Photography as a medium is often tied to the act of witness. Photographs become conduits of memory, or reminders of the places we inhabit or carry within us. While photographs are about recording that which is ‘seen’, they gesture towards the unseen, the locus and the lacuna. It is the unseen, overlooked, and undocumented events and territories that unfold in the works of contemporary artist Sarker Protick, hailing from Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Ruminations on space and time form the kernel of the visual lyricism in Jirno (জীর্ণ) / Spaces of Separation. Jirno is an ongoing photographic series by Protick, that was first exhibited as part of the larger Nirobodhi (নিরবধি) / Till Time Stands Still solo exhibition at the Shrine Empire Gallery, New Delhi, in 2022. It is also one of the larger frameworks in which one is drawn to situate the evolution of his work.

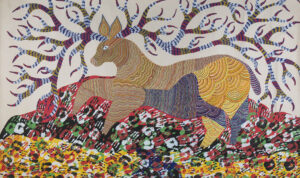

The dream-like, long exposure, black and white compositions, revealing architectural ruins of abandoned feudal estates, belonged to Hindu landlords in East Bengal. When Bengal was divided along religious lines, after independence from British rule, this minority aristocratic class migrated from what was then East Pakistan to West Bengal, India. The thick foliage in the photographs thrusts out of the cracks of the disintegrating walls and takes over the tombs, mansions, and havelis. There is a sense of slow subversion of the aesthetics fostered by the imperial gaze. The meditative mood in these images of ruins and relics invites nuance, not nostalgia.

The images anchor the viewer, not through a single “decisive moment” but through their sequentiality – a mode attuned to holding space for absences, erasures, and silences that linger beyond colonial legacies. The Partition of the Bengal region in 1947, in the aftermath of the fall of the British Empire, has faded from public memory in Bangladesh, whose creation during the Liberation War of 1971 left deeper scars. Today, the young nation stands on the brink of a new era, in the aftermath of a youth uprising, where more than a thousand youth protestors died in extra-judicial killings. In light of these recent events, the photographs take on a different meaning, one where the only thing constant throughout the passage of time is the shifting dynamics of power and the persistence of nature, manifesting with an Ozymandian hubris.

The “picturesque” quality of the image of the disintegrating edifice of a “samadhi” or tomb of a Hindu Zamindar’s wife in Gopalganj, Bangladesh, reminds me of British photographer Samuel Bourne’s surveying pictorial vocabulary and its attempts to lay claim to foreign landscapes. In his images of antiquated architectural ruins in India, Bourne created a fantasy of India—an unfamiliar land which had the potential to be civilised, controlled, and consumed since the colony was a place stuck in time, whose glories were a thing of the past.

This inherent metafictionality in Protick’s engagement with photography is especially prominent in Mr and Mrs Das (জন ও প্রভার গল্প), a story about his grandparents, where images of photographs hanging on a wall, displayed on a table, or stamped on identity cards become an integral part of a personal narrative tracing family history. This aspect of his work, where even single photographs hold multiple meanings, evokes what Edward Said called “contrapuntal” interpretation, a reference to music where multiple melodies co-exist independently- a fitting analogy, given Protick’s initial foray into music before turning to photography. Protick is commenting on the very act of image-making through his images.

In 2024, Protick won the ‘After Nature. Ulrike Crespo Photography Prize’ for his research-based photography project Awngar. The title refers to the burning embers of coal and investigates the fault lines in a society that revolves around a fossil fuel economy. It was his exploration of the connection between the expansion of the railways in British India and its role in the setting up of the coal industry that began in the nineteenth century that led me to his work.

I met Protick a year ago, when he was in my hometown, Dhanbad, for a short visit to photograph its coal mines. It was an interesting introduction to a photographer’s work through a peek into their practice. I was fascinated with not only the themes that he explores through photography but the continuing engagement in his work, quite akin to riyāz, another connection with his musical background.

In the text accompanying the publication produced as part of the project, Sria Chatterjee situates the photographs of one of India’s oldest mines, Narayankuri in the Raniganj coalfield, “Protick’s Narayankuri photographs run the risk of aestheticising an extractive sublime, but the research-led thoroughness of the project makes visible the material conditions that undergird the histories of resource extraction, production, consumption, and markets.”

While the visual narrative in Awngar explores the history of mining in the larger Bengal region, it does away with the usual tropes of hyper-sensationalising the suffering of mining communities or framing them in a way that reduces them to just labouring bodies. Instead, there are only two human figures in Awngar, more precisely two female figures. One, a wide-angle shot of an expansive landscape, engulfing a minuscule saree-clad frame. The picturesque aesthetic is the most prominent here, in its use of the human figure to offer a sense of scale, much like Bourne’s photographs.

It is the other photograph, of a girl standing by the railway tracks in small-town West Bengal, with alta or the traditional red tint on her feet. It became what Barthes called the “punctum”, or the incidental detail of a photograph that pierces the subjective and private perception of a viewer. It had me transfixed. I could almost feel myself slipping beside her, waiting for a train like I had a million times before all my life. And thus, the work of an artist from the other side of the border suddenly spoke to me in a way that laid bare the absurdity of our hyper-nationalist zeitgeist.

We returned to the question of ‘time’ and ‘space’, as we chatted over a phone call recently. I asked him how time became a part of his process. Protick replied, “From the very beginning, I was partial to long-form works. In the works or stories that I felt strongly about, time always played an important role… I believe, there is a different kind of impact produced by long-term projects.” He describes his relationship with a topic, or “bishoy” as he called it (we spoke in Bangla), in the way one feels an attachment with their cat, friend or a family member. “Sansar korar moton,” he explains, which can be translated as “managing a household.” In Bangla, the word “sansar” refers to both the universal and the domestic.

The influence of Bangla language and literature in his work is also another facet that speaks to this moment in time. During our visit to the Bastacola mines in Dhanbad, Protick recalled reading the memoir of a friend’s relative, Akash Patal Jol Jangal by Birendranath Mukhopadhyay, a Mines Safety Officer who worked in Amlabad colliery, located in the Eastern Jharia Area of BCCL, a subsidiary of Coal India Ltd, during the 1950s. As I heard him narrate a spine-chilling incident, where Mukherjee had to wander around the underground mine a whole night to locate the body of a miner who died in a deadly accident, so that his family could claim compensation, I wondered about the paucity of such first-person narratives, foregrounding the complex industrial heritage of the region. Protick says that the book has a latent influence on his work.

In India, a crackdown on Bengali citizens, especially the targeting of migrants and Muslims, has weaponised hate to threaten the lives of a people whose stake in a homeland is dictated by barbed borders and bigoted bureaucracy. At the same time, India is sheltering the ousted former Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, allegedly accused of siphoning billions from Bangladesh. The recent political tensions between the two countries have also led to the termination of the collaboration agreement by the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, severing ties with the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dhaka, where Protick has studied and now teaches.

When asked how these hostilities would affect cross-border creative works like Awngar, Protick observed that they are not only making things difficult for artists (citing his own experience in securing a visa), but also having a detrimental effect on the economy, impeding medical visits, business trips, and tourism.

In his latest work, Akash Kalo Megh (Shadows in the Sky), Protick’s camera zooms into a single place, the locality where he has spent his entire life. Close-up silhouettes of crows, whom Protick calls “the iconic birds of Dhaka,” while reminiscent of Masahisa Fukase’s Solitude of Ravens, here, invoke sentient creatures surviving amidst the high-rises in the concrete jungle of the city. His wife, Sara, makes a few appearances, or as Protick candidly calls it, “her cameos.” During our conversations, Protick spoke about photographing his mother, Bina, as an attempt to document the life after retirement for an ageing single woman on her own, in a city like Dhaka, which is not often talked about.

We live in a time, inundated with images, livestreamed from war-torn lands or deep fields of distant galaxies. The capitalist machinery has infiltrated how we envision time. We spend, invest, and save time. Time is currency, in an economic structure that has alienated labour and leisure into commodities, entangling individuals and institutions into a system that knows only one master, the logic of the market. Our waterways, landscapes, and fleeting human lives are enmeshed in these supra-systems of power. Sarker Protick’s photographic practice is situated within these realities while weaving in the elemental forces of nature and the anthropocentric hubris of civilisations. The lens, in his hands, becomes a tool to look back at the rise and fall of regimes and empires, or an aging couple in the confines of a single apartment—a bridge between the everyday and the eternal.