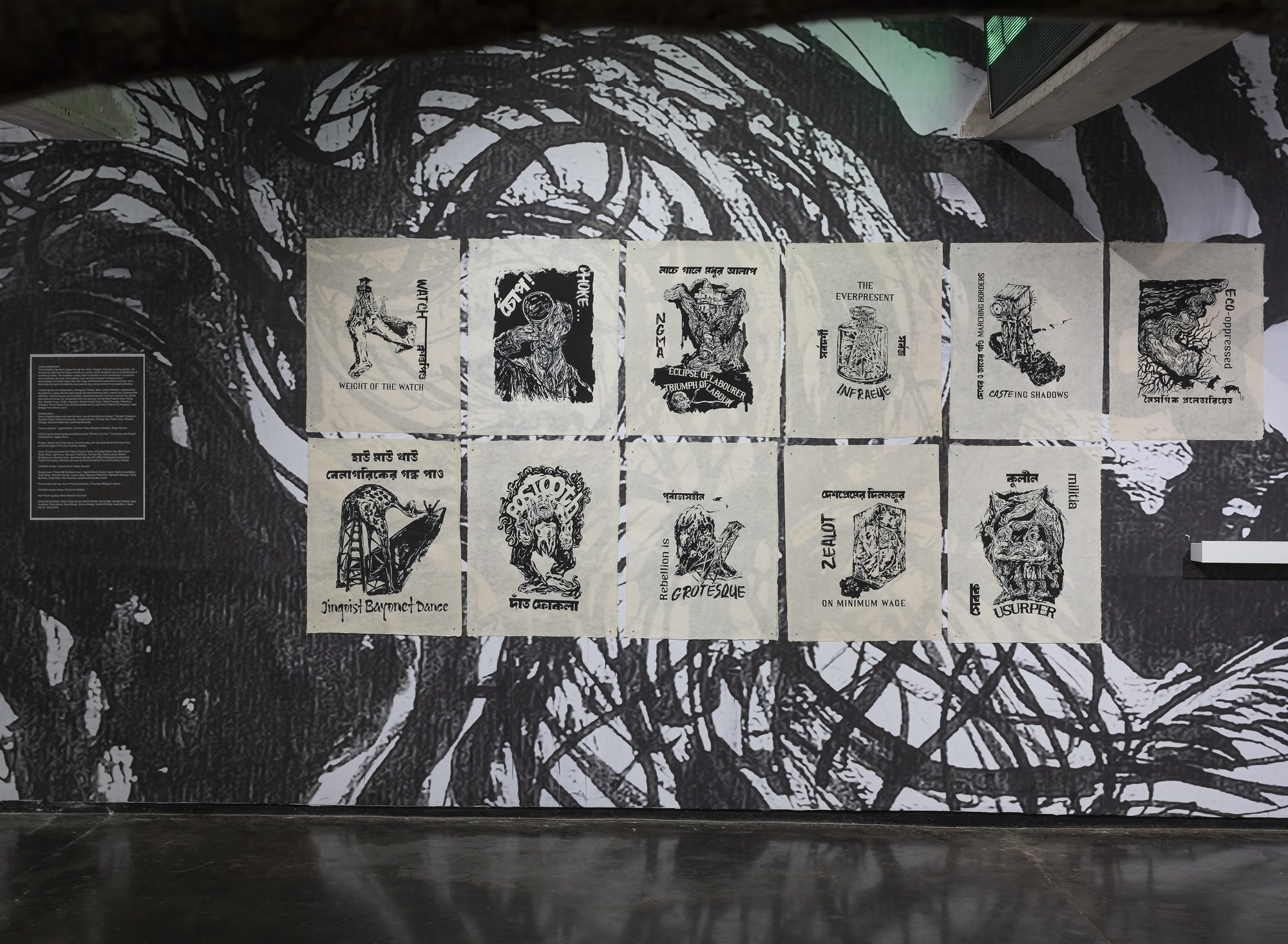

Posters reminiscent of Soviet-era public artworks, Banksy’s London graffiti, and CPIML prints found in the streets of Kolkata welcome visitors at the entrance. Strong statements such as “Rebellion is Grotesque” and “Casteing Shadows” are juxtaposed with jarring illustrations of monstrous creatures holding, or being held by, ordinary objects and everyday contexts: glass bottles, slum housing, pole towers, and places of worship. The artist sheds light on one of the most pressing issues facing India, and especially Bengal, today: SIR and immigrant-based violence. These posters highlight how working-class people, Bengali Muslims, and those from disenfranchised castes have been serially targeted by the CRPF, Border Security Forces, SIR surveys, and new laws such as the CAA-NRC. One of the posters highlights how the border hinges upon the creation of identity based on caste, religion, and otherness, while another emphasises how immigrants are either given undignified jobs with minimum wages within the country, or treated as less than human by the BSF and CRPF when eradicated. Victims of these border violences haunt Anupam, and are remembered through these illustrated posters.

In another work, a poem by Moumita Alam called “Where is my City?” tickers in green font on an LED screen above our heads—an almost threshold-like archway opening up into the next portal of artworks: zines and a short film, made in collaboration with Yogesh Barve. One of the zines flips through a poem by Vidrohi (Ramashankar Yadav), Nayi Kheti, while another compares how capital mines natural resources and intellectuals mine subaltern experiences. The work directs its commentary squarely at the urban elite audiences of a South Mumbai art-gallery, who speak self-righteously and charitably about subaltern lives during their dinnertime conversations…

I search for the city of mine

Where is it?

where it was!

my memory gets blurred.

It was in the ghettos of Godhra

or maybe in the valley of Narmada.

No No

It was in Muzaffarnagar

it was in Nellie

No, it was on the bank of Jhelum

or in the deep forest of Bastar

it was in Kucheipedar

it was on lush green pregnant lands of Nandigram

It was in Marichjhapi.

It was in Jafrabad,chand bagh

and have forgotten.

My memory betrays me always.

My memory has become annals

mixing up dates, years, places

2020,1947,1964,1968,1984,1983, 1989,1992,2002,2007,1979

and still recording…

All the cities of mine are smelling warm gun-powders

the siren of the khakis and that killing shout

all are the same.

Where is my city now?

you have devoured and are devouring it through your hatred.

– © Where is My City by Moumita Alam

In the corner lies a small television box with a short film titled “7 broken stories”, playing on loop. After walking through assaults of poetry, zines and posters, visitors are made to suddenly slow down, sit in front of a screen, and spend thirty minutes in stillness. There is something powerful in this deliberate formal excess of the different works – viewers are overcome with a sensory overload, urged to look at eclectic dimensions of visual, auditory, and textural surfaces. The formal complexity appears to echo the thematic force of rebellion, and revolution, that surface in diminutive capsules or displayed boldly over one’s head, through language and imagery that is illuminated and captivating.

In another work, a series of gargantuan paintings—96×60 and 96×72 canvases—each one interspersed with microscopic photographic tiles—4×4 in size—frames rural landscapes, featuring labouring humans, animals, soils, machines, environments, fires, and homes. The large paintings are explorations of the grotesque body, anthropomorphic in nature, and throbbing with life in an everchanging environment. These canvases are “painted” with acrylic/oil colours, but also with sand, cement, and a mixture of earthen elements. Most of the humans that he painted have their faces covered, or missing, emplaced by animals, tools, and ‘objects’ of labour. The distorted bodies in their environments serve as a commentary on how a person is reduced to their labour, and how labour is tied to questions of identity, migrant movement, and sovereignty.

Even the biodiversity that surrounds each of these characters in the acrylic paintings has been carefully selected by Anupam. None of them are essentially “sacred” or “holy” animals; they are, in his words, “ashubh”: blackish cats and foxes, the “asura”-esque buffalo, the night owl. As for the vegetation, none of it is native to this soil. For instance, the gulmohar brought here from Madagascar, and slowly adapted to local climates and soils. A clever reminder that anti-immigrant rhetoric, which is often deeply entrenched in the idea of one’s “roots”, stands flawed, even in the most “rooted” organisms. Artists and poets who have inspired his ideas lurk around the corner, hide behind canvases, peek out of different forms and materials. The spectral presence of sculptor Ramkinkar Baij stares back at us in the painting, “…ing_5”, while “…ing_6” pays tribute to K P Krishnakumar’s 1985 fiberglass sculpture, “Thief”.

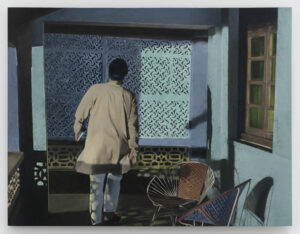

Anupam includes a series of framed gouache works inspired by the Delhi riots of 2019-2020 in this exhibition. Each one portrays apocalyptic domestic scenes—dilapidated homes and burnt belongings, the resulting ravages of hate mobs. He first picked up archival photos of the riots, took xerox copies of them, and then painted over the copies. This layered approach allegorises the many layers of time and space that separates gallery audiences inside sanitised, gentrified spaces, from the real events of conflict and violence that rocked the national capital.

In the midst of all of these artworks that speak to systemic oppression, there is a silent moment stolen through an oil-on-canvas painting of a solitary bed in an empty room, with one googly eye stuck on the portrait in an almost absurdly comical fashion. “This image is inspired by two historical contexts: the recent lockdown in India and Somanath Hore’s ‘Wound Series’ of artwork. “Similar to the ‘white on white’ concept in Hore’s work, my image features a completely white hospital bed and an eye either resting or embedded in a pillow. It aims to convey the story of witnessing pain inflicted by state apparatus, highlighting the bodily humiliation experienced under our current authoritarian governance,” says Anupam. The lynched body is painted in oil, a medium that resists erasure and remains almost immortal through time – paying tribute to the human lives that have been far too easily obliterated. A profound moment of intimacy that seems to numb down the noise of riots and destruction, this portrait hangs between paintings of communal violence and mob lynchings.

If every poem has a volta, a turn, then this exhibition’s volta lies at its centre – a movable wall slicing the gallery diagonally – that has been covered with a diptych drawing titled “…ing_10” and “…ing_11”. The work is a rolled-out paper of 5×35 feet, both sides featuring Anupam’s drawings of wetland species and flora fauna, representing two sides of the same biodiversity coin. One side has dead species, while the other portrays them alive, snarling and roaring freely in the wetland. The artist has painted this large work entirely in black chemical compound—industrial material – the detritus problematises the very construction of the space in which this work is exhibited: “the medium itself of art is violent – landscape paintings and botanical drawings were used for colonial endeavours. We cannot forget all that. So when you paint and draw, you address that. Also it’s important to show that these things exist within the gallery also – casteism, islamophobia, violences.” The couplet footnoting the drawing takes from Binoy Majumdar’s poem:

A Resplendent Fish

Binoy Majumdar, translated by Supurna Dasgupta from Bengali (published in DoubleSpeak Magazine)

A resplendent fish once flew up

in the air only to dive back again in the blue clear water

And this pleasurable sight

Ripened the fruit with an aching bloody blush.

Threatened cranes fly, ceaselessly they flee

Since everyone knows that beneath their soft white down

There’s warm, warm flesh and fat.

Short rest stops by fatigued hillsides

All water-songs evaporate, and yet

At this time, you oh sea-creature, you… you…

Oh look at the scattered diseased trees

The expansive vegetation of all this world

Long, long sighs of exhaustion rage through it all;

Yet the trees and flowering plants stay apart in their plots

Dreaming of breathless unions.

– © A Resplendent Fish by Binoy Majumdar

In a way, this elliptical, evocative poetry summarises the present continuous tense that anchors Anupam’s exhibition. The works, through their formal abundance, resist fixation, asserting multiple presences that resists and reformulate the politics of sovereignty.

A bamboo sculpture, possessing an almost-eight hour-long sound piece (worked on with with artists Thomash Changmai, Subhash Deka, Hemant Sreekumar, Swastika Kundu, Tanmay Das, Labani Jangi), connects both sides of the drawing, the dead and the alive, the front and the back, the living and the grotesque. It hovers and extends over both sides of the paperwork, stretching across the room and hanging over our heads. Its magnanimity lies in the ‘spits’ and ‘spurts’ of sound emanating from the bamboo hole. “I realised even if you want to control it, you can’t. I thought that the sound would travel from one side to another, but now [the sound is] leaking,” Anupam says to me. A leaking sound. How poetic, how unintentionally glorious in its errors.

To exist without sovereignty is to exist without an internal source of validation; and the artist resists this through his art that is constantly trying to reach self-determination. He finds the majoritarian perspective of “going back to our origins” a futile task; looking for a singular source of historical identity is impossible, since our identities are constantly being formed. They are constantly “[form]…ing”; he explains to me: “for the nation, I am Anupam Roy. The intercaste marriage of my parents, my caste, gender, nationality, religion – all of this is written. But I didn’t choose any of these identities; they were imposed upon me. If you look closely, I grew up in a border area – slowly, my identity starts getting complex. See how it is constantly shifting? Similarly, every few kilometres the soil changes, and every fifteen kilometres the local language changes, just as the birds, plants, and water also do. There’s a traversal quality to existence.”

Anupam’s philosophy does not end at the confines of the gallery. The work is geared to manifest into magazines, articles, and a possible two-volume book. His art exists in the present continuous, in the “…ing” of self-determination, and creative vulnerability. The bamboo sculpture acts as the dial of this absurd clock in which time is sloshing against the collapsing edifices of his art – a potent reminder of our own mortality and ephemerality. Sound still leaks from the bamboo, and they say it needs fixing. But what I see here is a neverending, tragicomic present continuous tense. Constantly flowing through space, moving in form, changing shape, violating landscapes, resisting politicisation, claiming self-identity… being. In a state of maniacal continuity. Sceneries without sovereignty follow no logical trajectory. They exist in a state of surreal abandon.