…each time the world she paints is new

(Excerpted from So Long, Tom; The Poetly Newsletter)

My encounter with visual art grew from an affinity with sound – the deep more-than-human alāp of dhrupad music gave birth to ways of apprehending and finding resonance with the visual world. The long, undulating mīnds of alāp formed a parallel syntax of colour, rhythm, shape and performance. My Ustād – Zia Fariduddin Dāgar – explained to me one day, the meaning of remaking the world, each time we create. After an inspired class at our gurukul in Palaspe, Mumbai, I asked him about tradition and ‘difference’: “When we sing, it must be such that a stranger walking on the road should be arrested in their tracks, by the unexpected music that reaches their ears. The same voice that speaks, can create magic. Every time I sing a rāg it must be different. Every experience is different – so how can two bihāgs ever be the same?”

Ustād was gesturing towards the creation of a “space” of art-making, that is ever-evolving, in medias res, always in the process of becoming. It is difficult to capture this space – to articulate its force through language. It is always new. But what of the experience of art? What of the writer and the critic – what of the scholars who read meaning and feeling into the impulses of painters and poets, musicians and performers? How do we imagine that “space” of encounter? In a world that is caught between the impulses of the “market”, the “art critic”, and the rasik, there is no easy answer to this question.

The working space for an artist is an extension of the pictorial space, but also the “workshop”. Speaking about the conception of a “working space” the abstract artist and revolutionary thinker Frank Stella observes: “But, after all, the aim of art is to create space—space that is not compromised by decoration or illustration, space in which the subjects of painting can live.” That space is elusive, and its vanishing presence, today, is related to socio-political overwhelm, and rapid fragments of information assaulting our already diminished attention spans.

But the realisation hit me with the same force that the harmonic resonance of colour and form in a Raza painting frames the viewer’s surprised body, the way the bulging eyes and pierced, bleeding breast of a figure in a Caravaggio painting arrests the viewer who is caught in the corporeal fire of that painted moment. This magical “space” of engagement between the work of art, and the viewer is meaningful, and pervasive. It is replicated through writing – that contextualises the work through creative engagement that takes it beyond a simplistic fetishization as commodity. The work of art lives in the imagination of its muse – the writer.

We encounter a new working space, now and a new kind of artist – the poet, perhaps?

The poet finds feeling and substance by writing into the world – not by writing about it, in the way that a “critic” does. What does it mean, then, to move beyond familiar modes of scholarship, familiar ways of making meanings, towards a working space of creative engagement with a work of art? How can we write into the space of art, curating our efforts towards ‘listening’, and sensing, rather than imprisoning with meaning, the “critical” space of the artist, and the artwork? How to verb like a poet – how not to enclose sensation and feeling within the rigid contours of the noun?

ArteSpace was born out of these potent questions about form, with the vision of providing a space for the artisanal craft of writing that goes beyond “art” as it is understood. “Arte”, in the romance languages, etymologically refers to ”skill”, “craft”, or “art”. ‘Arte’ is also associated with the Ancient Greek ‘τέχνη’ (“techne”, again, meaning ‘skill, craft, art’). Heidegger says of “techne” that it “is the name not only for the activities and skills of the craftsman, but also for the arts of the mind and the fine arts.” But techne is also connected with “knowing” – an opening up, “revealing.” This is the kind of work the magazine hopes to give space to. In ‘Arte”, then, we find stories, artists, and artworks that reveal.

It is revelation that reveals, even art writing, as art. In aligning with the senses, with sensation, movement, and feeling ArteSpace, seeks a pursuit that is not at odds with “critical scholarship”, but a praxis that subverts its singular impulse towards argument. Writing into art, creatively, by locating the experience of self and spirit within the work of art – turns, even viewing, into an active exercise. It allows the work of art to become a social entity, contextualising it in the realm of democratic imagination, not the hubristic urge to control, or express power over the work of art.

The first edition of “stories” reflects this vision, bringing together an eclectic set of fresh voices that contextualise, and narrate art praxis through poetry, critical and creative commentary, and provocative scholarship.

Flower Gathering

anthology(n.) – anthos (Greek) “a flower” + logia “collection, collecting”

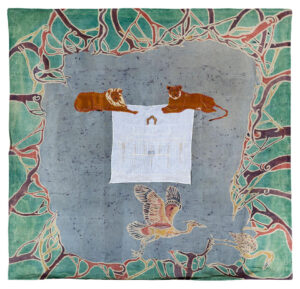

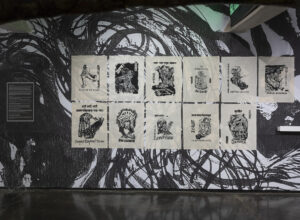

Artespace opens with Akash Bharadwaj’s The ‘Invisible’ Network: Galleries, Collectors, and Artists in India that traces a historical journey of contemporary Indian Art by exploring the different emergent centres of artistic exploration in the country. His essay contextualises the human element of “relationships” within the material institutions that dominate the scenario, today. Shweta Upadhyay’s Ways of Reading: Unravelling the Use of Poetry in Indian Contemporary Art casts a net that is both wide, and deep, while exploring Indian artists’ engagement with poetry. Sandra Elizabeth’s Saturated Waterscapes in Paula Sengupta’s Oeuvre explores artist Paula Sengupta’s intimate relationship with ecology, and more-than-human environments. Roma Chatterji’s The Making of Pardhan-Gond art looks at the formation of an epistemic and aesthetic category – problematising age-old labels of “folk” and “art”. Her study, enriched with personal anecdotes, foregrounds the question: “What is the significance of the art world in constituting “folk art” practices?” Kamayani Sharma’s Cantus Firmus: Notes on Listening to Jangarh Singh Shyam is a reflexive foray into the poetics of “listening” as method – within, and beyond the archive – articulating Jangarh Singh Shyam and his practice, harmonising “testimonies” of his life and work, with Shyam’s own voice and perspective. Imran Ali Khan’s Sitting Still: Reading Tanmoy Samanta’s Artworks, is a meditative exploration on time, space, and ‘object’ in Tanmoy Samanta’s layered compositions. In They are Always Working… Lina Vincent writes about the practice of Waswo X Waswo and the “cohesive wholeness”, in the labour and teamwork that has become a hallmark of the collective. Arushi Vats’s experimental essay Lateness as Method: Three Fragments on Music and Love takes a contemplative, less-traveled path through a forest alive with the works of Zarina, Seher Shah, and Lala Rukh. With poetry as companion, Theodor Adorno, and Edward Said as allies, Arushi leafs through the entanglements of “catastrophe” and “rupture”, “exile” and “love”. Poet Ajay Kumar’s series of poems, “after movement” writes creatively into “urban” artworks by artist Ashwin J Chandran from a series entitled “Movement of Madras”. These poems go beyond ekphrastic and “art-historical” modes, by deepening the “working space” shared by artist, artwork and poet-witness, in a silver chain of aesthetic comradeship. In Indigo: Sensorium of Colour, Handloom Futures, a research collective of artisans and historians of science, collectively documents the centuries old living tradition of fermentation dyeing and dye-making as experienced by the indigo dyers. In Paper Trails Ravikumar Kashi’s tender musings on the craft of “working with paper”, deftly threads a body of work, developed over decades, into an uneven but intricate tapestry of loss, belonging and vulnerability. In Time and Space: Sarker Protick’s Photographic Continuum, Sudeshna Rana journeys through the artist’s landscapes of light and loss that negotiate the shifting contours of history and intimacy, labour, life and livelihood. In Walking the labyrinth Avani Tandon Vieira speaks to Philippe Calia about the complex dynamic between photography and urbanity. Saranya Subramanian’s visceral engagement with Anupam Roy’s 2025 exhibition “…ing: Sceneries Without Sovereignty” gestures towards the ways in which gallery-art can go beyond the white cube space, subverting dominant political and cultural narratives of sovereignty, by laying bare the grotesque, corporeal body-politic of systemic oppression.

___

We cast these stray musings and renegade ideas before you, the way the city casts petals of copper-pod and amaltash on pre-dawn streets. We spread before you these notes snatched from the silent melody of our vaulting delight. Walk with us, dear reader. tread softly.