Manava dehavu moole mamsada tadike,

Manava moole mamsada tadike

Idara melide togalina hodike

Tumbide olage kaamaadi bayake…

ಮಾನವ ದೇಹವು ಮೂಳೆ ಮಾಂಸದ ತಡಿಕೆ

ಮಾನವ ಮೂಳೆ ಮಾಂಸದ ತಡಿಕೆ

ಇದರ ಮೇಲಿದೆ ತೊಗಲಿನ ಹೊದಿಕೆ

ತುಂಬಿದೆ ಒಳಗೆ ಕಾಮಾದಿ ಬಯಕೆ

The human body is a lattice of bones.

The human body is a cage of flesh.

Over it is a covering of skin.

Inside, it’s filled with sensuous desires…

These lines from the 1974 Kannada movie Bhakta Kumbara (Devoted Potter), featuring Dr. Rajkumar, has stayed with me from my childhood. It is a vivid description of the ephemeral nature of the body. For a long time, I understood this premise at a purely intellectual level. My mother passed away towards the end of 2017. Her body was cremated in a wood fire pyre in accordance with Brahmin rituals. On the day after the cremation, we had to collect the ashes from the cremation ground and immerse it in River Cauvery. When my brothers and I went to collect the ashes, we saw that the corporeal body which we had seen a day before had become a pile of ash, still warm with embers. The priest, who was attending to us, gave instructions to collect bone pieces from different parts of the body, and deposit them in an earthen pot, which in itself was a metaphor for the human body. Surprisingly these bone pieces were fully intact. We started picking up pieces of bones starting from the feet all the way up to the fractured skull which had exploded due to heat. Being an atheist, more than the Brahminical ritual, the first-hand experience of seeing my loved mother as a pile of ash, shrunken and unrecognizable hit me hard. It was an intense visceral moment which made me realise the ephemeral nature of the body – more than any book or sermon would do. As we proceeded to Sreerangapattana, I held the earthen pot on my lap, teary eyed and reflecting. That three-hour long journey to the Cauvery Sangama, and later breaking the pot, throwing it away, and dispersing the ashes in the river, was so powerful that it left an indelible mark on my being. Few years later the same ritual was repeated as my father and younger brother passed away in 2021 and 2022. In the months and years after these intense experiences I made no conscious effort to make art from them. But the effect of these experiences was profound, and it started to seep into several works on its own. This unconscious manifestation transformed my work, and changed me as a person.

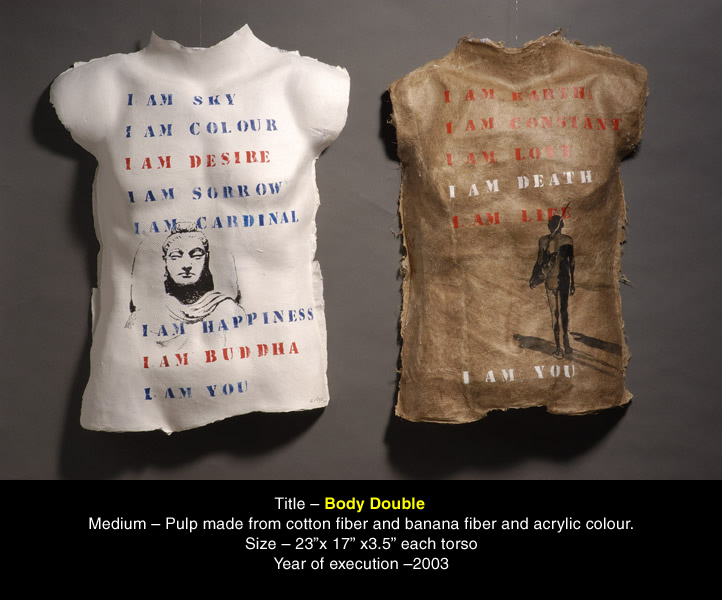

I have worked with paper for nearly 27 years now. It was a material I instinctively understood as fragile, yet capable of immense resilience, much like the human body. This early curiosity marked the beginning of a lifelong exploration into how paper could not only hold the imprints of touch and memory, but could, in fact, become a body of its own. My first attempts to articulate this idea were in works where I experimented with casting cotton fibre pulp. This process felt less like traditional sculpture, and more like a physical exchange resulting in the creation of torso and head forms, with colour or text on them. The pulped fibre was pliable, responsive to every contour and pressure. When I cast it against a mould, it registered the subtle texture and the nuances of the form, echoing the delicate, imperfect memory of moulds. The resulting forms were not pristine or perfect, but they invoked the body. They were, in essence, records of a brief, intimate interaction between mould and the form.

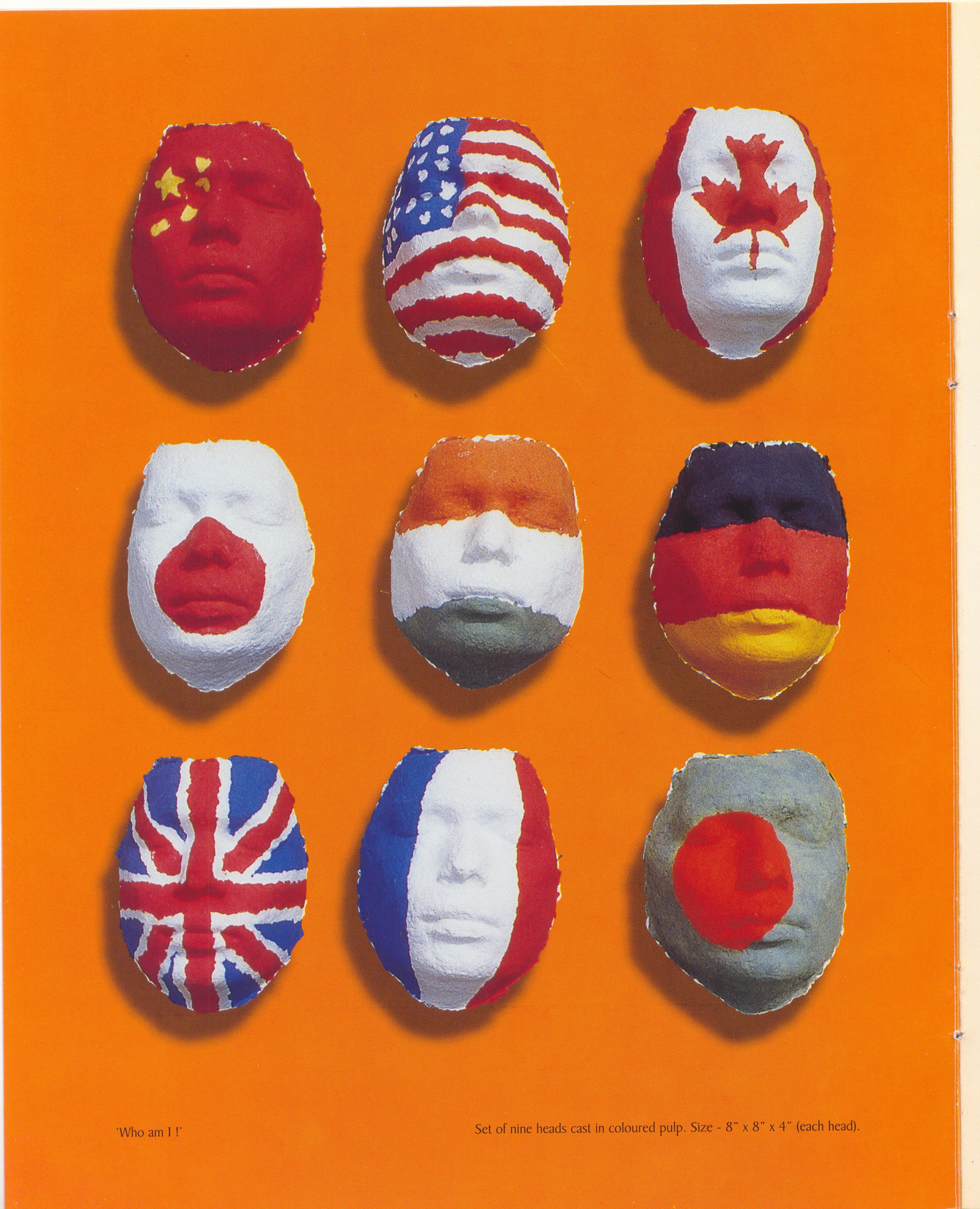

Looking at my practice in hindsight, in the light of this life-changing experience of losing loved ones, I can surmise why even though I have used the image of the body from as early as 2001, many works felt robust and solid without a hint of vulnerability at a sensory level. I have used the moulded impression of my own head like a memento mori, in works like ‘Who am I?’ (2001-02) or a later iteration of the same work where my face is covered with stars and astral bodies. In works like the cast heads of “Who am I?” (2001–02) and the torsos of “Body Double” (2003) the forms are sturdy but the works raise philosophical questions.

I escaped the predicament of the image being sturdy but the content suggesting vulnerability briefly in one work, ‘Good, Better, Best’ (2006), where I somehow was able to elicit the feeling of translucent membrane, fragility and tactile imprints of trauma, with bullet marks penetrating the torso. But this “vulnerability” soon disappeared- and it stayed that way for several years after that. In between there were attempts to dilute the solidity of the torso by puncturing or cutting it. It partially appeared in the first version of ‘Ustopic Bodies’ which I had shown in the ‘Hong Kong Biennale of paper works, where torsos were dissected and a counter point of organic growth was painted on that.

In 2022 I was at the Unnati Artist Residency in Nepal, where I got pulp from Lokta paper makers and created sculptural forms. It is possible that the time spent there in contemplation and reflection, planted some seeds of thought for a change. Frequenting Buddhist sites, museums and monasteries must also have added to this. The frequent exchanges with artist friends M. Pravat, Pratul Das, and Manish Pushkale, sometimes into the wee hours of the morning, were instrumental to this churning. In fact, one of the works produced in that residency was a sculptural form titled ‘Seed’. That work had a suggestion of a rotten seed, losing its form but still decipherable. Unknowingly I had anticipated the changes that were about to come.

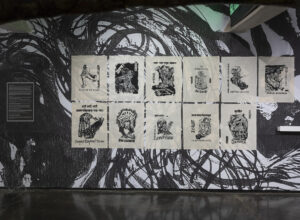

The work that came just after I returned from Nepal and after the demise of my younger brother ‘Kaya- O Brother’, holds proof that something was cooking.

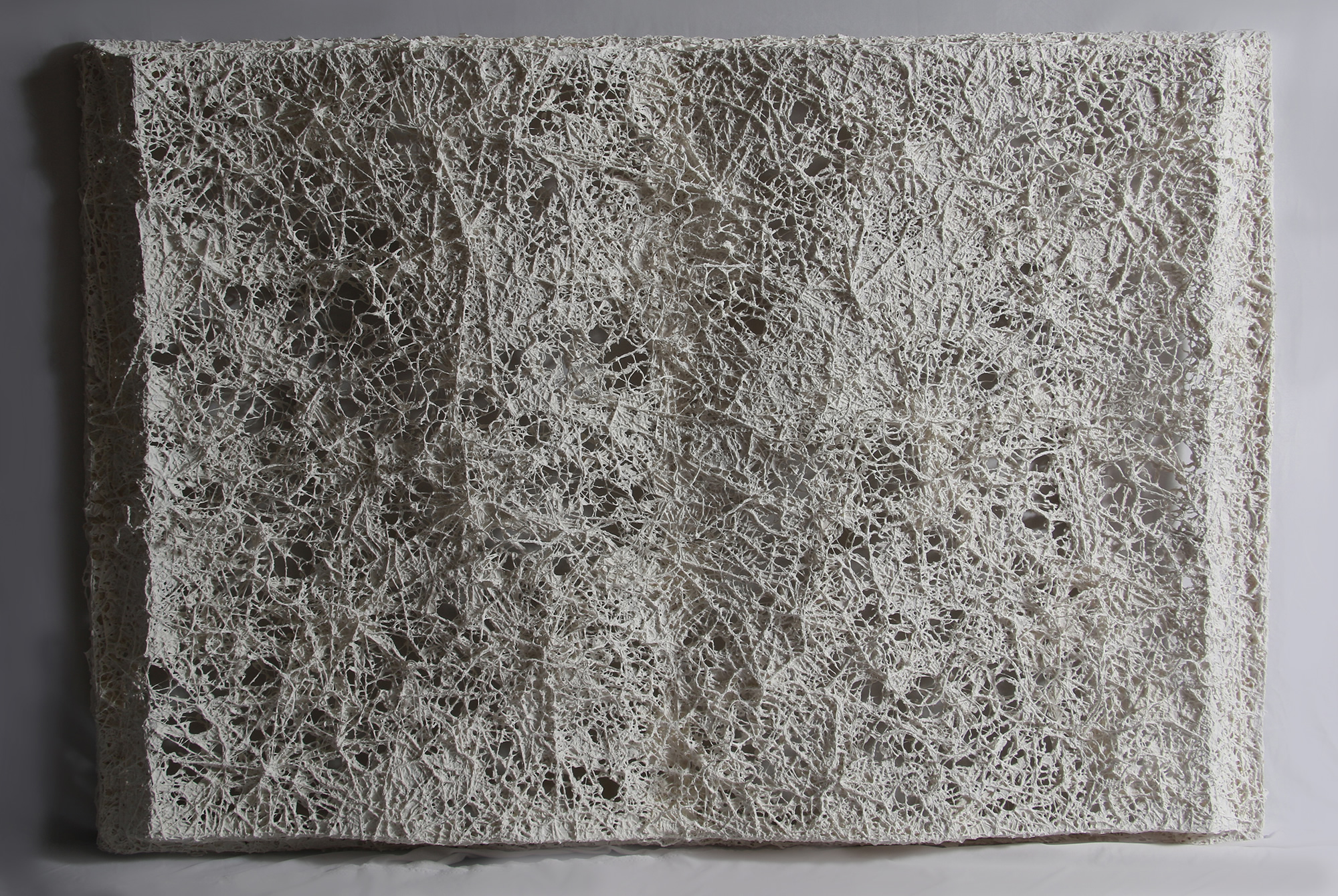

I was trying to do something different in pulp painting technique for years. But I was not getting the right kind of viscosity to bring out the pulp through the nozzle. All of a sudden, I got it right serendipitously while I was trying to help a student in a workshop, I found the correct viscosity to achieve pulp painting. It is in these pulp painted works that I inadvertently achieved the sense of vulnerability in paper.

That one insight, that paper, in its rawest form, could be a substitute skin or a membrane, changed my approach and I fully realised paper’s transformative potential. During this period paper was no longer just a surface; it had become the body itself—porous, vulnerable, and perishable—a perfect vessel for the complexities of human existence. This was not preplanned to say the least. It was almost a month or so into the phase of pulp painting that I realised the stark difference between my earlier works and the present series, where susceptibility, materiality and tactility of paper became the primary characters of my language.

As my work progressed, I began to see paper as a dual entity: both a physical body, and a carrier of more abstract concepts like language, memory, and image. Each stain, each mark, was a story; a residue of a moment or an emotion. This technique allowed me to bridge the gap between the material object and its more intimate, psychological meaning. I saw how the paper, like a person, could be marked by experience, its surface telling a story that went far deeper than its physical form.

In works from the ‘We Don’t end at our edges’ set – as well as ‘Liminal Membrane’ and “Visceral paths” – I found something I was longing for many years, to bring a sense of vulnerability into these body forms. It was a quiet shift in my studio, as I moved from seeing paper as a mere surface to understanding it as a porous, living material.

My practice continued to evolve, expanding beyond a singular material. I began to incorporate different fibers like Hanji (Korean paper), Daphne fiber, and Lokta. With each new material, I was not simply introducing a different texture or color; I was introducing a different history. Each type of paper carried with it the unique memory and geography of its origin. Hanji, known for its resilience and longevity; Daphne fiber, with its rich, natural texture, felt connected to the mountainous regions of Nepal where it is made. In this way, paper itself became a metaphor for a body with its own lineage and ancestry, a testament to the fact that we are all products of our cultures and our pasts.

Paper, with its ability to absorb, to be torn, and to be stained, felt like the perfect metaphor for the transient human body. Just as paper soaks up ink and water, our bodies absorb the joys and sorrows of a lifetime. Just as paper can be torn, or can decay over time, even our bodies return to the earth. In these works, the paper form became a silent echo of a life lived, and a delicate and poignant tribute to what is to come.

My journey with paper has been, in many ways, my journey with the body. It began with the simple recognition of paper as a surface, and it has evolved into a deep understanding of its substance. It has taught me to see the body not as a fixed object, but as a layered, interdependent entity, always vulnerable to the passage of time, the imprint of touch, and the accumulation of memory. Through my work, paper has become a quiet testament to the resilience and fragility of life itself.