‘In the history of art late works are the catastrophes.’

-T W Adorno, “Late Style in Beethoven”, Essays on Music, (2002) p. 567

ہمیشہ دیر کر دیتا ہوں میں ہر کام کرنے میں

ضروری بات کہنی ہو کوئی وعدہ نبھانا ہو

اسے آواز دینی ہو اسے واپس بلانا ہو

ہمیشہ دیر کر دیتا ہوں میں

Hamesha der kar detā huñ maiñ

zarūrī baat kahnī ho koī vaada nibhānā ho

use āvāz denī ho use vāpas bulānā ho

hamesha der kar detā hun main

-Munir Niazi, Hamesha der kar detā huñ main, Rekhta.org

I.

It’s not like ripe fruit—succulent and full of promise—but how Adorno opens his description of Beethoven’s later works could pass for rotting states. Bitter. Furrowed. Spiny. Wrung out of form by time, showing “more traces of history than of growth” (Adorno: 2002, 564). It is remarkable that Adorno begins this discussion on musical form and transformations in style with a visual, even tactile, analogy of entropy, as if imploring the reader to understand that there is a different frame of sensing at work here, a frame that is as natural as the state of a fruit that lingers beyond the hour of being devoured. Some trick has been played, and marks of time’s passage and pastness, the congealment of folds and crookedness of contours, overpower the sense of its interim state of vitality. The fruit is now adrift, not beholden to any teleology of function or pleasure. It is simply too late to take a bite.

But a bite is taken when Edward Said considers what emerges in the event of lateness. For Said, late style, read here like Adorno through the lens of biography as works made towards the end of a creative life, is still a fertile ground for a renegotiation of artistic truth. Works made in the late period, skirted by many minor endings, and the growing certainty of demise, inaugurate new relationships with artistic form and purpose. Lateness, for Said, provides the artist with the opportunity to cede attempts at ‘ongoingness’—the crafting of a signature scheme, the cogency of a compositional system, the sustenance of a continuity. All of the makings of a recognisable style—repetition, recurrence, resonance, reflection—can now, in confronting the period mark of mortality, be abandoned. Adorno considers this as a freedom from subjectivity, begetting an art that is not addressed to the world but produced from a place of “splintering” and fragmentation, and the loss of totality – or the project of keeping things whole. For Said, this is akin to a form of self-imposed exile—from previous aims and pursuits, from participation in the world in direct ways. Late works for Adorno and Said, are ruled by the negative—they are unresolved and partial, haunted by silences and absences, dissonance and disarray, fissures and intransigence (Said: 2006, 16). These works are punctured by an unruly tension which exerts a pressure on its form; consider the strain of the final word of Adorno’s essay—catastrophe. Picking up this thread, Said argues that lateness can be detached from the aspect of aging and be understood through the various shapes of exile, the experience of which marks a break in the flow of time from the point of separation, and contains within a single word the glare of disruption, departure, dislocation, disjointedness, detour, divergence, distance, despair, estrangement, alienation, doubling, contradiction, renewal and return. To Said, lateness can be read as a rupture in the fabric of time, an exit from its ordinary proceedings. Said conceptualises lateness as a method that entails a refusal of synthesis, and I extend this to include the deferring of conclusions, the subversion of stylistic apotheosis, and the defiance within the work of any attempts to systematise its elements.

Lateness marks a fundamental separation from timeliness. Yet, reading Adorno and Said’s essays on lateness, I can’t help but detect a splitting of the word’s meaning in its transfer from one theorist to another. In these essays, ‘late’ reads alternatively as a view from the state of entropy and the arrhythmic clock of exile. Late is implied both as the generative disorder of a life closer to its end and the indefinite interregnum, the temporal “rip” of displacement—both the final hours and the frozen hours.

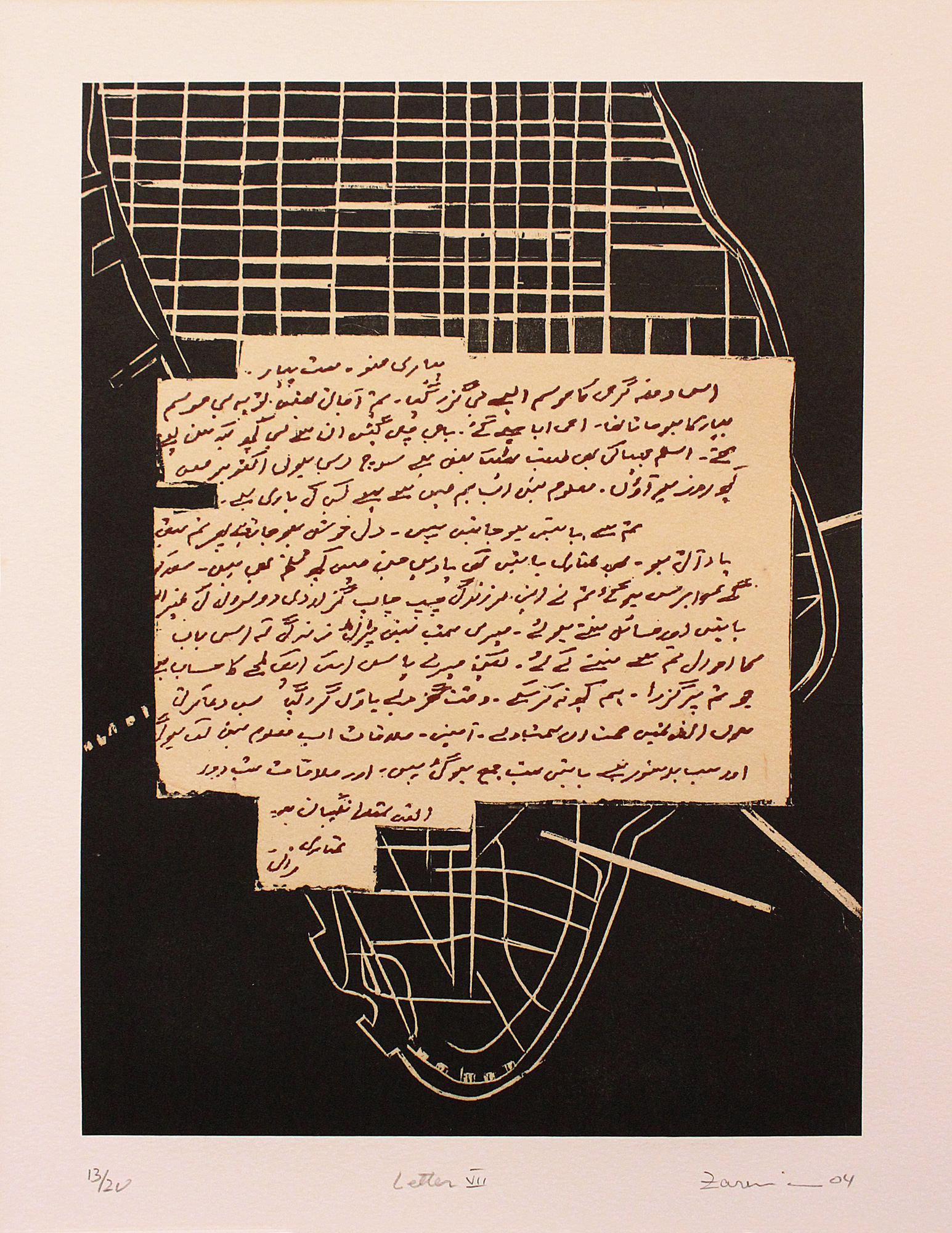

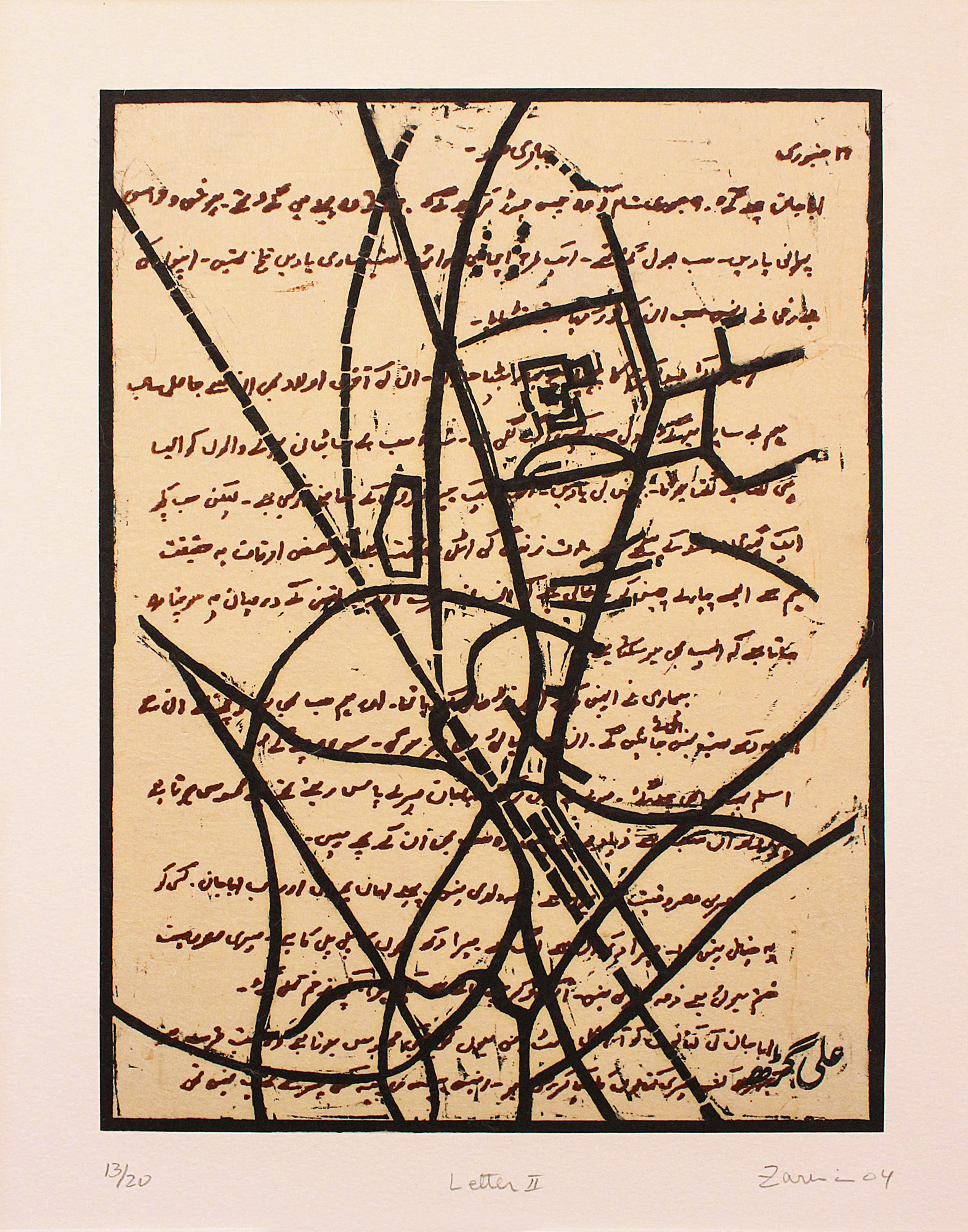

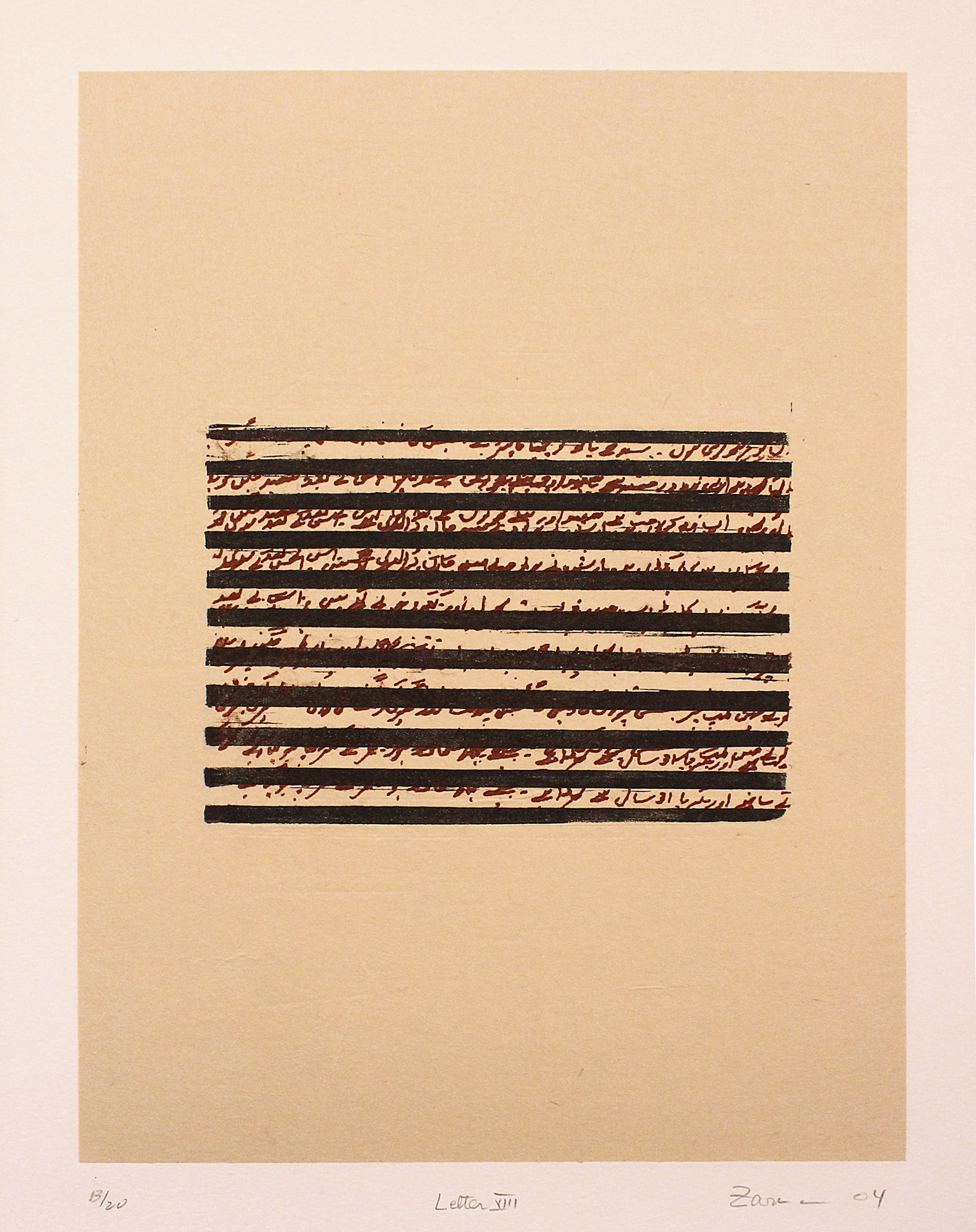

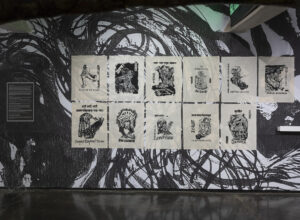

To exist at a slant in relation to time, to bear the pricks of delayed missives and unfinished stories, to feel the weight of the political press upon the intimate—is conveyed with a poignant clarity, a clear view into bleakness in the series Letters from Home (2008) by Zarina. Unlike her other works which confront the public visualities of the Partition directly, Letters from Home adopts an oblique approach. In the series, Zarina excerpts lines from her correspondence with Rani, her sister who was then based in Pakistan. The excerpted text carries the voice of Rani, often interrupted with lines that chart the maps of cities, the blueprints of homes, or lines that simply redact entire sentences. The texts allude to loss, transformation, separation as experiences that Rani has undergone, which includes the absence of Zarina. Vast tracts of their lives are compressed into a finite number of prints that tilt towards illegibility. Incomplete and fragmented, these letters become echoes on paper—trailing faintly under the armatures of borders, fragile belongings and impossible crossings. Our access to the letters is partial and mediated, we can only be imperfect witnesses to this impassable distance between the sisters and our shared histories. A late hour has descended.

II.

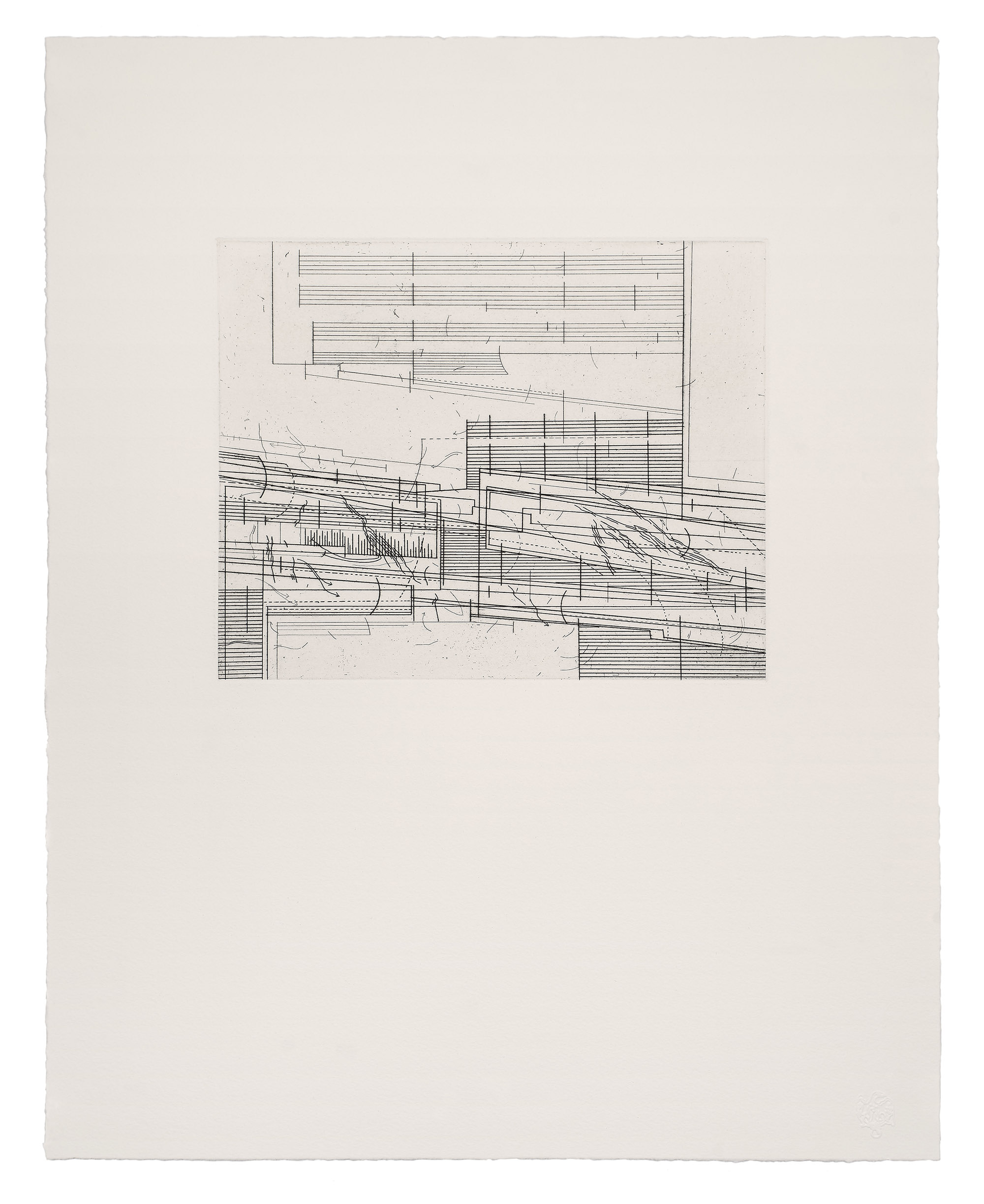

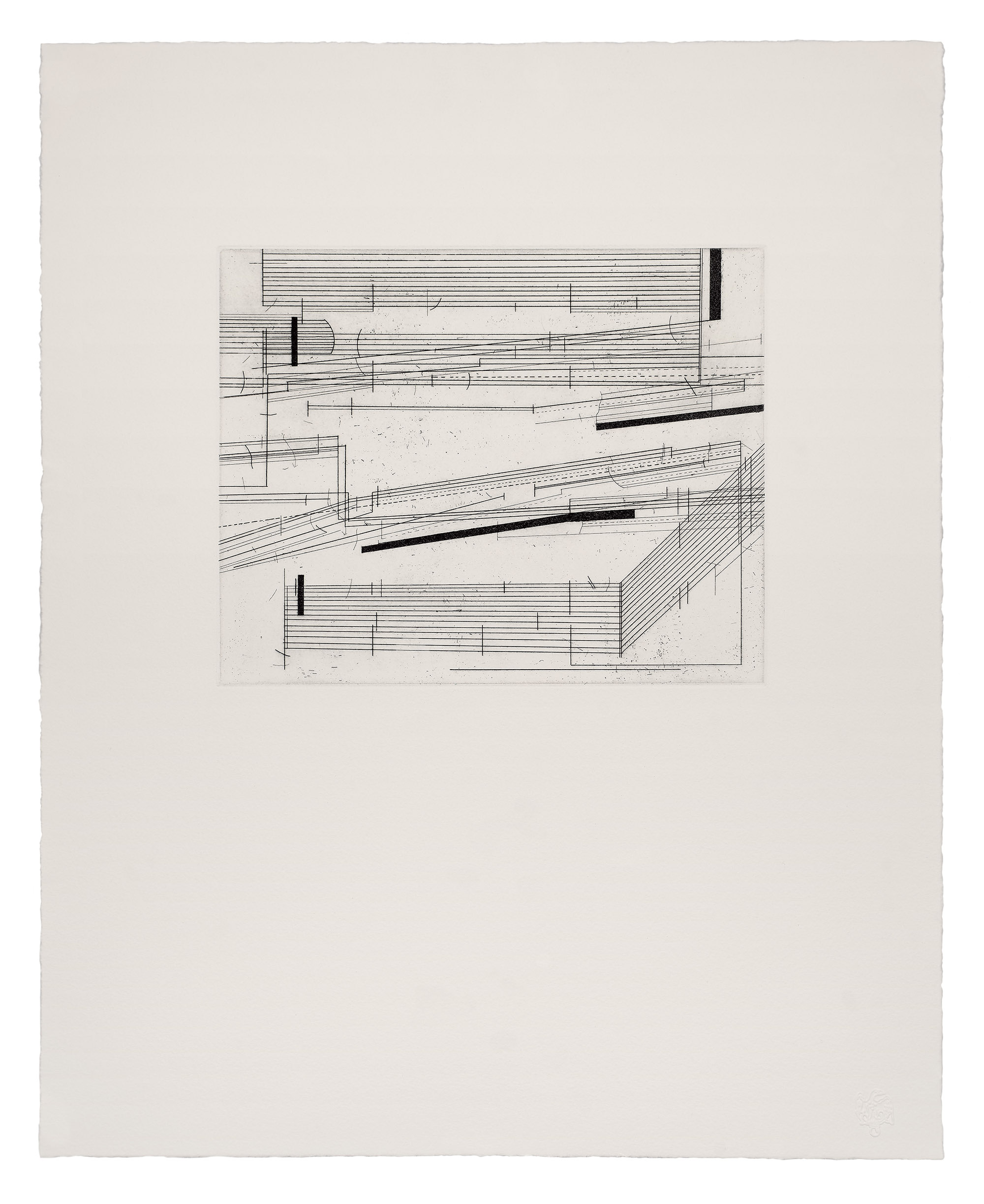

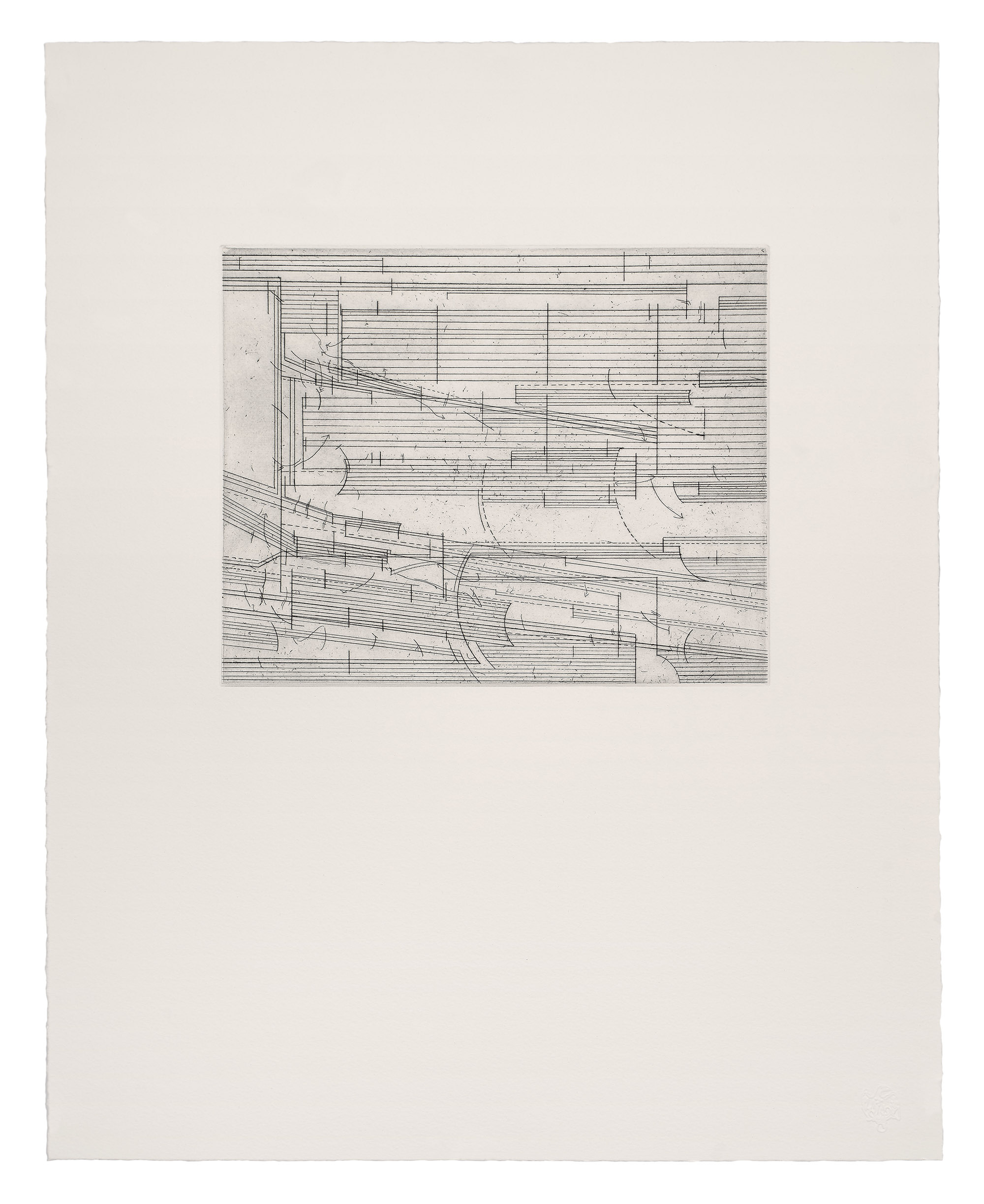

Though tinged with the quality of lateness, it is neither early nor late—but rests somewhere in the middle. Seher Shah’s Ruined Score (2020) sits uneasily with other works in the corpus. The etchings sustain the monochromatic intensity of her practice, where the solidity of ink is girded to the appearance of lines, and there is a commitment to discovering the dialectics of printmaking as medium, matter and process. But beyond this, it is an itinerant work, orbiting alongside – but distinct from – the other works Shah has developed that are overt explorations of modernist legacies and socio-political anxieties in South Asia.

Ruined Score is not a straightforward work, in fact its beginnings lie in negation. At first the etchings appear to resemble the form of staves, but there are no notations and the sections are irregular and far too many. While recalling the structure of sheet music which hosts notes and time signatures, the forms in Ruined Score signify other terrains. Perhaps these are traces of concrete palimpsests, outlines of the dense urban environments of Karachi and Delhi, two cities that exert themselves upon Shah’s enquiries, appearing with an underlying unease as home, subject, interlocutor, and foil. Conventional notations rarely appear, and if they do, are driven by errancy and overpowered by a Dickensenian carnival of marks, arrows, vertical punctuations, scratches, slanted hyphens, and the smudgy traces of the printmaking process, as hazy remnants of contact and imprint. The title suggests a preceding moment of deformity—the score is ruined; it is difficult to extricate from this devolved state what may once have been perfectly ripened sound. We are not witness to the process of ruination but we inherit its aftermath.

But what marks this ruining within the score? Is it the defiant staves, arbitrarily transecting each other to produce the visual experience of loudness, of sonic blur, of cacophony? Drawing from Shah’s architectural eye, these prints suggest the incoherence of our packed, built worlds, one dense mass of buildings pressing into another. Amidst the suffocating lack of space, precarious proximities, and archipelagos of capital, a fragile commons is lit ablaze by the high octave pitch of ethnonationalist loudspeakers. The work doesn’t attempt to rehabilitate any of these interpretive possibilities, and if anything, suggests the fundamental discordance at the heart of the modernist imaginary; rupturing its false claims to universality by taking the scaffolding of a language and distorting it into incoherence. Its most potent gesture is to absent all the notational symbols, vacating the prints of the very hinges which hold the language of music—the staves, lacking any notes, are both empty and transformed, closer to resembling tangled electrical wires, erratic blueprints, rough outlines of an urban horizon.

Ruined Score holds all this and more—and offers no synthesis, asking us to dwell in the tensions of this multiplicity, to follow its warbled cartographies. It is asking us to proceed without a compass.

III.

Despite being a prolific public figure, Lala Rukh is a difficult artist to approximate. This is due to the fact that the documentation, archiving and display, of chapters from her remarkable life and its artistic and textual corpus have only begun to be taken seriously in the recent decade, appearing irregularly as exhibitions and surveys. And in the coda of her works, an even more difficult series to approximate is the drawings that form Hieroglyphics, in which calligraphy transforms letters and words into symbols and imagistic forms. The drawings in Hieroglyphics prise open the vicissitudes of language and image— the lexicon of text, often citational, merges into the economy of calligraphic mark-making, carefully measured by Lala Rukh in qat—the flat part of the pen’s nib that transfers the ink to the page and serves as a unit of proportioning the length and width of letters (Lala Rukh and Lookman: 2003). One drawing in particular from the series, speaks to lateness through the dim possibility of return and reunion. Hieroglyphics I: Koi ashiq kisi mehbooba is a deceptively simple ink drawing—just one line, unfolding right to left, and speaking to Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s haunting poem. The poem imagines a moment in the future—both possible and not-yet, where estranged lovers may cross paths. Faiz’s nazm is a tender petition to the once-lover: to stop and share a moment. As you would sit with a stranger, he writes. Faiz is requesting his past lover to adjust the aperture of memory—to both remember and forget; to suspend the grasp of grievances just enough to linger; to not taint the moment of reunion with complaint. The pain of loss will be felt afterwards, sharper in the shadow of the second parting. This nazm complicates the moment of reunion or return, just as exile brackets the idea of home. Lateness disturbs the fixed coordinates of time, and the instance of the meeting of estranged lovers is always, already too late.

I have often wondered why Lala Rukh inked only the title of the nazm, which proposes an act of addressal—a lover to his beloved—but chose to leave out the substance of this plea. Perhaps because the nazm also acknowledges that in the event of this meeting, much will remain unspoken between the lovers, each act of speech is besieged by that which cannot be said. Further, Faiz lists the things that must not be uttered, for they compress too great an intensity—no past declarations of love and no recriminations must be brought to the fore. In fact, much of the nazm forecloses the possibility of any speech—Faiz is certain there will be eyes brimming with tears or reproach, but speech remains conditional; the lover may choose to acknowledge these gestures, and may choose to speak or not. And so, all of this, every line of the nazm, sits on Lala Rukh’s drawing as the negative space, in the form of the silence that surrounds the letters; just as it is silence that trails the meeting of past lovers.

To read the nazm with Lala Rukh’s drawing then, is to understand that the title is the only verbal proposition in the nazm, whereas the remainder of the nazm is devoted to understanding what, if anything, can be said in the afterness of separation, when no word is innocent, and every breath bristles with memories. Perhaps all Faiz is suggesting is the sharing of a moment, and the blankness of Lala Rukh’s drawing presents such a clearing—offering a space for the lovers to pause.

To read the nazm as it is distilled in Lala Rukh’s drawing, to its barest essence, is to understand the impossibilities birthed in lateness, for if a once-lover meets his once-beloved—