What is the significance of the art world in constituting “folk art” practices? Do art exhibitions and craft melas serve as contact zones where different ‘cultures’ meet and interact as equals or is there a hierarchical relationship whereby the values of the art world serve to legitimise a pre-existing canon according to which the folk arts are evaluated and judged as art?

Historically art worlds come into being when art acquires an autonomous status separate from religion or any other social institution. In terms of this perspective then it becomes important for a sociologist to ask which of the folk arts in India can actually be defined as ‘art’ – those which allow themselves to be detached from the wider social context in which they were performed perhaps? It is important to note here that I use the rubric of ‘folk art’ to include adivasi or tribal art as well since there is very little difference in the forms of production and values ascribed to them. The Pardhan-Gonds are classified officially as a scheduled tribe and the artists that I have worked with all live in Madhya Pradesh. I will address these questions through an examination of the Pardhan-Gond style of painting.

Exhibition Spaces and Encounters with Alterity

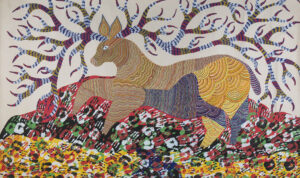

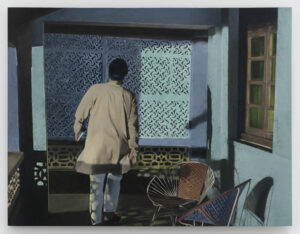

My first encounter with Pardhan-Gond art was at an exhibition organized by the artist J. Swaminathan in New Delhi in the late 1970s when I was a Master’s student in sociology. (I prefer to use the hyphenated term ‘Pardhan-Gond’ rather than Gond to refer to this art style because all the artists belong to the Pardhan segment of the Gond adivasi formation).The bold colours and abstract designs of the paintings were strikingly reminiscent of the artwork I had been exposed to while reading anthropological works on the aboriginal arts of Australia and the Americas but I found the exhibition as a whole somewhat enigmatic. There were no explanatory notes or attempts at contextualisation that would help in making these compositions intelligible. It was only later when I started researching the folk arts that I realized the modernist framing of what I had seen – not just the artworks themselves but also the way in which they had been exhibited with a minimum of textual information to guide the viewing public. Let me now fast forward to the next major exhibition of Pardhan-Gond art in Delh in 2006- held at the prestigious Lalit Kala Akademi, titled Jangarh Kalam (School of Jangarh), after Jangarh Singh Shyam, the acknowledged founder of the Pardhan-Gond style of painting. Unlike other exhibitions on regional art forms where the individual artists are largely unnamed here there was an open acknowledgement of the agency of the artist and his role in actually founding a new style of painting similar to the ways in which the contributions of avant-garde artists such as Andy Warhol or Marcel Duchamp are presented. The exhibition catalogue and art book released to mark this event gave comprehensive accounts of the artists whose works were being exhibited including details of previous exhibitions of their work and an overview of the style’s developmental trajectory; special features on Jangarh Singh Shyam; and the seminal contributions of Bhopal’s Bharat Bhawan and Swaminathan in ‘discovering’ him and fostering this new ‘folk art’ (Vivek, Jaya, Jangarh Kalam: An Exhibition of Gond Paintings, 2006).

What do these two exhibitions tell us about this art form and are the differences in their curatorial modes significant? The 1970s exhibition organised by Swaminathan himself seemed to have been framed as a kind of avant-garde encounter with the unfamiliar. Central to the staging of the unfamiliar, according to this perspective, is an aesthetic experience based on an unmediated encounter. The authenticity of the aesthetic experience is premised on the very fact of incomprehension. The viewing public could only look – they did not need textual exegesis to appreciate this art (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1995). “Primitivism’, the movement and ideology that underpins this view of authenticity, was extremely influential in the early part of the 20th century when ‘artifacts’ from non-Western societies found their way into the museums and markets of Europe and America. Artists were inspired by their abstract forms to produce works that shunned mimetic relations with ‘reality’, works that conveyed intense emotion precisely because they were freed from having to imitate appearance. The movement itself was short lived but its impact was felt globally and continues to inform ways in which folk art is represented in many parts of the world.

Jangarh Kalam, the 2006 exhibition, assumed a greater familiarity with the Pardhan-Gond style. The inclusion in the catalogue of the artists’ bio-sketches as well as a detailed genealogical chart testified to its crystallisation as a community based art form, albeit a hybrid one – a feature that the artists are aware of. Noting the distinctive all-over design used by each artist to decorate his/ her figures I remarked that the design seemed to function as a personal signature – a feature I had not noticed in other folk styles. Anand Singh Shyam, Jangarh’s cousin, to whom I had addressed these remarks responded by saying that it was city people like me, prospective buyers of their artworks, who were responsible for the evolution of these design signatures. “Jangarh insisted that we all choose unique motifs that would identity our paintings as uniquely ours rather than that of some other artist,” he said. Exposed to ‘world art’ from an early age due to his ongoing interactions with Swaminathan and other artists at Bharat Bhawan, Jangarh understood that the art market placed a premium on individual creativity. Jangarh was employed by Bharat Bhawan. An extremely sensitive artist he used this opportunity to familiarize himself with different techniques and with the work of internationally renowned artists many of whom visited Bharat Bhawan from time to time and whose work were displayed in the Rupankar gallery at Bharat Bhawan (Chatterji 2012).

Unlike the ‘traditional’ folk arts the Pardhan-Gond style developed through the interactions of Pardhan-Gond artists with modern art institutions. Overtime, it developed into a community style as Jangarh invited his relatives to assist him in his painting. A traditional mode of learning through apprenticeship by copying the work of master artists co-exists with the aesthetic values of the art world making this a hybrid art form that is articulated in terms of the ‘vernacular modern’ in the discourse of the art world in India (Chatterji 2012).

Commodity Production and the Making of Folk Art

The philosopher Arthur Danto coined the term ‘art world’ to capture the art theories and history that shape exhibition practices, institutions and discourses that help identify and even define a work as art. Historically art worlds come into being when art acquires an autonomous status separate from religion or any other social institution. The folk arts, traditionally, were not thought of as autonomous fields of artistic production but as part of ritual practice or everyday utilitarian work. For some cultural practices to be considered ‘art’ they must be separated from the contexts in which they were embedded and assimilated into new contexts articulated by the art world. While art critics and exhibition curators celebrate the changes taking place in the art world that enables historical revisions in the very definition of the art object there is relatively little attention given to the changes in the field of cultural production as artifacts are detached from their conventional contexts and acquire new kinds of aesthetic value much less on the changes in the objects themselves (Danto 1964, 1988).

The ‘commodity phase’ of artifacts that have been absorbed into the margins of the art world has led to significant changes in cultural production as the makers of these artifacts grapple with contrary demands of novelty and singularisation required by the art world and the traditional craft ideal of collective creativity (Kopytof 1986). The Pardhan-Gonds are a branch of the Gond tribal formation and have traditionally served as bards for the wider community of Gonds. As memorialists for their patron Gonds the bards kept their myths and legends alive through their epic narratives. While the performance tradition had declined over the years artists such as Jangarh and his relatives, inheritors of this rich narrative repertoire, were able to translate themes from this repertoire into visual images.

Primitivism, Abstraction and Pardhan-Gond Art

What are the significant features of Pardhan-Gond art practices that led to the recognition of their murals as art rather than merely as wall decorations? An obvious answer might be their transference from walls to paper and canvas that enabled their circulation as commodities. But as Danto (1988) persuasively argues artworks are distinguished from artifacts by their latent properties that will reveal themselves later through modes of consciousness that their contemporaries have yet to acquire.

Pardhan-Gond art evolved in the precincts of Bharat Bhawan, a multi-art centre established by the government of Madhya Pradesh in Bhopal. J.Swaminathan, a famous modernist artist, was given the charge of establishing its art collection. Deeply influenced by the ‘primitivist’ movement in modern art Swaminathan turned to the folk arts of Madhya Pradesh for their abstract and numinous quality. Modern artists began to seek inspiration from the arts of so-called ‘primitive’ people from the beginning of the 20th century. Turning their backs on representational verisimilitude, they sought to make artworks that embodied emotional intensity much like the masks and ‘idols’ from Africa and Oceania. To be primitivist was to strive for a universal abstraction and freedom from appearance (Severi 2020). For Swaminathan (1995) the Pardhan-Gond artists achieved a kind of ‘psychic numen’ through the ‘colour geometry’ of their compositions thus creating a parallel reality through their art. It is not clear what exactly Swaminathan meant by ‘colour geometry’ but he was deeply impressed by the way Jangarh used primary colours which he said created a feeling of an inner meditative space (Swaminathan 1995: 49). Their preference for abstraction did not stem from an inability to represent reality but was based on a deliberate choice. Thus even when Jangarh introduced figures from our phenomenal world into his compositions they did not represent physical reality but were symbols of the human psyche, Swaminathan said.

Jangarh responded to modernist ways of looking by making his paintings self-explanatory. He tapped into the narrative repertoire that was part of his heritage but was careful not to refer directly to concrete myths and stories that were unfamiliar to urban viewers of his paintings. Thus, his paintings suggested a timelessness and spirituality that could appeal to their sensibility while simultaneously being detached from the narratives themselves, a feature that has become an established attribute of Pardhan-Gond art and may be the primary reason behind its ready assimilation by the art world compared to other art forms that are embedded in ritual complexes such as the Pithora art of the Bhils or the scroll paintings of the Chitrakars of West Bengal possible due to their being embedded in local contexts of ritual and narrative performance. At present Pardhan-Gond art is in a somewhat liminal position. As a folk art form, it emerged in the 1980s in the precinct of Bharat Bhawan. Artists are trained in a traditional form of apprenticeship but some like Jangarh are grouped along with other contemporary Indian artists such as Paresh Maity and Subodh Gupta by the art world. It is interesting to note that Jangarh was ranked among the five highest performing contemporary artists for the financial year 2024-25 with prices ranging from USD 57.5 lakhs to USD 2.15 crores by the Indian art market report published by Asign Data Sciences. No other ‘folk’ artist has been able to achieve these prices in India.