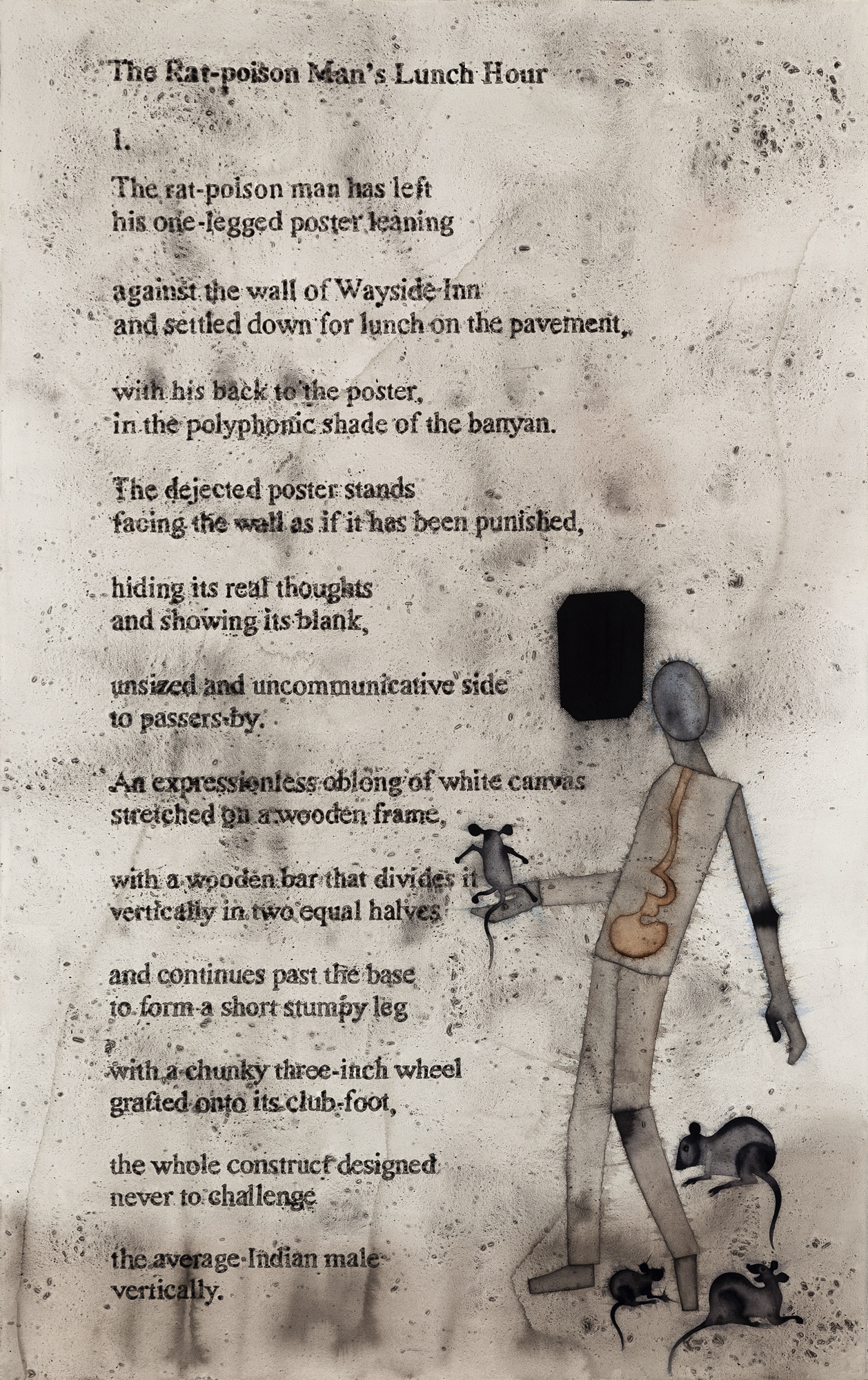

Artist Atul Dodiya’s reimagination of poet Arun Kolatkar’s poems from Kala Ghoda poems (2014) poses the viewer with a dilemma – are the artworks to be seen or read? From The Rat-poison Man’s Lunch Hour to Pi Dog and Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda, long extracts of poems are reproduced with illustrative figures painted in watercolour.

From his wanderings, and a table at the Wayside Inn cafe at Kala Ghoda, Kolatkar observed and documented the street life of the city in this collection, which is populated with marginal figures (the rat-poison man, pinwheel boy, hipster queen of the crossroads), stray dogs, cast-off objects and garbage. Dodiya’s terse, emaciated outlines, some of which have a skeletal head or have their bones and innards exposed, are connected to the poems in direct as well as oblique ways. The black charcoal blobs and the ashy hue of the paintings refer to the tormented psyche of the city migrants. “The migrants who come to the city to earn a living end up feeling trapped and marooned in the city as if they are in a Kala Pani prison,” says Dodiya.

“I have a painting called Sunday Morning Marine Drive (1995), in which you can see the Arabian sea over a parapet. The sea is completely black, it’s literally Kala Pani. That is where the black spots come from. They also break the literalness of the works.” The Kala Ghoda series that portrays a particular milieu of Bombay, frames poetry and art as an extension of place, transforming the city into a poetic text to be perused. The act of reading is the work.

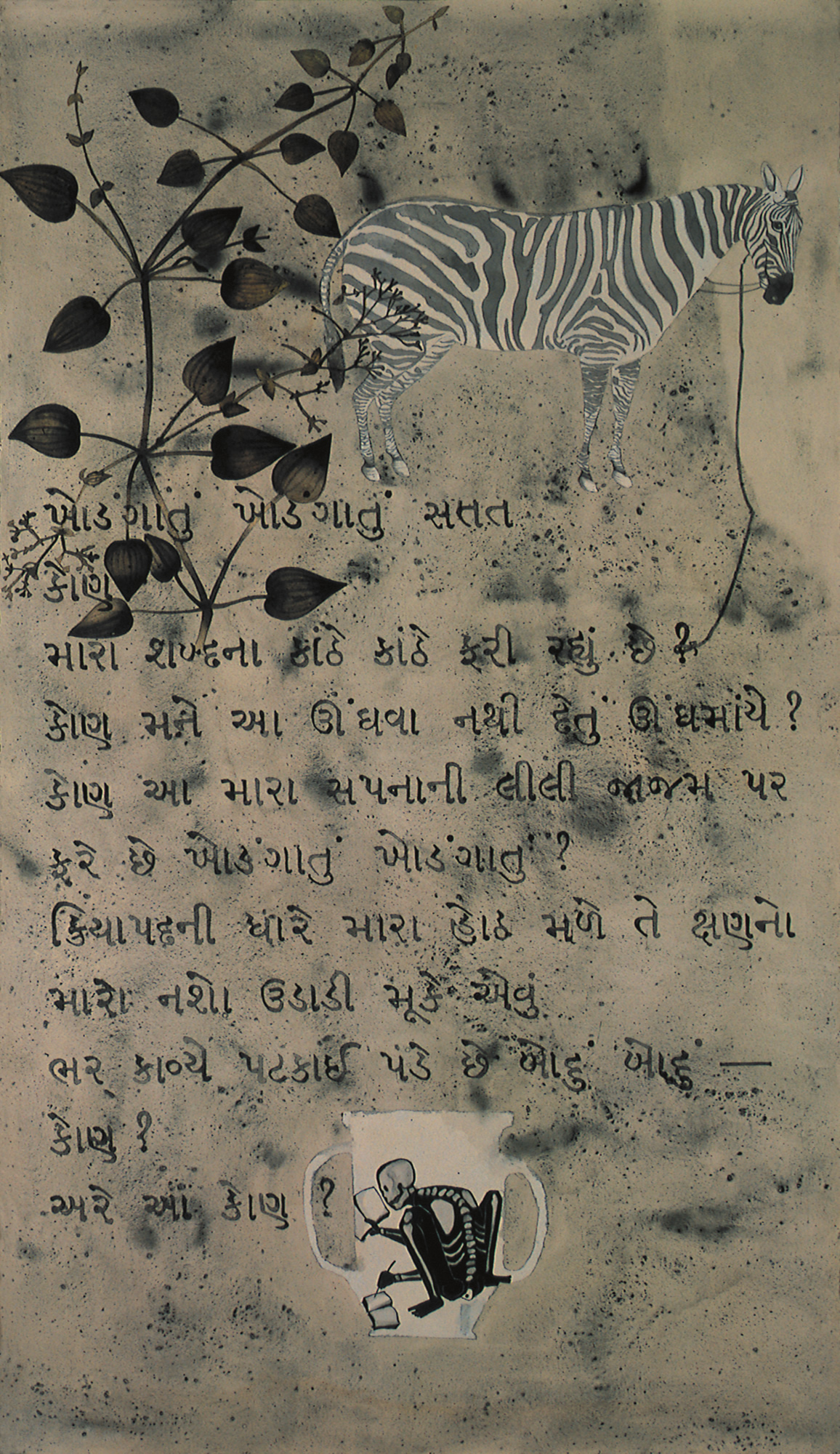

This tension between seeing and reading through a convergence of poetry/ literature and art is present in the artistic practices of Zarina, C Douglas, Baaraan Ijlal, among others. Poetry lends rhythmic text, adds elements of sound and shape, besides providing resistance to institutionalised language. The use of poetry must be further contextualized within the larger framework of incorporation of various forms of writings into art. Dodiya, for example, is enmeshed in the world of diverse visual and literary cultures and his art works are a melange of allusions and references. He has cited poems by Gujarati poets Ravji Patel and Sitanshu Yashaschandra in Antler Anthology (2004), and his show Bako Exists. Imagine (2011) renders a fictitious conversation between Gandhi and Bako, a young protagonist featured in the Gujarati poet Labhshanker Thaker’s writing. Apart from Chinese calligraphy, miniature traditions, Dodiya was influenced by Rabindranath Tagore’s early paintings that started as scribbling or a kind of erasure. “While writing a poem, if he was not happy with certain words, he would cancel words with a pen and ink,” says Dodiya. “Those words removed by scratching became a floating, abstract form. On one side, you have precise, readable words, and next to it, on the same page there are dancing forms – the meaningful and meaningless are juxtaposed together.”

Dodiya also looked closely at VS Gaitonde’s works, some of which had letters drawn on a paper. “They look like some kind of text, but you can’t read them, they’re essentially notional forms,” says Dodiya. “Whereas, I thought, what if I write something, but it’s absolutely readable, like you know in a language like Gujarati or Hindi or Marathi or English, so that seeing and reading happen simultaneously, both of which are essentially the process of seeing, as reading cannot happen without seeing.”

Like Dodiya’s inspiration by the literary milieu helped shape his works, C Douglas was steeped in the modernist and symbolist poetry of T.S. Eliot, Rainer Maria Rilke and Rimbaud. His work has to be located within the Madras art movement of the sixties, that integrated writing and visual art. Helmed by KCS Paniker’s Words and Symbols series (1963) that used script decoratively, textual references started appearing in works of Reddappa Naidu, KM Adimoolam, SG Vasudev and Douglas. “This whole idea of how they started using words goes back to the intent to make the line the primary expressive tool because they thought the line, which is the basis of drawing and writing, has a very important role in Indian art,” says art historian and curator Vaishnavi Ramanathan. “That is where the usage of script started. Initially they used it as a motif and then it became an independent element by itself.” For Paniker, script is not a meaning-making signifier, but a visual element.

On the other hand, Douglas’s inclusion of poetry and writing in his art works to create transitional emotional registers of the human body. Tamil writer MD Muthukumaraswamy in his article C.D Douglas: The Mind of the Artist writes, “By cohering the word, line and the human body, Douglas invents a new relationship between the things that exist only in the sphere of art .” The series Blind Poet and Butterflies (2011) by Douglas explores the idea of a blind poet modelled on Milton whose vision is represented by butterflies with eye-like shapes on its wings, along with a scattering of poetic fragments layering the pictorial space. “Douglas is always exploring the in-between state in his works,” says Ramanathan. “There are foetal forms, blind poets and figures in the grip of existential angst. The paintings are steeped in a twilight zone, marked by erasure and absence. The use of words and images reflect this state of in-betweenness, sense of incompleteness and non-linearity.”

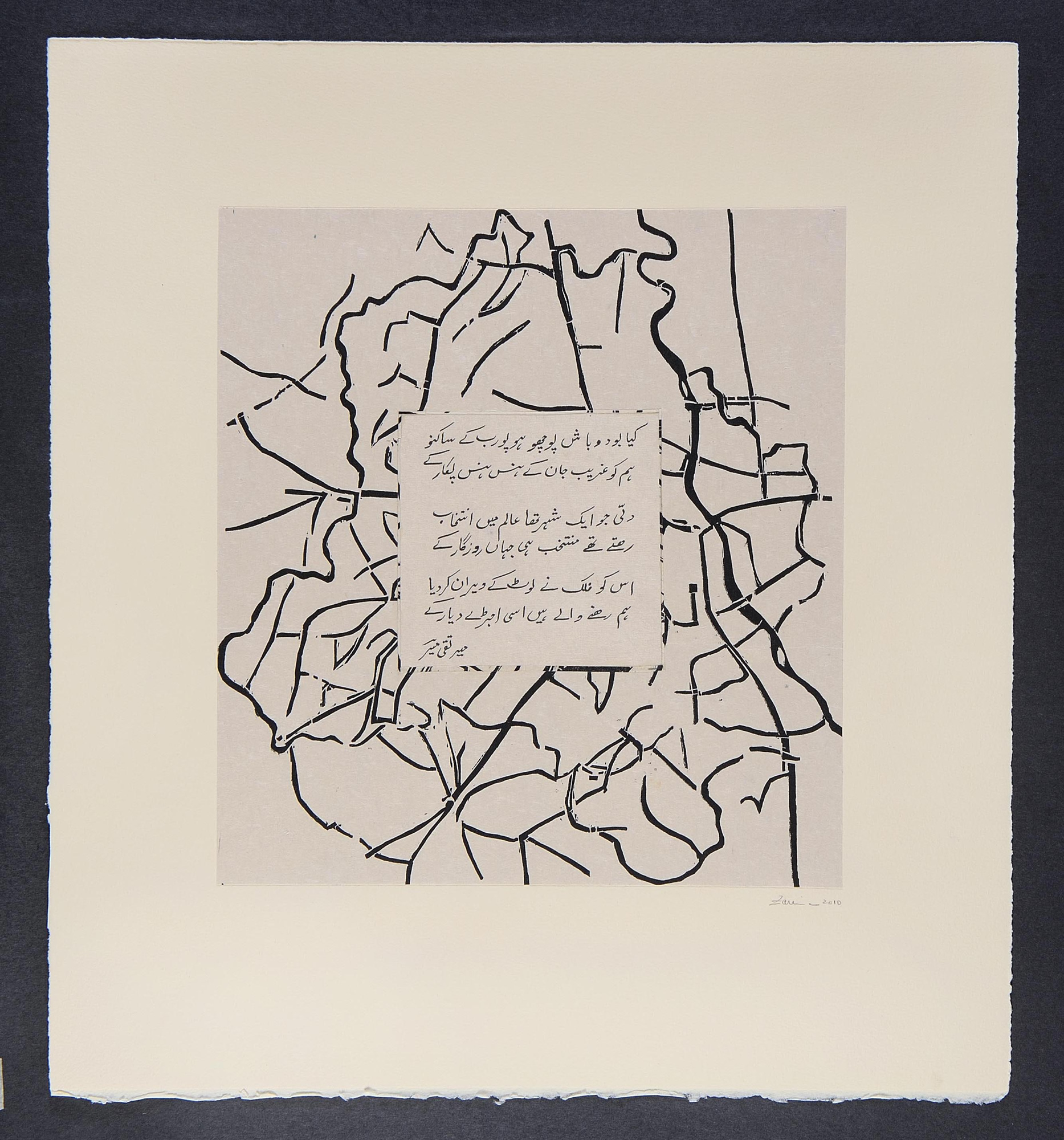

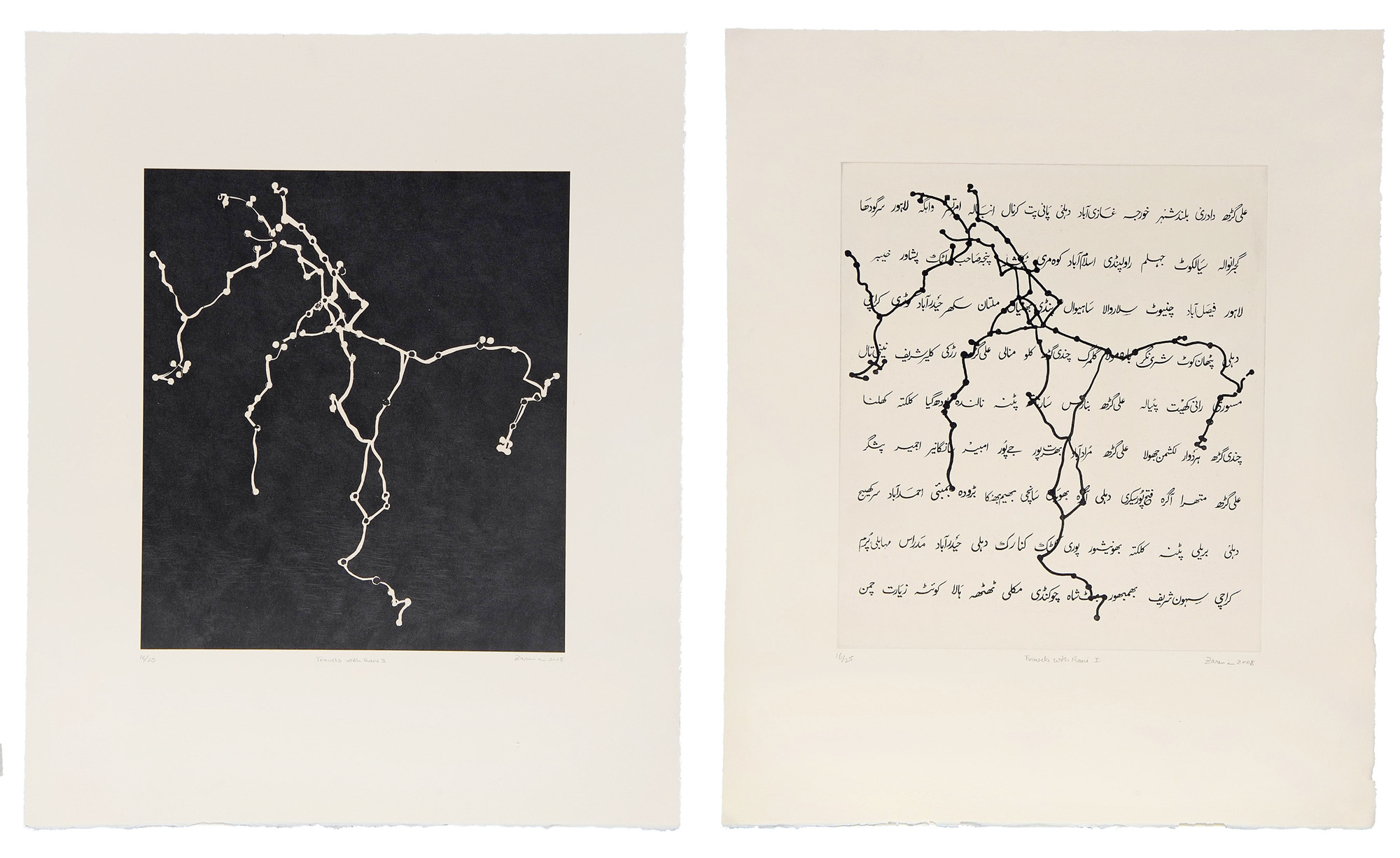

The in-betweenness of uncertain belonging, and acute nostalgia wrought by displacement are underlined by Zarina through Urdu verses and script in her works. Zarina’s peripatetic life unleashed a pining for lost homes. Brought up in Aligarh, she moved to Lahore after Partition, then travelled across the world with her diplomat husband, before settling in New York. She cured her homesickness through aesthetic recreations of bygone addresses. By deploying geometrical abstraction that often evokes Indo Persian architecture, as reflected in silhouettes of stepwells, arches, niches and courtyards, she constructed an architecture of dispossession. The power of the Indo-Persian tradition on her imagination is underscored by the use of Urdu text in works like Untitled (Map of Delhi with poem by Mir) (2010), where couplets by Mir Taqi Mir are superimposed on a veiny, abstract aerial map of the city.

One of the couplets is Mir’s famous response to the upstarts of Lucknow who chided him to name his fallen hometown: “Delhi that was once a select city in the world, where only a chosen lived of every trade/The heavens looted it and left it desolate , I am the citizen of that ruined place.” To non readers of Urdu, the serpentine lines of the city map echo and merge with the undulating Nastaliq to form filigrees of memory and desire.

The choice of Urdu is deliberate for artist Baaraan Ijlal, for whom Urdu is not a decorative motif. Ijlal’s father is the Urdu poet Ijlal Majeed and her childhood was spent immersed in Urdu newspapers, literary magazines, her parents’collection of Urdu poetry and novels. She often uses Urdu couplets in her narrative-figurative works. “The use of Urdu in my work is instinctive but also intentional, a way of resisting the slow fading of Urdu script from public life since Partition,” Ijlal says. “When viewers cannot read the script, the experience of exclusion is not just formal, it is historical, it mirrors the condition of the language.”

Her works often fuse myths and socio-political realities. The lines of poetry are companions that hold secrets of the painted narratives. In Hostile Witness: Between Dusk and Dawn – Women, Land and Borders (2024), you see a teeming house being besieged by winged creatures with pistols as heads. The wall of the Pre-partition style house with arched windows has an inscription by Rajinder Manchanda Bani, “Kaise log the, chahte kya the, kyun wo yahaan se chale gae /Gung gharon se mat kuch pucho, sheher ka naqsha dekho tum (What were those people like, what did they desire, why did they leave this place / Don’t ask questions of mute houses, look towards the map of the city).” The house is the ‘hostile witness’ that silently holds memories of historical events of displacement and rupture, much like the Urdu language. Even when the Urdu lines are unread, their very presence becomes a way of remembering the flawed maps of places and languages. “Even if Urdu could not be comprehended by someone, it can be encountered,” says Ijlal. “It asks the viewer to stand with what cannot be fully possessed, just as we must learn to stand with grief, memory, with the stories of those who have been displaced and silenced.”

While poetry is the apotheosis of language, the script is its basic unit. In 2004, Gulammohammed Sheikh had started Alphabet Stories in response to the authoritarian move to change children’s text books that replaced the liberal and open-ended syllabus of children’s books by a majoritarian, mono culture. “It brought about a drastic change in historical authenticities foisted with false narratives misleading and muddling young minds,” says Sheikh. “In this work made in the kaavad form, I used images of alphabets used in text books pasted in the form of collage, painted the alphabets and juxtaposed them with words both conventional and freshly coined by me” In the two water colours bearing identical titles (Alphabet Stories 1(2000) and II (2004), alphabets were painted with different words not used in text books, to indicate multiple meanings contained within each alphabet. The other one had images for alphabets slashed in black paint to indicate assault on the idea of alphabets.

All these artists animate their works with words that must be perceived in singular ways. Dodiya’s works foreground complete, meaningful sentences and it is an extension of his figurative language. Douglas’ use of non-linear fragments evoke a state of suspension and liminality, while Ijlal insists on an encounter with fractured history. On the other hand, Gulammohammed Sheikh harks back to the tradition of ragamala paintings for a sensorial experience. “In the traditional ragamala folios, text and image are usually combined with reference to a musical melody to be imagined by the viewer,” he says.

Poetry has been deployed not only for its textuality, and visuality, but also for its orality by artists like Shilpa Gupta and Amol Patil in their multimedia installations. Gupta believes that words can manifest, that poems are poultice or healing talismans. By whispering verses of banned poems into medicine bottles, Gupta in Untitled (Spoken Poem in a bottle) (2018 onwards)’released’ potent, poetic charge in confined spaces. Her work For, in your tongue, I cannot fit (2017-18), with a huddle of hundred microphones suspended over hundred metal rods, their tip perforating the bowels of a white sheet overwritten with a poem by a poet who has been incarcerated, transformed the surrounding exhibition space into a cathedral of sibilant, defiant voices.

The resistant power of poetry is channelized by Patil , who repurposes ballads from family archives with lyrical interventions by a contemporary powada performance group Yalgaar Sanskrutik Manch in Black Masks on Roller Skates (2022) to build a strong narrative about Dalit rights. Patil’s grandfather was a powada shahir, a poet and troubadour who would travel across villages narrating epic tales and ballads lending voice to anti-colonial struggles and socio-political concerns of the Dalit community. The performative work Black Masks on Roller Skates (2022) features a video of sanitation workers moving across city roads on roller skates, sweeping floors carrying a radio which plays powada songs by Vilas Ghogre, a prominent Dalit activist and poet.

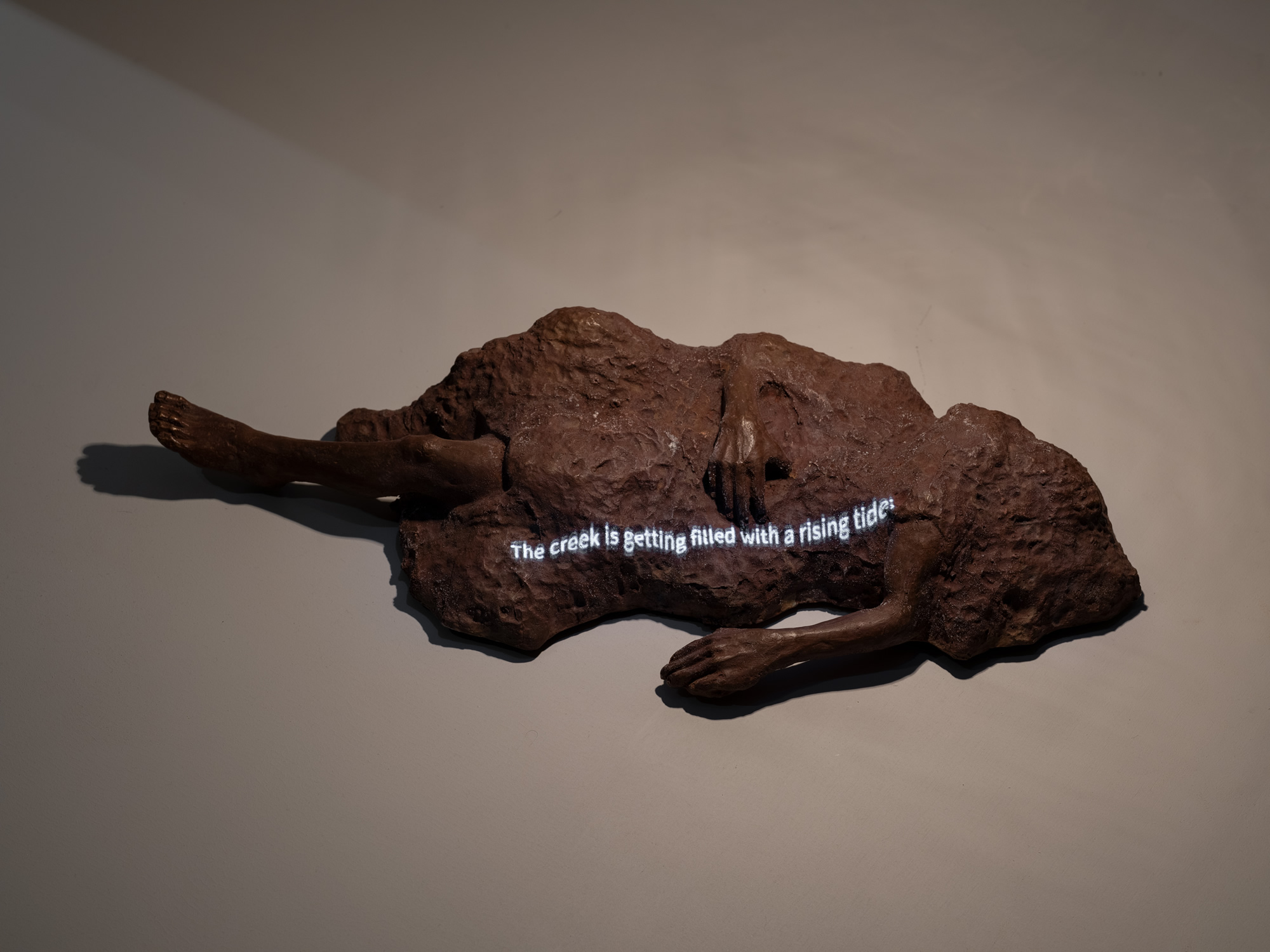

“This performance memorialises my father’s friend, a sanitation worker, who moved on skates, a broom in hand and a radio at his waist, while sweeping the street, every day,” says Patil. “The act of listening to music is an individual protest against social injustice and alienation.” Now, when powada performance at public places is prohibited by the state, Patil’s works serve as a counter-memory and archive. His bronze sculptures portraying collated hands, misshapen bodies, faces with multiple pairs of eyes, in tandem with spoken and projected poetry fill the gallery space with oracular sounds and stories. The face with numerous pairs of eyes, his signature motif, recalls the famous Dalit poet Namdeo Dhasal’s lines, “The living spirit looking out/of hundreds of thousands of sad, pitiful eyes/Has shaken me,” (trans. by Dilip Chitre) whose poem ‘Cruelty’ Patil projects on bronze sculptures in the series The Shadow of Lustre (2024). The poem begins with the line, “I am a venereal sore in the private part of language…”

Mithu Sen treats language as an unnecessary nuisance. If poetry is the act of expressing, meaning-making and thinking through language, Mithu Sen subverts the rules of language and poetic norms to make ‘un-poetry’. In I am a poet (2013-14), an installation-performance piece, Sen displayed a book consisting of computer-generated, unreadable text. Readers were encouraged to embrace “nonsense as resistance” and formulate a secret, dream language stemming from the subconscious. The unintelligible utterances communicated through sound, expressive intensity and interplay of textured words and silence. To further her project of spreading lingual anarchy, in 2014 Sen collected rejected poetry manuscripts of aspiring poets in Bangladesh and made an installation titled Batil-Kobitaloi [Poems Declined] (2014) with 1800 rejected poems and created painted artworks based on the typographical marks and edits found on the rejected manuscripts, such as cross-outs and editor’s notes. From castaways these books are salvaged as carriers of artistic gestures.

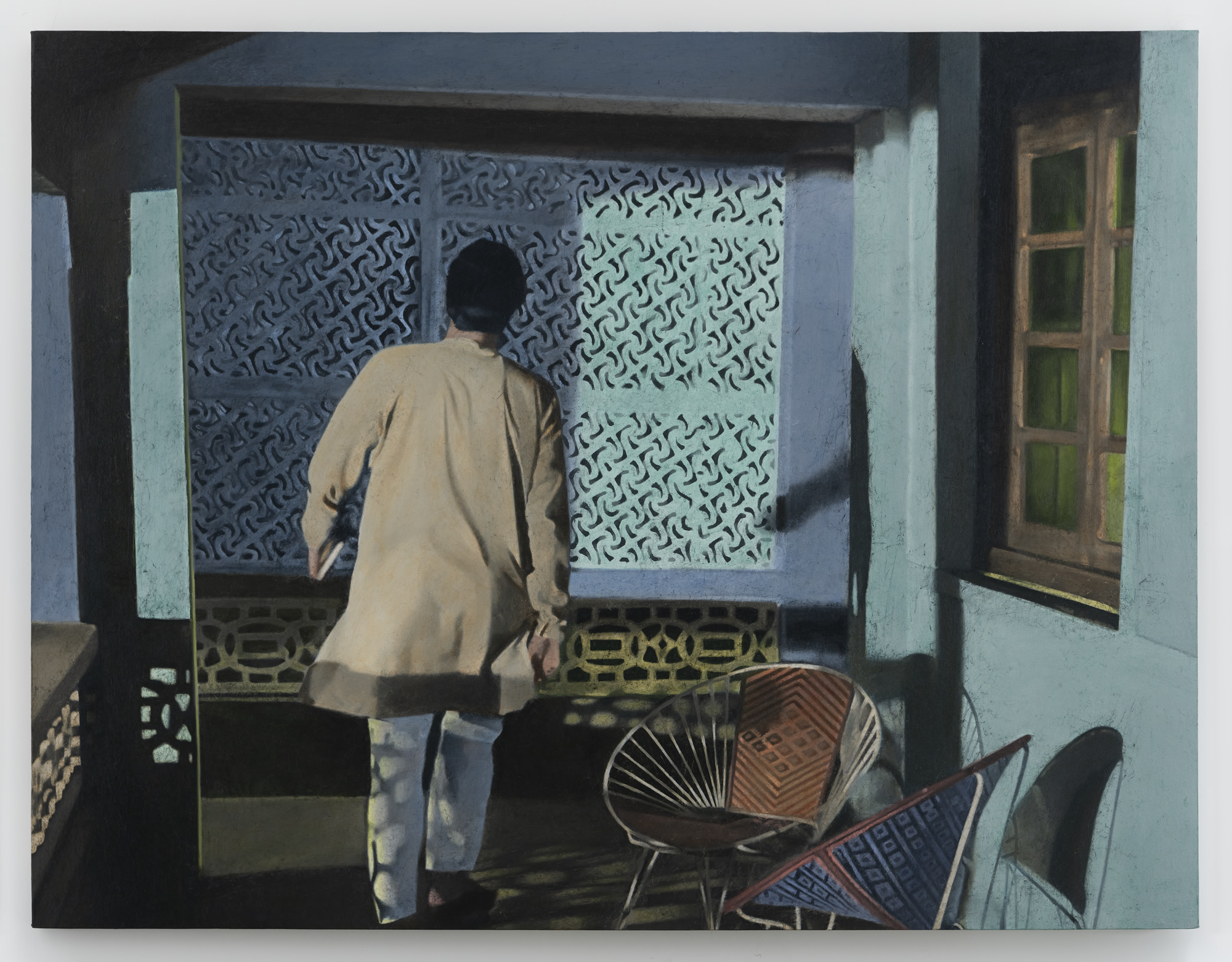

Poetry can be read as body language in Dodiya’s Anand with a book of poems (2020-2022). Looking at the protagonist’s resolute and unflappable gait, you feel as if a line or a stanza from the book of poems he is carrying has created a rustle of desire and reaffirmed a trajectory of thought. This is a painting of a film still from Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s iconic film Anand. By featuring the backs of film stars in the series Dr. Banerjee in Dr. Kulkarni’s Nursing Home and other paintings (2020-2022), Dodiya relieves stars from the baggage of hyper-recognition and their backs become blank screens for projection of anonymous fantasies. Decontextualized from the filmic narrative, these film-stills evoke their own account. The man can even be Dodiya (or any of the artists discussed above) who perhaps after reading a poetry collection, has come to the aesthetic realisation that poems can be painted.