“The earth calls out, ‘Tell me Raja, why are you leaving me? You will never find such love in the city as you have found in your village!’”

— Jangarh Singh Shyam, quoted in Mark Tully, No Full Stops in India (1992)

In a painting titled Young Boy Playing the Flute in the Forest, a dark-haired youth sits beside a tree in a pasture, eyes lowered in concentration – eyes that look like silhouettes of birds flying into the horizon – as he plays the instrument. Birds also roost on the branches above him, a snake curls from behind the tree, and cattle graze nearby, all patterned with dotted stripes. The vivid, undulating composition shimmers with movement; its flattened perspective brings human and non-human forms together on a shared, non-hierarchical plane. Created in 1992, the work is, as Jyotindra Jain has speculated, perhaps Jangarh Singh Shyam’s only self-portrait. In A Conjuror’s Archive, Jain recalls the artist describing how, as a teenager, he would play his flute while tending cattle in Patangarh. “In all probability,” writes Jain, “this is the only painting in which Shyam’s self-image charts out a place from where to speak.”

This tantalising first-person glimpse is rare — remarkable even — given Shyam’s stature in 20th-century Indian art. Belonging to the Pardhan-Gond community of central India, he arrived at Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal, as a nineteen-year-old at the beginning of the 1980s to work with the artist Jagdish Swaminathan. Over the next two decades, he made paintings, etchings, prints and drawings that drew on adivasi mythologies and imaginaries to develop an entirely original and distinct visual vocabulary. In doing so, he challenged existing conceptualisations of the relationship between ‘folk’ art and ‘modern’ art. His prolific career was cut tragically short in 2001 when, while on residency to create paintings for the Mithila Museum, he reportedly hanged himself in still-contested circumstances.

In writing about Shyam’s life and work, I have consciously avoided the ethnographic tendency that shadows even the most sensitive historicising of artists from adivasi communities, especially if one is relying on secondary and tertiary sources. The more I researched, the more I realised how elusive his own voice remains. There is much commentary about Shyam, but very little by him. Jangarh Singh Shyam the artist and thinker remains a mediated presence, always incarnated in other people’s words. I have ‘listened’ to those citations and footnotes in an attempt to harmonise the various “voices” that form a picture of the artist; a picture pieced together from his rare interviews, as well as conversations cited by interlocutors. This exercise manifested as a series of notes towards a method: of listening as a way to think about a decolonial, de-Brahminical creative and critical writing of testimony.

Even the most familiar stories about Shyam contain errors that his own words quietly correct. In a 1992 interview with BBC journalist Mark Tully, he disputed the now-canonical tale of his “discovery.” Swaminathan’s team, Tully recounts, told of finding Shyam “breaking stones by the roadside.” Shyam corrected him:

“I did work on the roads. I carried baskets of mud on my head and dug mud to fill other people’s baskets, but I never broke stones.”

A small clarification, perhaps — yet one that resists the narrative of abjection and redemption that often frames Indigenous artists within institutional modernism. Through that refusal, he reclaims the narration of his own story.

In another interview from 1985, with the artist Yusuf, he admits to liking chatak rang:

“Bright colours — the good ones — are what I like,” he said. “When I work more with these, the paintings that result give me satisfaction.”

Yusuf follows up to ask if when he moved to Bhopal, he had any difficulty using these new pigments, Shyam shares that “working with them [good, bright colours] helped me make better paintings. In the village, the colours available were limited, and the paintings were more muted.”

We can begin to surmise that apart from the dotted dashes that are the well- analysed alphabet of his grammar, colour was very important to his practice. The intuitive, non-naturalistic use of chatak rang animated his figures just as much as the stipples of paint and irradiating lines of pen and ink. Shyam’s investment in colour is most apparent in his printmaking experiments wherein he devised a single-screen colour-blocked process to make serigraphs. Jain cites a conversation Shyam had with him in the 1990s in which he quotes him: “The first time I dipped my brush in bright poster colours in Bhopal, tremors went through my body.”

Indeed, Shyam was alert to the physical thrill of artistic practice. In 1989, he made his international debut at a show called Magiciens de la terre or Magicians of the Earth at the Centre Pompidou, Paris. In its catalogue, we find another rare first-person account in French. He says:

“I was so frightened by these gods that I thought I should try to represent them in forms that would be personal to me. I tried to crystallize fear in the form of beauty. This is how I could feel my fright in the form of raw vibrations…”

The phrase ‘raw vibrations’ brings to mind the strings of the Bana, the traditional instrument the Pardhan tribe would play, as minstrels and memory keepers for the Gonds. Shyam too played the Bana and composed songs, and perhaps a musical metaphor befits critical engagement with a bard.

Listening to Shyam reminded me of para-dubbed documentaries and newscasts. Para-dubbing is a process wherein the original audio track is overlaid with audio in another language, creating a composite of translation, delay, and dissonance; a palimpsest of soundtracks. In a similar way, the textual archive of Shyam’s life is a para-dubbed polyphony: multiple voices relaying, layering, translating, paraphrasing, ventriloquising. Through dialogic, relational and ever-shifting, often asymmetrical positionalities, a body of knowledge is generated. Within this polyphony, however, there is a grounding note.

In Gregorian polyphony, the cantus firmus is the fixed melody around which other voices move in counterpoint. It is not an ‘original’ voice in the sense of denoting authenticity, but a vibration that inaugurates and stabilises the polyphonic field. In this sense, Shyam’s scattered utterances — his interviews, conversations quoted largely verbatim, and letters — function as the cantus firmus of an art-historical composition that includes curators, critics, institutions, and his community. They are not the source but the pulse: a raw vibration sustaining the harmonics and dissonances of the many voices that speak about him. Another way of thinking about the cantus firmus in art historiography is in terms of the artworks. How can we listen to the first note through the images themselves, to the reverberations of the material and imaginative they embody?

The iconic painting of the leaping tiger on the wall of the Vidhan Bhavan (1996) of Madhya Pradesh, Shyam’s home state, is interpreted as another self-image by Gulammohammed Sheikh in his essay The Tribal World of Jangarh Singh Shyam. Regarding the tiger cadent through the dialectic of naturalistic posture, and shading and non-naturalistic patterns, Sheikh asks: “is it the self-image of the persona of a tamed savage?” It is through Sheikh’s attunement to Shyam’s visual grammar that his articulation of a reflexive, modernist sensibility (as opposed to the primitivist stereotype of Indigenous mark-making) is ‘audible’.

We might also connect the cantus firmus to the idea of an ‘artist-centric history’. Rex Butler describes this as “history, which would be more about the life experiences of certain groups of artists rather than retrospective justification of what has largely already entered an art museum….the idea of reversing the poles of our art history and seeing it from the point of view of the practitioners at the beginning rather than the art historians at the other end.” The artist-centric polyphony’s overlaps, pluralities and contradictions are held together by the artist’s cantus firmus, as both testimony and oeuvre.

On its own it can perform a kind of self-disclosure only possible as a direct report. There is an excellent example of the kind of revelation that is very difficult to paraphrase and paradub without that plangent first note. As we saw earlier, the Magiciens de la terre catalogue furnishes deep and poignant insight into Shyam’s background and creative process: the forest, and the fear of gods that inspired him to paint but then also this incredible, haunting line —

“for me art and life are continuous silences”.

Jain’s reading of Shyam’s self-portrait as a ‘place from where to speak’ is reminiscent of the scholar Walter Mignolo’s concept of ‘a locus of enunciation’, “constituted at the intersection of epistemology and the politics of location”. The concept, emerging from Mignolo’s study of the colonisation of Latin America and Amerindia, refers to the creative and critical navigation of new spaces of being and thinking that emerge due to colonisation, of a literal subject-position speaking for itself. In this sense, the self-portrait as a site of knowledge is an intriguing proposition.

Jain points out a paradox: “the place from where he spoke was not the actual world left behind, but the world he redeemed and recreated in his paintings”. But, following Mignolo’s point about knowledge and place, the world he left behind and the one he redeemed are in fact co-constitutive, a result of historical, political and economic processes of the long 20th century and the Indian state’s vexed relationship with subaltern communities (of which Bharat Bhavan too is an example).

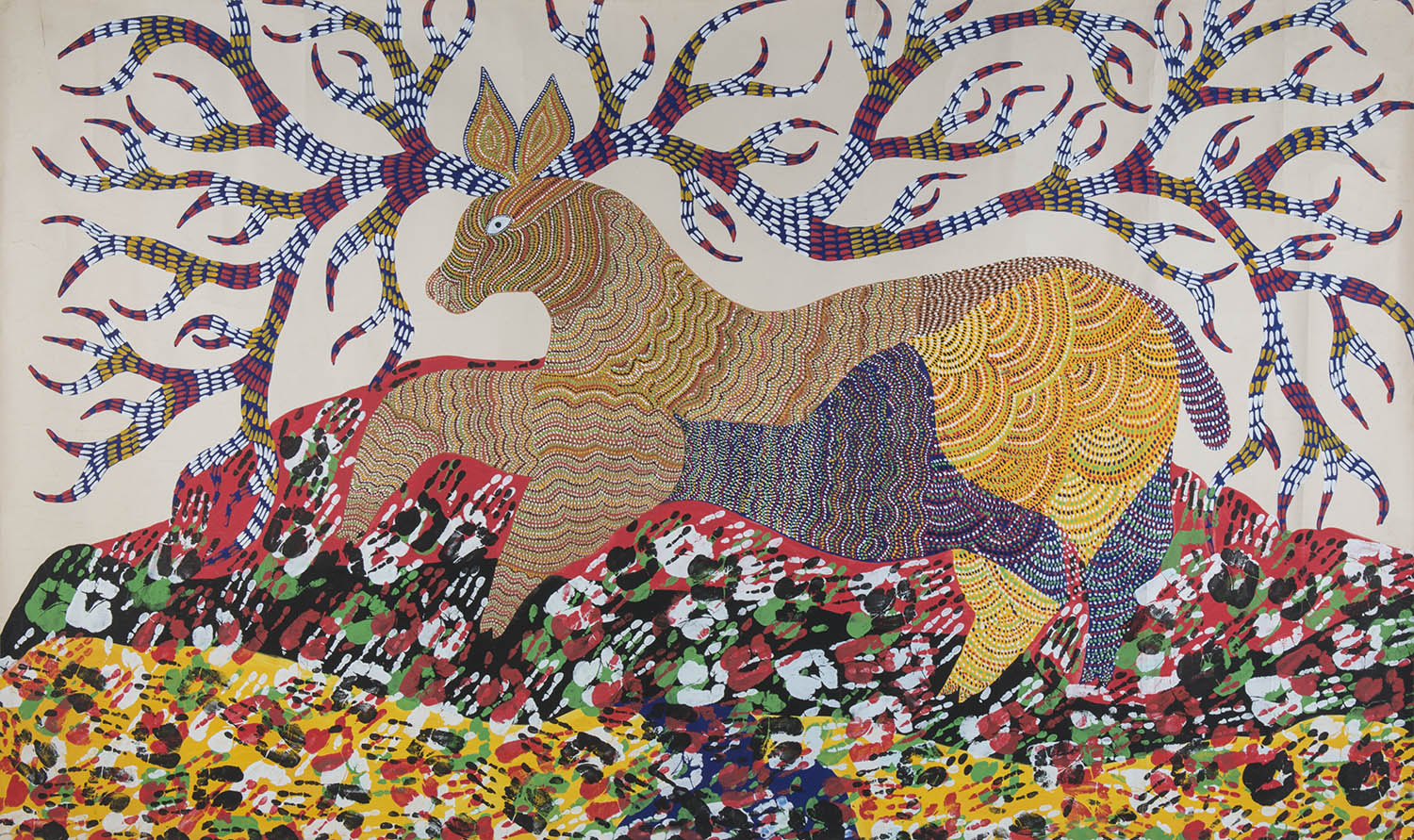

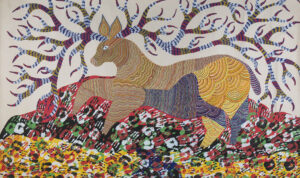

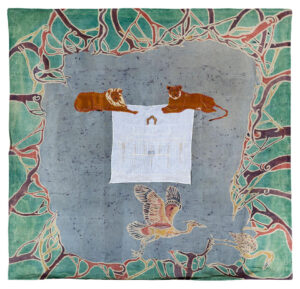

Consider his magnificent barasinghas or swamp deer with tree branches for antlers, perhaps among the most widely recognised of Shyam’s subjects in the mainstream. In one work from the mid-1980s, amidst the dramatic, almost-sentient antlers, the animal’s perky ears make themselves visible, the dot-stripe patchwork of the deer’s toy-like body propelling it through a landscape resembling batik print. Since representations of flora and fauna are easily assimilable into existing frames for viewing art by ‘forest-dwelling’ adivasi artists, it is easy to assume Shyam referenced the barasinghas of his boyhood. On the contrary, it emerged through conversation with his cousin Anand Shyam years after his demise that Shyam did not grow up seeing these animals, encountering them only as an adult at the Kanha National Sanctuary during an artists’ camp after he had joined Bharat Bhavan.

Shyam embodied many complex and aporistic contradictions at the heart of the discourse around modernism, postcoloniality and indigenism in independent India. He not only seeded an original style in his practice but cultivated an entire school of painting through a visual language that is strikingly recognisable in the mainstream art world and afar. Yet both he and his practice remain something of an enigma. The reasons for his precarious position within the dominant narratives of post-independence Indian art are multifarious, the prominent one being his somewhat unprecedented status as an Adivasi artist whose work outrightly defied or at least troubled existing schemas unable to reconcile subaltern subjectivities with modern/ist self-consciousness.

In his interview, Tully asks Shyam: ‘Surely your art has changed since you went to the city?’ “Jangarh thought for a moment and then said, ‘Well, it’s cleaner.’ ‘What does that mean? That the lines are clearer, that it’s easier to understand?’ I asked. Iyer [an artist disciple of J Swaminathan], the ‘modern’ artist, laughed. ‘No. He means that there are no longer any splodges on the paper.’ ‘That’s right,’ said Jangarh, apparently not in the least offended.”

No modern artist of caste privilege (in the sense that tribes are categorically not castes) would ever have his words and ideas be disseminated in third person to the extent that Shyam experienced. He was unaffected by this, and he never took offence. This speaks to Shyam’s practical deftness in navigating a structurally lopsided system of meaning-making and self-fashioning, even as he steered clear of maudlin sentiment.

The desire to listen for the cantus firmus is not coextensive with romanticising the ‘authentic’ voice. On the contrary, it is a move towards finding resonance within the inevitability and productivity of the polyphony that makes the ground note so valuable – not as a pure sound but as one that stabilises the chorus.